State of affairs

On 15 August 1945, British soldiers and civilians across the world celebrated Victory over Japan Day (VJ Day). Earlier that month, the United States had dropped two atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, causing death and destruction on an unprecedented scale. The advent of nuclear warfare complicated any ambition of building a sustainable peace.

In official accounts, VJ Day stands as the final act of the Second World War. But today, some historians challenge the idea that 1945 marks a conclusive end point to the conflict. After the defeat of Italy, Germany and Japan, local and regional conflicts continued to rage across the globe for years to come – in many cases involving the soldiers of Britain and its empire.

Across eastern Asia, the rapid collapse of the Japanese Empire created a power vacuum. British and Indian troops were soon tasked with reasserting control over Britain’s own imperial holdings, including Hong Kong and Singapore.

British and Indian Army soldiers also became entangled in colonial wars in French Indochina (modern-day Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos) and the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia), where independence movements seized their chance to overthrow French and Dutch colonial rule respectively. While victory over Japan was a moment of unquestionable triumph, the fighting was not yet finished for a considerable number of soldiers.

In Europe too, the task still facing the British Army was considerable. The Potsdam Agreement formalised plans for a four-power military government of Germany. Britain’s soldiers were tasked with implementing the ‘Four Ds’ of denazification, demilitarisation, de-industrialisation and democratisation – a bold and ambitious set of objectives.

The agreement also outlined major territorial changes on the continent, including an expansion of Poland’s borders westwards and a consequent population transfer of the Germans who were living in these regions. This would become one of the largest refugee movements in history, with millions of people moving to areas of Germany under the control of Allied troops.

Meanwhile, the increasing influence of the Soviet Union over vast swathes of Eastern Europe - especially Poland - was a cause of growing concern to the Western powers.

Attlee, Truman and Stalin at Potsdam

Following the Labour Party’s victory in the UK general election, Prime Minister Clement Attlee returned to Berlin as head of the British delegation to the Potsdam Conference.

Of the ‘Big Three’ leaders who had attended the talks at Yalta six months earlier, Soviet premier Joseph Stalin was the only one remaining.

At Potsdam, the Allies finalised their plans for the postwar peace.

‘We had an amazing party given by the Russians to some British & Americans. It was held in the Conference Palace on the night of the last conference. They had a vast banquet in the banquet hall – caviar, vodka (which I don’t like!) etc & music was playing in the actual conference room. Some of us danced in the adjoining room, (which was Stalin’s private one) so we were sitting out from dancing round the conference table on the last day of the conference – I sat in Stalin’s chair!’Junior Commander Margot Marshall, Auxiliary Territorial Service, in a letter sent to her grandma from Berlin, Germany

Potsdam Agreement signed

1 August 1945

The Potsdam Agreement set out a comprehensive plan for the peace in postwar Europe. It outlined the objectives of the Allied military occupation of Germany, abbreviated as the ‘Four Ds’ of denazification, demilitarisation, de-industrialisation and democratisation.

The agreement also decreed major territorial changes. Former German territory was to be ceded to a new, enlarged Poland. This required a westward population transfer of the Germans living in this region.

In addition, the Allies agreed to establish a Council of Foreign Ministers comprised of representatives from Britain, the USA, the Soviet Union, France and China. This body would continue the work of drawing up peace treaties for Axis nations in Europe (Italy, Romania, Bulgaria, Hungary and Finland) and resolving outstanding territorial disputes.

The Allied occupation of Germany

The Potsdam Agreement formally initiated the military government of Germany. France became one of the four occupying powers, alongside Britain, the USA and the Soviet Union. A small number of troops from Luxembourg, Norway, Poland and Belgium would also take part in the occupation of Germany.

The occupiers established the Allied Control Council in Berlin, a proxy government responsible for matters affecting Germany as a whole and where decisions required unanimous assent. But each of the four powers was to govern independently within its own occupation zone, wielding total control over almost all areas of state and society.

Berlin, although located deep inside the Soviet zone, was similarly split between the four occupiers, with each sector of the city ruled independently.

