Early life

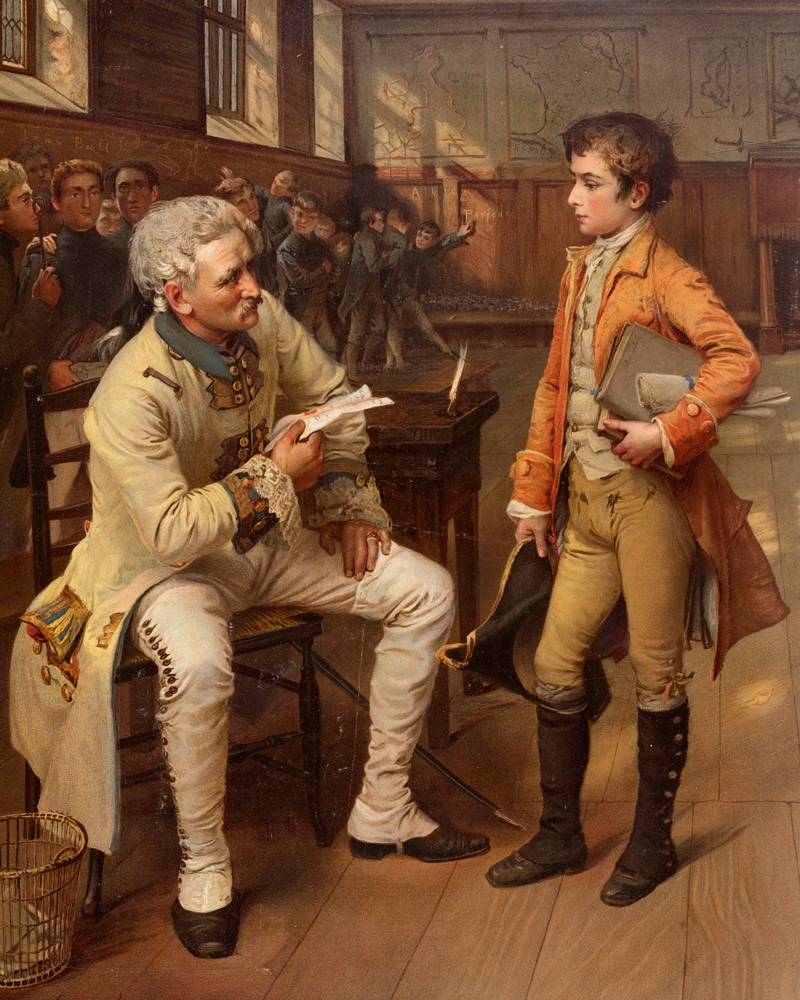

Arthur Wellesley (1769-1852) was born in Dublin in 1769 to an aristocratic Anglo-Irish family. In 1781, aged 12, he was sent to school at Eton. But his father’s death that same year threw the family into financial turmoil.

Arthur’s mother withdrew him from Eton to be schooled in Belgium and France. She saw such little promise in her son that she felt the military was the best career choice for him. He was commissioned as an ensign in the British Army in 1787.

‘I vow to God I don't know what I shall do with my awkward son Arthur. He is food for powder and nothing more.’Anne Wellesley, Wellington's mother

India

Arthur first saw action during the early years of the French Revolutionary Wars (1793-1802). In the Netherlands, he learnt valuable lessons on leadership, organisation and tactics.

In 1796, he sailed to India, where his brother Richard had been appointed Governor-General. Now a colonel, Arthur was appointed chief advisor to the Nizam of Hyderabad's army. He then led the 33rd Regiment at Malavelly and Seringapatam in 1799.

Although later derided as a ‘sepoy general’ by Napoleon, Wellesley learnt a lot in India that would prove vital in his Peninsular War campaigns. This included the importance of discipline, diplomacy with allies, intelligence gathering, manoeuvring, secure supply lines and naval support.

Arthur was promoted to major-general in 1802 during the 2nd Maratha War (1803-05). At Assaye on 23 September 1803, he won his first major victory. He later regarded this as the best battle he ever fought. Victories at Argaum and Gawlighur followed.

Arthur returned to England in 1806, where he embarked on a political career as a Tory member of parliament for Rye. He continued his political career before serving at Copenhagen in 1807.

The Peninsula

In 1808, Wellesley was made lieutenant-general and sent to Portugal, where he defeated the French at Roliça and Vimeiro. During the latter engagement, he checked the French columns with the reverse slope defence, a tactic that became his trademark.

Following the controversial Convention of Cintra (1809), he was recalled to Britain to face a court of enquiry. He was cleared of any wrongdoing and returned to the Peninsula, where he secured Oporto and drove the French from Portugal.

He pursued the enemy into Spain, winning a narrow victory at Talavera (1809), for which he was raised to the peerage. But, following the arrival of French reinforcements, he fell back into Portugal.

In 1810, the newly styled Viscount Wellington slowed the French advance at Buçaco, before halting them at the Lines of Torres Vedras. The French withdrew to Spain in March 1811.

Wellington then moved on Almeida. He defeated the French at Fuentes de Onoro in May. In January 1812, he took Ciudad Rodrigo - for which he received an earldom - and assaulted Badajoz in April.

On 22 July 1812, he won a great victory at Salamanca. This battle proved Wellington had the ability to manoeuvre and attack in the open field, and established his reputation as an offensive general. However, his subsequent failure to take Burgos (September-October 1812) forced the British to retreat once more to Portugal.

Advancing back into Spain in May 1813, Wellington destroyed the French army at Vittoria, personally leading one of the columns against the French centre. This victory earned him a field marshal's baton and was followed by the capture of San Sebastian and the advance into France.

After Napoleon's abdication in 1814, Wellington returned home a hero. He was raised to the highest rank of the peerage, becoming the Duke of Wellington.

Waterloo

He attended the Congress of Vienna to agree a peace plan for Europe. But when Napoleon returned to power in February 1815, Wellington immediately assumed command of the allied armies, overseeing German, Dutch and Belgian troops.

He joined forces with the Prussians in the Netherlands, but was taken by surprise at Quatre Bras on 16 June 1815. Two days later, Wellington faced Napoleon at Waterloo.

The Battle of Waterloo, on 18 June 1815, was fierce and bloody. But with Prussian help, Wellington emerged victorious. The battle ended French attempts to dominate Europe and secured Wellington's place in the history books.

‘Hard pounding this, gentlemen; let's see who will pound longest.’Duke of Wellington during the Battle of Waterloo — 18 June 1815

Later life

The victory at Waterloo cemented Wellington's status as a military hero. He returned to his political career and served as prime minster from 1828 to 1830, and again in 1834.

However, his strong leadership style - so effective on the battlefield - proved autocratic and contentious in Westminster. And he soon realised that leading a country was quite different to leading an army.

He oversaw Catholic Emancipation in 1829, but courted unpopularity by opposing the 1832 Reform Act.

‘The Duke of Wellington had exhausted nature and exhausted glory. His career was one un-clouded longest day.’Wellington's obituary in The Times — 1852

Wellington's brief second premiership ended when he stepped down in December 1834. But he did not completely withdraw from public life until 1846. He remained commander-in-chief of the army, a role in which he proved resistant to military reform.

Wellington died from a stroke on 14 September 1852. On his death, he was once again hailed as the hero of Waterloo. Queen Victoria even described him as 'the greatest man this country ever produced'.

He was given a state funeral in London and was laid to rest in St Paul's Cathedral, next to Britain's other military hero of the age, Lord Horatio Nelson.