Explore more from American War of Independence

American War of Independence: Key battles

11 minute read

Under siege

Following the Battles of Lexington and Concord and the outbreak of revolt across New England, the American rebels laid siege to Boston. The British position was fairly secure once reinforcements arrived at the end of May 1775. However, continually menaced by fire from the surrounding hilltops, the British decided to occupy these positions.

On 17 June, British troops were ferried across to Breed’s Hill on the Charlestown Peninsula. At the cost of more than 1,000 casualties, they defeated the revolutionaries at Bunker Hill. The order, 'Don't fire until you see the whites of their eyes!' was popularised by stories about this battle, although it's unclear who actually said it.

Boston falls

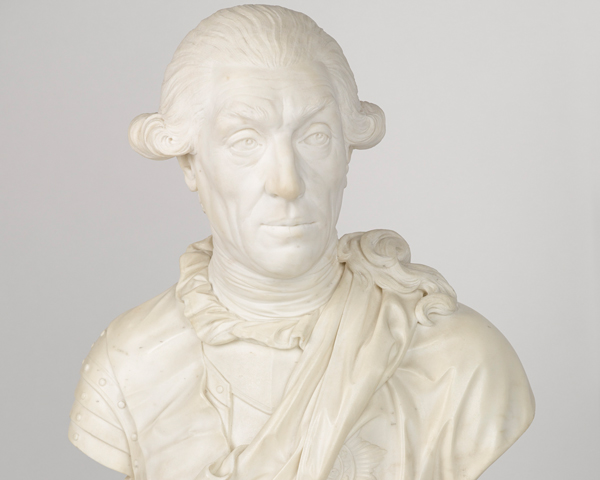

On 4 March 1776, General George Washington moved his newly raised army to Dorchester Heights and placed his artillery in position to menace Boston. Bad weather and American privateers (state-sponsored pirates) prevented supplies from reaching the city. In April, Major-General William Howe, the new British commander-in-chief, evacuated the besieged city and regrouped his forces at Halifax, Nova Scotia.

This episode demonstrates one of the main problems faced by the British. Throughout the war, they had to transport men and supplies across the Atlantic. In such circumstances, the loss of control of the sea, however temporary, could have dire consequences.

Canada

As the siege of Boston dragged on, the Americans decided to widen the war and invade Canada. Their goal was to encourage its inhabitants to join the revolution. On 16 September 1775, Brigadier-General Richard Montgomery marched north with about 1,700 militiamen, capturing Montreal on 13 November.

Moving on to Quebec City, he was joined by Colonel Benedict Arnold, who had led another force north. On 31 December 1775, they were defeated by General Guy Carleton. Montgomery was killed and Arnold wounded.

The remaining American soldiers held on outside Quebec City until the spring of 1776. They then withdrew towards Montreal.

Counter-attack

On 8 June, having received reinforcements, the British struck back at Trois-Rivieres against an American army weakened by disease. Carleton then launched his own offensive, forcing the Americans to abandon Montreal on 15 June. They were soon pushed back to Ticonderoga, from where they had started out more than a year earlier.

The Canadians had not rallied to the American cause. Even the French inhabitants remained indifferent. But Arnold's efforts in 1776 had succeeded in delaying a full-scale British offensive.

New York captured

In June 1776, a reinforced Howe left Halifax and entered New York Bay. He established a camp on Staten Island and consolidated his forces. On 22 August, around 22,000 British troops landed on Long Island.

In the battle that followed on 25 August, Washington's soldiers were eventually driven back and evacuated to Manhattan. On 15 September 1776, Howe landed 12,000 troops on Lower Manhattan and entered New York City.

Rebel disaffection

After fighting battles at Harlem Heights on 16 September, White Plains on 28 October and Fort Washington on 16 November, Howe spent the winter in New York.

Although he had missed several opportunities to crush Washington's force, Howe had killed or captured over 6,000 soldiers. Many more had returned to their homes, and disaffection with the rebel cause was spreading.

Hearts and minds

Howe sympathised with the rebels' grievances and was reluctant to use maximum force to end the rising. Many on the British side still hoped to win over neutral Americans and moderate Patriots.

Harsh measures might have quickly ended the revolt. But they would also have alienated the colonial population and turned public opinion at home against the government.

Trenton

Pursued by General Sir Charles Cornwallis, Washington withdrew across the River Delaware into Pennsylvania in early December 1776. Although his force was severely weakened, he re-grouped and crossed the ice-covered Delaware with 3,000 men on Christmas night.