The Control Commission for Germany (British Element) was a civilian component of the British military government, working alongside the British Army of the Rhine (BAOR).

‘In accordance with the Agreement on Control Machinery in Germany, supreme authority in Germany is exercised, on instructions from their respective Governments, by the Commanders-in-Chief of the armed forces of the United States of America, the United Kingdom, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, and the French Republic, each in his own zone of occupation, and also jointly, in matters affecting Germany as a whole, in their capacity as members of the Control Council.’Potsdam Agreement, Cecilienhof Palace — 1 August 1945

The ‘Four Ds’ in occupied Germany

At Potsdam, the occupiers proclaimed their intention to:

- ‘denazify’ German society, including through war crimes trials;

- ‘demilitarise’ their conquered foe;

- ‘de-industrialise’ the German economy to eradicate the country’s ability to wage war; and

- ‘democratise’ the institutions of German state and society.

These became known as the ‘Four Ds’.

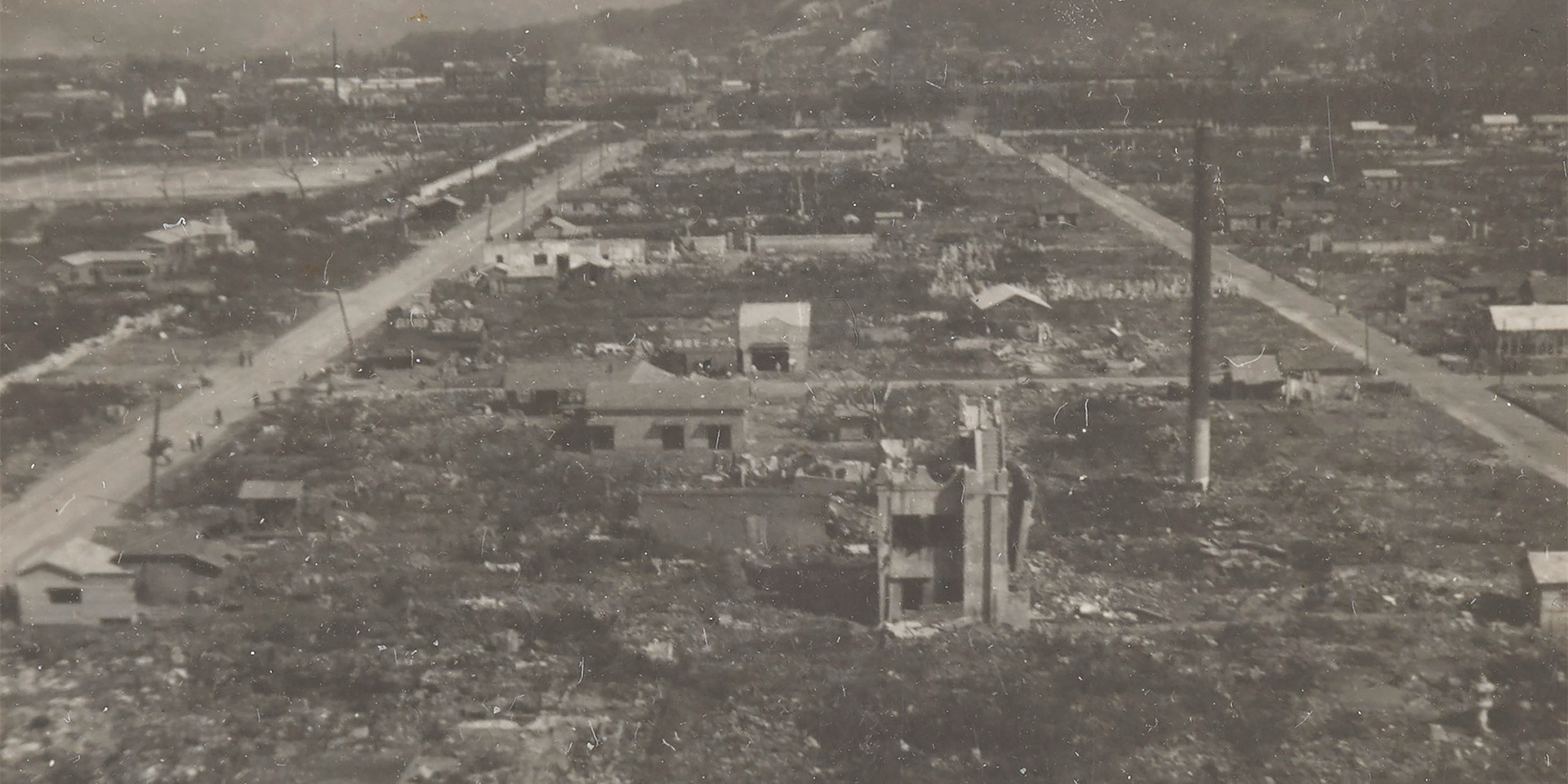

Bombing of Hiroshima

6 August 1945

On 6 August, the United States dropped an atomic bomb on the Japanese city of Hiroshima. It was the first operational use of a nuclear weapon in history.

The explosion caused an unparallelled amount of damage from a single strike: the initial blast and firestorm - coupled with nuclear radiation - killed at least 90,000 people. (Some historians believe the figure was closer to 160,000.)

Royal Engineer Arthur Lowden took this photograph of the devastated ruins in Hiroshima some months later.

‘I had finished breakfast and was getting ready to go to the newspaper [office] when it happened. There was a flash from the indoor wires as if lightning had struck. I didn’t hear any sound, how shall I say, the world around me turned bright white. And I was momentarily blinded as if a magnesium light had lit up in front of my eyes. Immediately after that, the blast came. I was bare from the waist up, and the blast was so intense, it felt like hundreds of needles were stabbing me all at once.’Yoshito Matsushige, Midori-cho, Hiroshima (1.7km from the epicentre) — 6 August 1945

Nuremberg Charter

