The British in Belgium

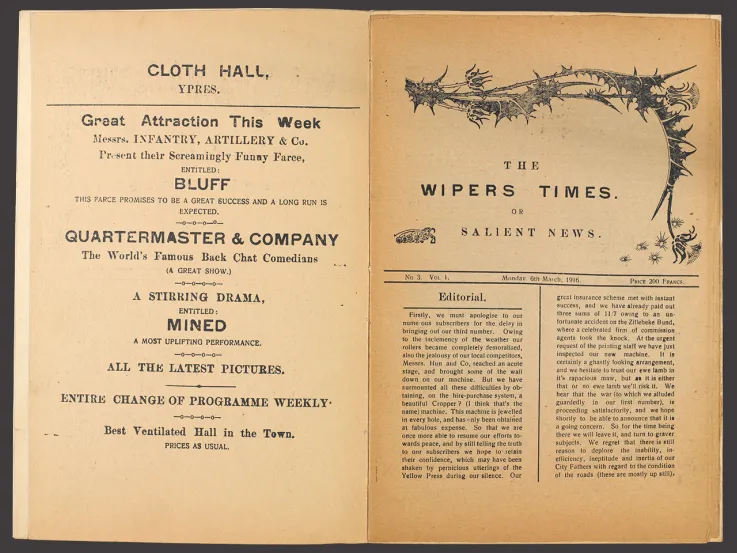

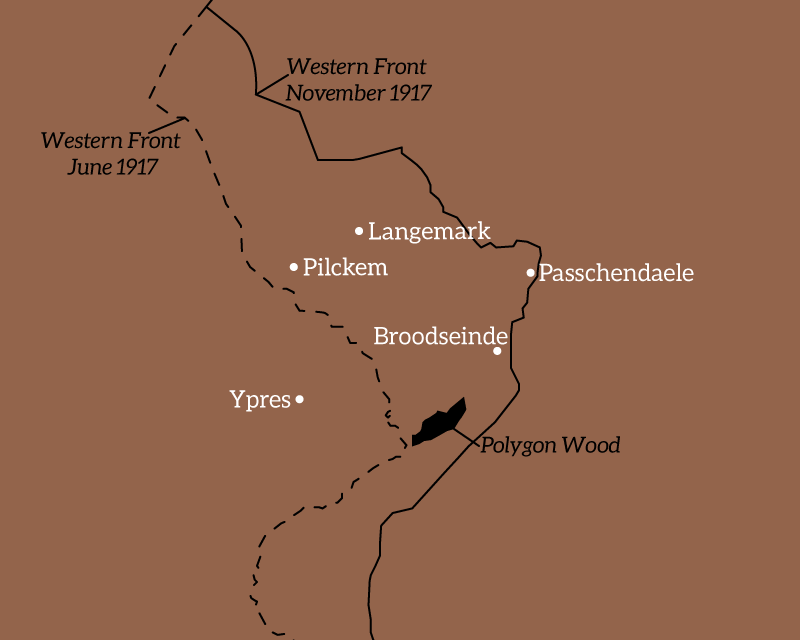

In 1917, British positions in Belgium were based around the city of Ypres, where they had been since the beginning of the First World War (1914-18). They occupied a bulge in the lines of trenches, known as a salient.

Map of the area around Ypres, Belgium, 1917

Strategically important, it was fought over ferociously during the First Battle of Ypres in 1914, and again the following year during the Second Battle of Ypres. Passchendaele would be the third - and largest - major battle in the area in three years.

Ypres was probably the most dangerous area for British soldiers on the whole Western Front. Surrounded by the Germans on three sides and overlooked by high ground, it was very vulnerable to German fire.

The plan for Passchendaele

The British had wanted to attack in the Flanders area in 1916, but had conceded to French desires to launch a joint assault on the Somme. In 1917, after the Arras offensive which had brought such early success for the British, General Sir Douglas Haig planned to launch a major attack in the Ypres Salient, and force the breakthrough he believed would win the war.

Haig aimed to capture the high ground surrounding Ypres, including the Passchendaele ridge, through a series of smaller battles. It would be a major decisive action to break through the German defences. This attack, working with the French, would culminate in the conquest of the Belgian coast and would help to alleviate the growing threat of the German submarines operating from Belgian ports.

