Uprising

The Easter Rising took place against a backdrop of increased political tension. This was caused by British reluctance to implement Home Rule - enacted by the 1914 Government of Ireland Act - and their assertion that it could only be done if military conscription was also introduced to Ireland.

This linking of conscription and Home Rule outraged Irish nationalists of all persuasions. But the militant Irish Republican Brotherhood, along with sections of the Irish Volunteers and Irish Citizen Army, opted for a violent response.

British response

The revolt came as something of a shock to the British. Their intelligence mistakenly believed the plot had been postponed following the Royal Navy’s recent interception of smuggled German weapons.

It took the better part of a day to organise a response, which was inevitably armed. There were only a few troops in Dublin, so soldiers were rushed there from elsewhere in Ireland, including the Curragh in County Kildare, and from across the sea in Britain.

Street fighting

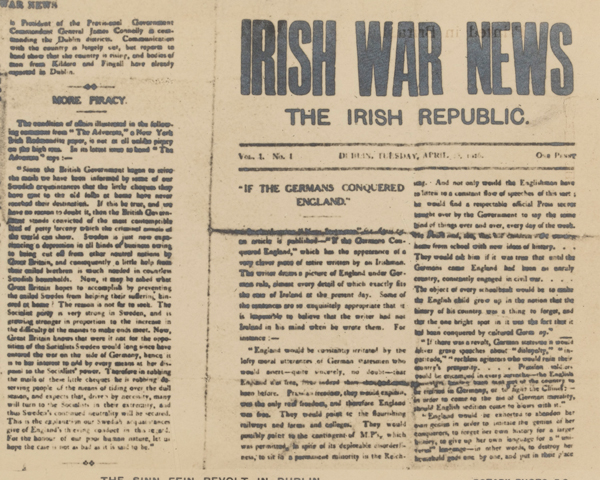

Martial law was declared across Ireland, but the fighting was largely confined to Dublin. It focused around the General Post Office (GPO) building, where the rebels proclaimed the establishment of the Irish Republic.

‘Balls Bridge was reached at noon and as the advanced guard crossed a heavy fire was opened on them from the front and the flank. It was a trying ordeal for such young troops of whom many had only three months’ service, especially as it was impossible to see where the enemy, who were concealed in the houses, were firing from… The 2/7th Battalion bombed in the doors or houses occupied by the enemy and drove them out, but the battalion continued to lose men heavily, all along Northumberland Road. The corner house in Haddington Road was strongly held, and only taken after a most gallant attack in which several lives were lost. Lieutenant Foster succeeded in entering on the other side by breaking a window and with the aid of bombs attacked the defenders, Lieutenant Foster bayoneting three men on the stairs. The house then caught fire and lit up the whole neighbourhood. There were nearly 80 casualties amongst the other ranks. A house was occupied as a dressing station and throughout the afternoon a Red Cross ambulance with a lady, Mrs Chaytor, all honour to her, sitting beside the driver, drove continually under heavy fire to the dressing station and removed wounded men to hospitals. Women also rushed out of houses and dragged the wounded into safety.’Unpublished memoirs of Brigadier General Ernest Maconchy — 1920

Collapse of the rebellion

The rebels were slowly driven back in violent street fighting. Many of Dublin’s landmarks became the focus of bitter struggles, including the South Dublin Union Workhouse (now St James’s Hospital), which was flying the flag of the Irish Volunteers. After several days of intense fighting there, a breach in the wall was made and the building finally occupied.

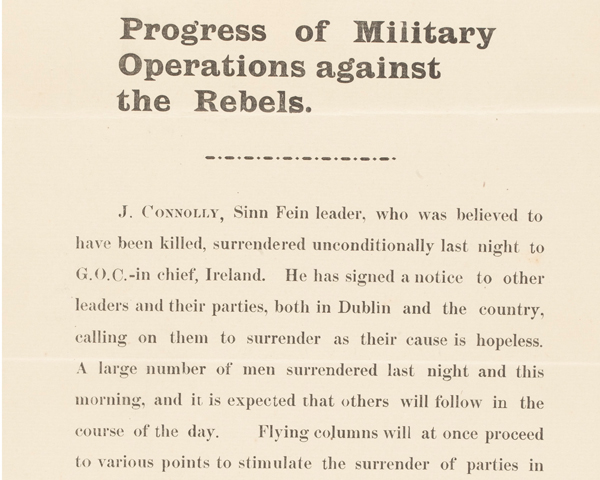

The city was divided into quarters and the rebels steadily pushed into one area, all exits from which were closed. Eventually, only the GPO remained in their hands. The arrival of British infantry reinforcements and light artillery ended the siege there on 29 April.

British losses were 120 killed and nearly 400 wounded. Around 60 men from the Irish Volunteers and Irish Citizen Army were killed during the revolt. Over 180 civilians also died.

Public opinion

The rising lacked wide-scale public support at its outset, and not only among Unionists opposed to Irish independence. Many Dubliners had relatives fighting in the British Army and felt it was a betrayal of them; others objected to the violence used by some rebels and to the disruption to food supplies.

Some people saw the violence as an opportunity to loot shops. Others watched the fighting with a mixture of indifference and curiosity.

‘Mothers held their children up at the windows of houses to see the soldiers… and maids came out of the houses to watch the fight, regardless of the bullets which were flying about very freely, only to scream and throw their aprons over their heads and run in when a bullet came unpleasantly close.’Unpublished memoirs of Brigadier General Ernest Maconchy — 1920

Executions and internment

The subsequent British military occupation of the city and the internment of over 1,400 Republicans - many of whom had little do with the rising - angered many and increased electoral support for Sinn Féin.

Most importantly, the British reprisals against the revolt’s leaders, 16 of whom were executed, generated great sympathy for Republican ideas.

Lessons

Many Irish Republicans took a dim view of the rising’s military strategy. Michael Collins, who had fought at the GPO, believed the policy of capturing and then holding indefensible and vulnerable posts in the middle of the capital to be foolhardy. Such places were impossible to escape from and hard to supply.

It was a lesson he would not forget when leading a successful guerrilla war against the British during the subsequent Irish War of Independence (1919-21).