On 8 August, the Allies issues the Nuremberg Charter which set down the laws and procedures for bringing Axis war criminals to justice. It designated ‘Crimes Against Peace’, ‘War Crimes’ and ‘Crimes Against Humanity’ as within the jurisdiction of future tribunals.

Soviet Union enters war against Japan

On 9 August, a day after the Soviet Union’s declaration of war on Japan, the Soviet Red Army invaded Japanese-occupied areas of north-east China. This was in accordance with the agreements made at Yalta. It also marked a significant milestone in the war between China and Japan that had started in 1931.

The Soviet Union’s involvement in East Asia would have significant implications for the future of the region following the impending defeat of Japan.

Bombing of Nagasaki

9 August 1945

The USA dropped a second nuclear bomb on mainland Japan on 9 August. This time, the target was the city of Nagasaki. Again, the result was overwhelming devastation and mass death.

The following day, the Japanese government signalled its intention to accept the Allied terms of unconditional surrender.

(Image courtesy of IWM)

Signs of Surrender

On 10 August, news of Japan’s willingness to surrender spread across the world. In London's Piccadilly Circus, crowds of civilians and soldiers celebrated the news with dancing and singing.

Operation Downfall

A two-part plan to invade the Japanese mainland (codenamed Operation Downfall) was scheduled to begin on 1 November 1945 (Operation Olympic), with a secondary assault in March 1946 (Operation Coronet). British and Commonwealth forces were due to take part in the second operation.

On 10 August, official orders were sent to that effect, despite the news of Japan’s impending surrender. The British 3rd Division was earmarked for service, with soldiers set to be given 28 days' leave before setting sail for North America. As it transpired, these orders never had to be put into action.

Operation Zipper

In mid-August, armoured units of the 19th King George V's Own Lancers were transported from Burma (now Myanmar) to Madras (now Chennai) in India. This was in preparation for an invasion of Malaya (now Malaysia), codenamed Operation Zipper.

The plan was never fully executed due to the end of the war, but a small landing force did arrive at Penang in early September, where it met no resistance from the Japanese garrison.

The photograph above shows soldiers of the 25th Indian Division searching surrendered Japanese troops in the Malay capital, Kuala Lumpur.