His men defeated a force of Hessians (German troops in British pay) at Trenton on 26 December, taking over 1,000 prisoners. Many of the Hessians were still recovering from their Christmas Day celebrations. Only four Americans were wounded.

Princeton

The victory at Trenton gave the Patriots a new confidence. It proved that Americans could defeat the Crown's regular soldiers. It also increased enlistment in the Continental Army. Cornwallis marched to retake Trenton, but was defeated at Princeton on 3 January 1777.

After looting the British supplies, the Continental Army marched north to winter in Morristown, New Jersey. Cornwallis abandoned many of his posts in New Jersey and retreated to New Brunswick.

Philadelphia

In 1777, Howe advanced on Philadelphia, the home of the American government. He landed 15,000 troops in late August at the northern end of Chesapeake Bay, before defeating Washington at Brandywine Creek on 11 September. British losses were 550 killed and wounded, American losses around 1,000. The Patriots subsequently abandoned Philadelphia.

Valley Forge

Washington re-grouped. He attacked the British encampment at Germantown on 4 October 1777, but was repulsed after one of his four columns lost its bearings in the fog and smoke.

Next, he repelled the British attacks at White Marsh in December. Howe returned to Philadelphia without engaging Washington in a decisive conflict.

With the British back in Philadelphia, Washington was able to march his troops to winter quarters at Valley Forge. Here, an estimated 2,500 out of 10,000 men died from disease and lack of supplies over the winter. Washington also spent this period drilling and training his men.

Burgoyne’s advance

Meanwhile, Lieutenant-General Sir John Burgoyne was attempting to isolate and destroy American forces in New England by advancing down the Lake Champlain route from Canada. He marched south from Montreal with 10,000 men. But the need to garrison Ticonderoga (captured in July) and defeats at Bennington on 16 August and Freeman's Farm on 19 September 1777 reduced his force.

Burgoyne's army was now reduced to about 6,000 men. Despite these setbacks, he pushed on towards Albany, New York. He was soon bottled up by a large American army commanded by Major-General Horatio Gates.

Surrender at Saratoga

With supplies running low and no sign of reinforcements, Burgoyne attempted to escape the trap by attacking the American position at Bemis Heights on 7 October. The British troops were repelled and Burgoyne lost several of his most effective officers, including Brigadier Simon Fraser.

Burgoyne surrendered his remaining men at Saratoga on 17 October 1777. Of the 10,000 British and German soldiers who had marched from Canada, only 3,500 were fit for duty at the surrender. This defeat had far-reaching consequences as it helped persuade the French to enter the war on the American side.

Monmouth

Despite the disaster at Saratoga, the British fought on. They were convinced that many areas of America were potentially Loyalist and only needed Britain's protection to rise up against the Patriots.

Howe's successor as commander, General Sir Henry Clinton, evacuated Philadelphia. He concentrated his forces around New York, which was now under serious threat from a recently arrived French naval force.

General Washington followed Clinton's withdrawal and engaged his force at Monmouth, New Jersey on 28 June 1778. The battle was a stalemate and the British were able to continue their march eastwards. But it showed that the Patriot army was becoming a formidable force under its French and Prussian instructors, and was now able to engage British regulars on an equal footing.

Charleston captured

In December 1778, the British invaded the southern colonies. They hoped to regain control by recruiting Loyalists there. This operation would also keep the Royal Navy closer to the Caribbean, where the British needed to defend their possessions against the French.

The war in the south witnessed savage fighting. Atrocities were committed by both sides. On 29 December 1778, the British captured Savannah in Georgia. On 12 May 1780, Charleston, the biggest city and port in the south, was taken after a short siege. The loss of the city and its 5,000 troops was a serious blow to the Americans.

Camden

Next, the British routed a newly raised American army at Camden, South Carolina on 16 August 1780. American casualties were 1,000 killed, wounded or captured, with another 132 missing, including the French general Baron De Kalb. The Americans also lost most of their supplies and artillery. British losses were 313 killed and wounded, and 64 missing.

Yorktown

Cornwallis advanced into Virginia, but ran into two fresh American armies. He won a series of minor victories against them, but short of supplies, he was forced to withdraw to the port of Yorktown. Here, he hoped he would be supported by the Royal Navy.

Cornwallis was soon besieged by a Franco-American force of 17,000 men. The arrival of a French fleet in Chesapeake Bay in September 1781 sealed his fate. With no prospect of relief, and under fire from land and sea, Cornwallis asked for terms. On 19 October 1781, he surrendered.

Peace

Yorktown was not the end of the war. The British still had 30,000 troops in North America and still occupied New York, Charleston and Savannah. Fighting continued on land and at sea. But the defeat finally convinced the British that, faced with their world-wide commitments, the war in America was unwinnable.