It was an ambitious and risky plan. But it did not learn the lessons from the Somme the previous year, or take into account the Army's strained resources after the Arras offensive earlier in 1917.

‘In my opinion the war can only be won here in Flanders.’General Sir Douglas Haig — 13 August 1917

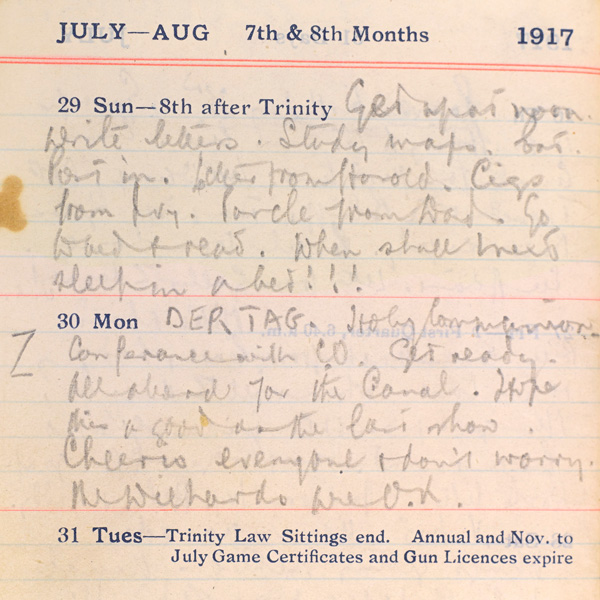

The battle begins

After a preliminary artillery bombardment of two weeks - which saw 3,000 guns fire millions of shells at German positions - the great offensive began at 3.50am on 31 July 1917.

On the first day, at Pilckem Ridge, the British, and particularly their French allies, were able to make some gains, but not without cost.

During the afternoon of 31 July, it began to rain heavily. British artillery observers lost sight of the advancing troops and were unable to support them as the Germans counter-attacked. This resulted in the loss of captured ground.

The rain continued and quickly turned a landscape already smashed by three years of fighting into a swampy quagmire. It affected the British and French, as they tried to advance across heavily contested ground, more than the German defenders. In particular, the rain made supplying the guns, and moving them forward, virtually impossible.

After the opening day, both sides made efforts to strengthen their positions. But by 2 August, the rain had made any kind of strategic movement all but impossible. As a result, the whole Passchendaele offensive was postponed for several days.

Treacherous fighting conditions

This painting by Lieutenant Richard Talbot Kelly shows the difficulties artillery crews had in getting ammunition to their guns due to the rain.

Talbot Kelly himself was wounded on 5 August 1917. A shell exploded nearby and, while he suffered internal injuries, he survived.

He wrote afterwards in his memoirs: 'One does not hear the shell that gets one. If the ground had not been a bog and as soft as it was it is absolutely certain that I would have been blown to bits.'

The offensive continues

Renewed effort was made in new battles. At Langemarck (16-18 August 1917), the French once again made substantial gains and the British were also able to take some ground, but German counter-attacks forced them back.

Rain once again hindered any attempts at attack. And morale among the German defenders remained higher than the British generals expected.

New tactics

The Battle of the Menin Road (20-25 September 1917) witnessed the first use of General Herbert Plumer’s ‘bite and hold’ strategy as the British tried to regain the initiative.

With the British Army's earlier attempts to break through on a wide front having been halted by the deep German defence system, Plumer instead selected for attack a small part of the German front line. This would be heavily shelled and then assaulted in strength.

The advancing troops would stop once they had penetrated 1,500 yards into the German lines. At this point they would dig in, and another wave of attacking troops would pass through them to attack the next objective. The original attackers would then consolidate the ground they had taken, and become the new reserve for future advances.

Using this tactic became possible when more artillery was deployed, thanks partly to the ground drying out between late August and September. It meant that British soldiers did not move beyond where they could be supported. In addition, they were aided by more and better aircraft carrying out air defence, artillery observation and ground-attack sorties.

This meant that when the German counter-attack was launched, instead of finding a mass of exhausted and disorganised men at the limit of the Allied advance, they would find a well organised defensive line still in range of supporting artillery.

Further success

The Menin Road operation was a success. Most of Plumer’s objectives were captured on the first day. German counter-attacks were repulsed on the first and second days of the operation. Three quiet days then followed. The battle ended with a final German counter-attack on 25 September, again repulsed without serious problems.