(Image courtesy of IWM)

VJ Day

15 August 1945

The announcement of Japan’s surrender on 15 August officially marked the end of the Second World War. A day later, a ceasefire order was communicated to all Japanese forces.

News of Japan’s defeat prompted celebrations and parades across the world. In Britain, a two-day public holiday was announced. Pictured above is the official VJ Day parade in Nairobi, Kenya.

For others, including British prisoners of war (POWs) still in Japanese captivity, the surrender prompted a more muted response. After years of conflict, the principal sentiment for many war-weary British civilians and soldiers was one of relief at the prospect of peace.

On 2 September, Japanese leaders signed formal surrender papers aboard the USS 'Missouri' in Tokyo Bay. The USA marks VJ Day on this later date. In China, commemorations fall on 3 September.

‘I can hardly believe that the war is over, and yet that is the only way one can explain the behaviour of the [Japanese]. There is no factory work today… On the other hand there is no official announcement?’Diary entry of Corporal Abraham Gumburd, Middlesex Regiment, while a prisoner of war in Japan — 16 August 1945

‘There has been no organised Peace Celebration here through lack chiefly of anything to do with it. Two days’ holiday were ordered, but this meant very little as the position had not altered here... The best and quite impromptu celebration was a “Feu de joie” [rifle salute]... a pistol was fired. Then a rifle, followed by a Bren, and within minutes all the small arms in the place were being fired off into the air. Of course it was very irregular but as a spontaneous gesture it was good, and it was a very fittingly irregular mark to finish an odd campaign. Unfortunately one or two units “stood to” as they thought we were being attacked.’Captain Peter Whitfield Gallup, Royal Field Artillery, reflecting on VJ Day in Burma — 21 August 1945

Death Toll

The Second World War was the deadliest conflict in human history, with more than 60 million people of all nationalities losing their lives.

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission memorialises more than 580,000 British, Commonwealth and Empire military personnel who were killed between 1939 and 1947. This includes over 350,000 soldiers of the land forces of the Crown.

In addition, more than 67,000 British civilians lost their lives, mainly in the Blitz. And across the Empire, several million non-combatants died as a result of conflict, aerial bombing, and famine (most notably in Bengal, India).

Operation Barleycorn, Germany

After the huge upheavals and destruction of the war, there were grave fears about the ongoing availability of food and fuel in many parts of the world, including occupied Germany.

In the summer and autumn of 1945, 300,000 German POWs were released from captivity to help bring in the harvest in the British Zone as part of Operation Barleycorn.

German prisoners were also released to work in the Ruhr coal mines during Operation Coalscuttle.

August Revolution, Vietnam

In the aftermath of Japan’s defeat, national independence movements sprang up across Southeast Asia.

On 16 August, the Viet Minh - under the leadership of the Indochinese Communist Party - launched a revolution against the Empire of Japan while also rejecting a return to French colonial rule.

With covert (but short-lived) American backing, Viet Minh leader Ho Chi Minh declared the independence of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam on 2 September 1945.

As France lacked adequate military resources to respond by itself, British and Indian forces were deployed to the country to reassert French colonial control.

(Image courtesy of the National Archives of the Netherlands)