Peace negotiations opened in April 1782. They concluded with the Treaty of Paris in September 1783, when Britain recognised the independence of the United States.

The British Army had performed relatively well on the battlefield and had shown an ability to adapt their tactics to suit the North American terrain. But the problems of logistics were insurmountable, and the entry of France and Spain into the war on the side of the colonists negated British naval dominance and proved decisive.

A global conflict

The French had signed the Treaty of Alliance with the colonists in February 1778, hoping to avenge their defeats to the British during the Seven Years War (1756-63). Their entry into the conflict meant that British naval superiority, which had proved vital in the early part of the war, was now contested, both in North America and the Caribbean. French soldiers and supplies were also crucial to the Patriot cause on land.

The Spanish, eager to recover the territories of Florida, Gibraltar and Minorca from the British, entered the war as an ally of France in June 1779. They also had their sights on the British outposts on the River Mississippi.

This meant that British resources and soldiers could no longer be concentrated on North America alone, but had to be deployed around the globe. The Spanish and French were successful at Pensacola in Florida in May 1781, and Minorca, which they captured on 5 February 1782. Both territories were retained after the war.

Gibraltar

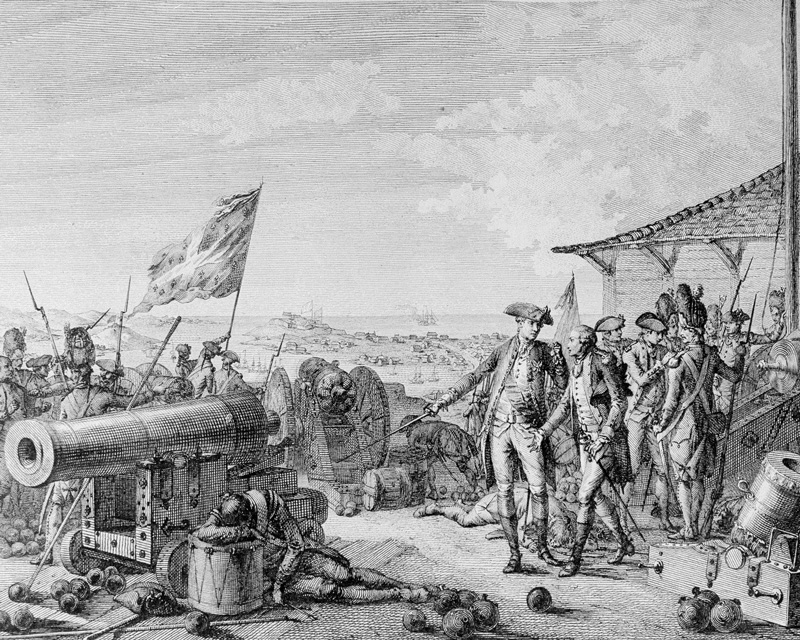

On 24 June 1779, the Spanish besieged the British garrison on the Rock of Gibraltar. The siege reached a crisis point in September 1782, when a combined Franco-Spanish assault, involving 100,000 men, 48 ships and 450 cannon, attacked General George Eliott's garrison.

The Rock was bombarded by a number of specially designed floating batteries. But in a daring and dangerous move, British gunners fired back with red-hot shot, setting many of the batteries on fire and causing some to explode.

The enemy fleet retreated and the garrison was able to keep up its resistance until the end of hostilities in 1783.

The Caribbean

The war in the West Indies was marked by naval raiding and skirmishing. The French succeeded in capturing several British possessions in the Lesser Antilles, including Saint Lucia (1778), Grenada (1779) and Tobago (1781).

But Admiral Rodney's naval victory at the Battle of the Saintes in April 1782 ended Franco-Spanish hopes of taking Jamaica. It also safeguarded the vital Caribbean trade and did much to restore flagging British morale.

India

French entry into the war also renewed the old Franco-British rivalry on the Indian subcontinent. A British-Indian force struck first, capturing Pondicherry on 18 October 1778 and Mahe, on the Malabar coast, the following year.

The ruler of the state of Mysore, Hyder Ali, sided with the French following the annexation of lands belonging to one of his dependents. His 90,000-strong army defeated a British-Indian force at Parambakum on 10 September 1780.

Sir Eyre Coote was then sent against Hyder Ali with a larger force. He defeated him at Porto Novo on 1 July and Pollilore on 27 August 1781. Coote was again victorious at Sholinghur on 27 September 1781. But the war dragged on with neither side able to claim a decisive victory.