Detecting the enemy

Only one cavalry division arrived in France with the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) in August 1914. But it made a crucial contribution early on, helping to detect the advancing German First Army. This gave the BEF time to take up a defensive position along the Mons-Condee canal and temporarily halt the Germans on 23 August.

During the first few months of the war, the cavalry continued to be utilised in traditional roles - carrying out reconnaissance, guarding the BEF’s flanks, defending the rear, and charging approaching enemy formations. But things were beginning to change.

Charge

On 24 August 1914, the 9th Lancers and the 4th Dragoon Guards attempted a charge across an open field at Audregnies. Facing an unbroken German line of rifle, machine-gun and artillery fire, their ranks were decimated.

Firepower had proven its effectiveness over élan and courage. The days of the mass cavalry charge were over.

Firepower

However, cavalrymen could also fight on foot. And they were trained to shoot with deadly effect like their infantry comrades. While they may have been armed with a sword or lance in 1914, cavalry troopers carried the Short Magazine Lee Enfield Rifle, too.

Cavalry units were also armed with Hotchkiss and Maxim machine guns, which provided additional mobile firepower. When they were accompanied by the guns of the Royal Horse Artillery, cavalry formations became even more formidable.

Mobile war

As a result, they were able to fight in a mounted and dismounted role to great effect in a series of highly mobile holding actions at Le Cateau (26 August), Étreux (27 August), Cerizy (28 August), Néry (1 September), Crepy (1 September) and Villers-Cotterêts (1 September).

They then fought in the Allied counter-attacks on the Marne (5-12 September) and the Aisne (13-28 September), and during a period of mobile fighting from late September to the end of November 1914, known as the ‘Race to the Sea’.

Mobile reserve

Although static trench warfare set in following the First Battle of Ypres (20 October to 22 November 1914), cavalry units could still act as a fast and highly mobile reserve. During the Second Battle of Ypres (22 April-25 May 1915), dismounted cavalry units helped plug the gap in the line following the German attack.

Exploiting the breach

Undoubtedly, cavalry lent itself more to mobile conflict rather than the stalemate of trench warfare. But the British High Command still believed that cavalry was needed to exploit any planned breakthrough. This ‘Big Push’ would bring the return of mobile warfare and the liberation of France and Belgium.

Mounted units would exploit this breach using their superior speed to reach the enemy's rear positions, and destroy supply and communications lines. Until that moment came, they could fight in a dismounted role.

Expansion

By 1915, the British cavalry force on the Western Front had grown to include three British divisions (1st, 2nd and 3rd), two Indian divisions (1st and 2nd), which arrived in November-December 1914, and the Canadian Cavalry Brigade, which arrived in April 1915.

Waiting

For the next three years, the typical cavalry experience consisted of periods of waiting and frustration.

For example, on the morning of 15 July 1916, the 18th King George's Own Lancers were in position to follow up an infantry attack near Mametz on the Somme. However, the infantry's inability to make headway against the Germans resulted in the cavalry returning to the rear at the middle of the day.

Attacks were planned, and cavalry were assembled in the area behind these attacks in the hope of following up a successful infantry advance. But the static and attritional nature of much of the fighting meant that this did not come to pass. Instead, many cavalry soldiers continued serving as infantry.

Work behind the lines

The cavalry also had several important roles to play in the rear areas. These included traffic control, prisoner escort duties, mounted police work and helping to construct fortifications and trenches.

Smaller gains

If the cavalry could not exploit a large-scale breakthrough, sometimes they could use their speed, mobility and dismounted firepower to support the infantry in establishing and then broadening smaller gaps secured in the enemy lines, like at Monchy-le-Preux near Arras (1917).

Through these ‘bite and hold’ methods, some senior officers hoped that the cavalry might even help create the conditions for a major breakthrough.

At Cambrai (1917), where four cavalry divisions saw action, the opportunities for a large breakthrough of tanks supported by cavalry proved illusory. Enemy resistance, communication difficulties and delays in sending forward reinforcements halted the advance. But the cavalry still played a vital role in reinforcing recently-won positions and then helping resist German counter-attacks.

Mobility returns

Following the German Spring Offensive (March 1918), and the Allied counter-attack at Amiens (8-12 August), mobility returned to the Western Front.

During the German advance, the cavalry helped stem their attacks, often acting as a mobile strike force sent to restore critical situations, and also fighting numerous rearguard actions.