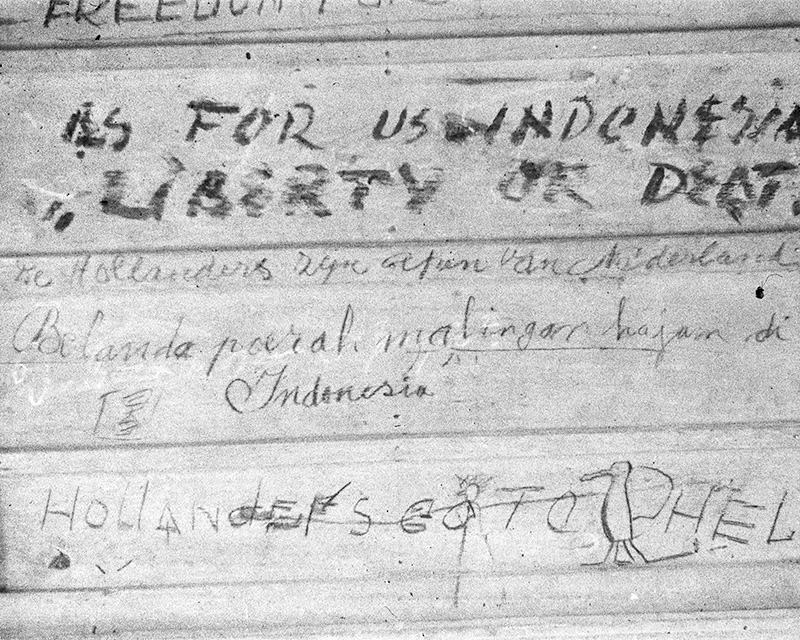

Indonesian National Revolution

The Indonesian National Revolution began on 17 August. This was a diplomatic and armed struggle against Dutch imperial rule that would last for the next four years.

Pictured above is some anti-Dutch graffiti from this period. It includes the message: ‘Belanda poerah malingan kajam di Indonesia’ (‘The Netherlands is a violent thief in Indonesia’).

With the Netherlands unable to muster a force sufficient to restore its own rule, British and Indian forces were sent to Indonesia to uphold Dutch colonial power.

Denazification in Germany

All captured German soldiers were subject to vetting as part of Allied denazification efforts.

By August 1945, over a million German POWs had proven their non-Nazi credentials to the British authorities and were released from captivity. But many thousands still remained behind barbed wire awaiting their fate, with punishments ranging from fines to execution.

At the same time, British soldiers were involved in the hunt for the most serious Nazi war criminals, many of whom had gone into hiding.

‘the forces of evil have been overthrown. But many tasks remain to be accomplished if the full blessings of the peace are to be restored to a suffering world. It is the duty of each one of us to ensure that your comrades have not died in vain, and that your own hard-won achievements are not lost to the cause of Freedom, in which you undertook them.’Special Army Order from King George VI to all British troops — 18 August 1945

World Zionist Congress

19-23 August 1945

In London, the World Zionist Congress met for the first time since 1939. In the immediate aftermath of the Holocaust, delegates demanded that a million Jews be allowed to migrate to Palestine, a British-run mandate with a majority Arab population.

Administering the peace

In the wake of victory, British Army soldiers were deployed across the world. Many still had key duties as part of military occupations or administrative responsibilities. Their work could range from radio broadcasting to supply logistics. Yet others were biding their time awaiting demobilisation.

Members of the Auxiliary Territorial Service (ATS) are pictured above relaxing on the roof of the Residence Palace in Brussels in August 1945.

‘I was appointed Director of Broadcasting at Radio Trieste, where I would have a combined staff of Italian and Jugoslav civilians... The broadcasting policy was that all news and feature programmes would be produced by the Anglo-American specialist staff in accordance with Foreign Office and State Department instructions... the broadcasting services for the Allied Garrison were supplied exclusively by the British Forces Network and the American equivalent.’Memoir of Major Archibald Yuill, Grenadier Guards, serving with the Political Warfare Executive, Trieste — August 1945

Communists take power in Eastern Europe

The Allies had agreed that free and fair elections should be held at the end of the war in Europe. But by August 1945, the Western powers (the United States, Britain, France and their allies) were increasingly concerned at what they perceived as Soviet meddling in the political affairs in the east of the continent.

The rapid rise of communist parties and their apparent intolerance of opposition in Czechoslovakia (now the Czech Republic and Slovakia), Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria and Poland would become a major point of tension between the wartime Allies in the months and years to come.

‘I turn now to the situation in Bulgaria, Rumania [sic] and Hungary. The Governments which have been set up do not, in our view, represent the majority of the people, and the impression we get from recent developments is that one kind of totalitarianism is being replaced by another. This is not what we understand by that very much overworked word "democracy”.’Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin, House of Commons, London — 20 August 1945

Lend-Lease terminated

On 20 August, US President Truman announced that the Lend-Lease programme was to end. This policy had delivered food, oil and military supplies to the Allies free of charge during the war. Britain alone had received over $30 billion worth of aid.