The Allied forces made two further successful attacks in September and October at Polygon Wood and Broodseinde and drove the Germans back to the top of Passchendaele ridge.

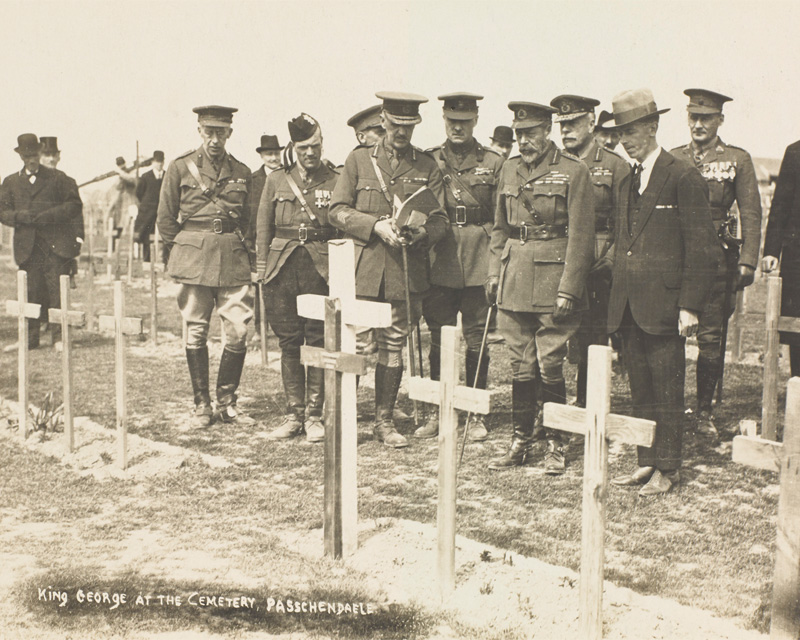

For king and another country

The army at Passchendaele was the largest Britain had ever fielded, but it wasn’t only made up of British soldiers. Men from Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), India, Newfoundland and the Caribbean all served alongside British units, and shared in the hardships of the battle.

Australian soldiers were used from September to try and regain the momentum, making the most of better weather to help carry the advance. But the weather turned again, and they too struggled. There would be 38,000 casualties among Australian units fighting in the Passchendaele offensive.

An Australian soldier’s story

Jack Bassett had been born in Britain and emigrated to Australia before the First World War.

At the outbreak of the war, he attempted to join the army to return to Europe and fight. It took five attempts before he was accepted.

He fought on the Western Front from 1916, and at Polygon Wood in October 1917. He survived the battle, but his health collapsed and he was invalided from service in October 1918.

He died in hospital of a weak heart on 10 January 1919.

The Canadians are coming

In mid-October, with the battle bogging down due to British and Australian exhaustion, the stubborn German defence and the bad weather, Haig sent for the Canadians to make a final push and try to salvage a victory.

Despite the objections of General Sir Arthur Currie, commander of the Canadian Corps, the Canadians were committed to battle on 26 October. Passchendaele ridge was finally captured on 10 November.

Currie estimated that throwing the Canadians into battle at Passchendaele would result in 16,000 casualties. He was eerily accurate: 15,654 Canadians were killed or wounded.

Judging Passchendaele

The British suffered 300,000 casualties fighting for Passchendaele, and inflicted around 260,000 on the Germans.

The British had taken the high ground around Ypres and advanced five miles. But was the return worth it? Could, or should, the battle have been called off earlier rather than fighting on in such atrocious conditions?

The battle has been argued about ever since 1917. How much was achieved and at what cost? Was it a victory or a defeat?

‘Passchendaele was indeed one of the greatest disasters of the war... No soldier of any intelligence now defends this senseless campaign.’Prime Minister Lloyd George reflecting on the battle — 1938

The legacy

Haig was unrepentant after Passchendaele and considered it a success. He wrote in his report after the battle, ‘The ultimate destruction of the enemy’s field forces has been brought appreciably nearer.’ But simply eroding German strength wasn’t what he had set out to do at the beginning of the battle: he had wanted a breakthrough.

In 1918, to better organise their defence in the face of the German Spring Offensive, the British abandoned their positions on the Passchendaele ridge without firing a shot. What had taken months and cost thousands of lives was surrendered meekly. Today, Passchendaele remains a vivid symbol of the hardship of fighting on the Western Front.