At Moreuil Wood, on 30 March 1918, parts of the Canadian Cavalry Brigade fought on foot with fixed bayonets, while a mounted squadron of Lord Strathcona’s Horse charged German infantry, crucially delaying their advance.

Lord Strathcona’s Horse on the march, 1918

‘I have been fighting hard for the last 48 hours to save Amiens but the only troops I have are the remnants of the Fifth Army who are desperately tired and greatly demoralised but by dint of helping them with some cavalry at points where they have been hard pressed we have so far been able to maintain our line’.Letter from General Sir Henry Rawlinson to Lord Derby — 30 March 1918

Advance

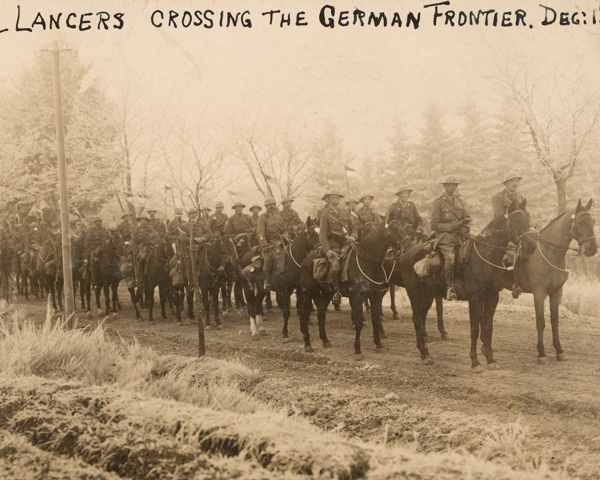

Eventually, the German offensive was defeated and the Allied victory at Amiens began the period known as the ‘Hundred Days’. This was a series of offensives along the line, which drove the Germans back until the Armistice in November.

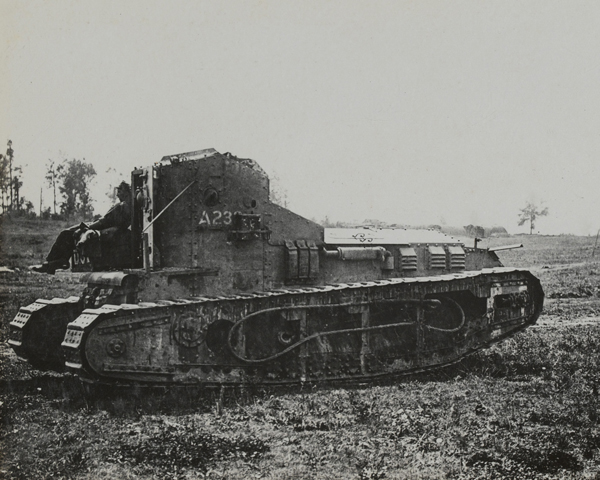

The cavalry now returned to a mounted and manoeuvrable role, working alongside armoured cars and new Whippet light tanks as screens for the advancing armies. Mounted units carried out reconnaissance to locate the retreating enemy, harried his forces and prevented the formation of a stable defensive line.

‘The country was ideal for cavalry action and they took full advantage of the favourable conditions. In places they penetrated considerably beyond the Amiens outer defences, inflicting heavy casualties on the enemy and capturing large numbers of prisoners and guns'.General Sir Henry Rawlinson's report on cavalry operations — 28 August 1918

All arms

Cavalry was now viewed increasingly as one of several mobile elements that also included aircraft, motor vehicles and bicycle mounted troops. Mounted units became part of a sophisticated and co-ordinated ‘all arms’ attack.

During this period, the cavalry had some striking local successes. The 5th Dragoon Guards, for example, captured or killed over 700 Germans during an attack on soldiers disembarking from a troop train at Harbonniers on 8 August 1918.

At Le Cateau on 9 October 1918, the Canadian Cavalry Brigade advanced eight miles (13km) across a three-mile front, capturing over 400 prisoners and 100 machine guns, along with several pieces of enemy artillery.

Aftermath

The importance of tanks, armoured cars and motor vehicles in the Allied victory of 1918 signalled that traditional cavalry roles were no longer needed.

After the war, the High Command hoped to establish a small but highly mechanised army. But, in an era of economic retrenchment, the replacement of horses with tanks and other vehicles was somewhat piecemeal.

Nevertheless, the Army reduced the number of cavalry regiments from 31 to 22. And in the late 1920s, these began mechanising, a process that was largely complete by the outbreak of the Second World War (1939-45).