This unexpectedly abrupt termination represented a huge financial headache for the British government.

German Refugee Crisis

On 24 August, British newspapers published the first reports of the unfolding German refugee crisis.

The Potsdam Agreement stipulated that former German territories east of the Oder-Neisse were to be transferred to Poland, with their communities of ‘ethnic Germans’ forcibly transferred westwards. In the shadow of the brutal Nazi occupations of Eastern Europe, violence and reprisals were commonplace.

Altogether, over 14 million refugees were moved and many ended up in the British Zone of occupied Germany. Army authorities struggled to deal with this huge influx of people amid existing shortages of food, shelter, transport and fuel.

British Army of the Rhine

On 25 August, Field Marshal Montgomery’s 21st Army Group was officially redesignated as the British Army of the Rhine (BAOR). This force would help to administer the military government of Germany.

It was the second such force in the Army’s history. The first BAOR had been formed after the First World War and was in operation from 1919 to 1929.

Preliminary Japanese surrender signed at Government House, Rangoon, Burma

On 28 August, senior Japanese officers signed a preliminary surrender agreement to facilitate the Allied reoccupation of Southeast Asia. It was a precursor to the signing of a final surrender on 2 September.

The Allied Occupation of Japan, 1945-52

The Allied occupation of mainland Japan began on 28 August with the arrival of a small detachment of US personnel.

In February 1946, soldiers of the British Commonwealth Occupation Force - composed of Australian, British, Indian and New Zealand personnel - also deployed to Japan. (Pictured above is the formation badge of British Commonwealth Forces during this period.)

The occupation was devised as a means of stopping Japan from becoming a threat to world peace once again. It included large-scale purges of conservatives and nationalists, as well as demilitarisation and constitutional reform.

Yet from the outset, it was less ambitious than its equivalent in Germany. Emperor Hirohito remained as head of state and, from 1947, many of those previously purged were permitted to re-enter national politics.

Prisoners of War

Thousands of British POWs remained in Japanese captivity. The first weeks after VJ Day were an uncertain time for these men, who awaited their liberation with incomplete news of global events and often limited supplies of food.

‘Manner [sic] from Heaven! The long expected planes came over today. They treated us to a brilliant exhibition before finally indicating that they had something to drop. A single engine transport flew low over camp and opened his bomb traps, and there they were 6 kitbags full, we cleared the square and the transport made another run dropping his loads plum in the middle of the square, how the lads cheered! It turned out to be a private present made up by the crew of the aircraft carrier Hancock. What a thrill it was to read an American newspaper and learn about the surrender of Germany or to eat a despised K ration and smoke a stateside cigarette. It hardly seems possible that only a fortnight ago this camp’s morale was at its lowest.’Diary of Corporal Abraham Gumburd, Middlesex Regiment, prisoner of war awaiting his liberation, Japan — 28 August 1945

British and Allied Forces in Southeast Asia

In the aftermath of VJ Day, British and Allied forces retook numerous territories lost to Japan during the war.

In many cases, pre-existing invasion plans were adapted and brought forward to enable the rapid restoration of Britain’s imperial rule. But the huge distances and logistical challenges involved in these operations still resulted in sizeable delays.

Restoration of British rule in Hong Kong

British personnel arrived in Hong Kong on 30 August and reoccupied the colony following the Japanese surrender.

The caption on this salvaged Vickers machine gun (pictured) reads: ‘Buried by 1st Bn The Middlesex Regt (DCO) in Hong Kong / to prevent its capture by the Japanese 1941. Recovered after victory in the Far East’

Operation Tiderace

On 31 August, troops set sail from Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) and Burma (now Myanmar) to retake Singapore. A few days later, the 5th Indian Infantry Division was the first unit to arrive.

On This Day: 1945

This is the eighth instalment of a series exploring the British Army's role in 1945 – one of the most decisive years in modern history – drawing upon the National Army Museum's vast collection of objects, photographs and personal testimonies.

Throughout 2025, a new instalment will be released each month that focuses on events from 80 years beforehand. The series will highlight the everyday experiences of Britain’s soldiers alongside events of grand historical significance.