Thomas Edward Lawrence, 1919 (Public domain via Wikimedia Commons)

Antiquities

Thomas Edward Lawrence was born in Tremadog, Wales on 16 August 1888. From a young age he exhibited an active interest in architecture, monuments and antiquities. At the age of 15, he and a friend completed a survey of parish churches in Oxfordshire, Berkshire and Buckinghamshire, and monitored building sites in Oxford to ensure that any antiquities found were properly catalogued and presented to the Ashmolean Museum.

Between 1907 and 1910, Lawrence studied History at Jesus College, Oxford. During this time, he toured France by bicycle, collecting photographs, drawings and measurements of medieval castles. This would form the basis of his dissertation. In 1909, he completed a remarkable solo 1,000-mile trek through Ottoman Syria visiting Crusader castles.

Following his studies, Lawrence became an archaeologist. He worked in Egypt, Palestine and Syria, at that time all part of the Ottoman Empire. This first-hand knowledge and experience earned him a posting to Cairo after he enlisted in the British Army in October 1914. He served in the intelligence staff of the British Middle East Command in the First World War campaign against the Turks.

Liaison officer

In 1916, Lawrence was posted to Hejaz, in modern Saudi Arabia, to work with the Hashemite forces. The campaign would secure him lasting fame in British popular legend.

His role was to act as a liaison officer between the British government and the Arab tribes. The British were attempting to rally the Arabs against the ruling Ottoman Empire. They hoped that an internal revolt could help break the deadlock in the war in the Middle East.

Lawrence was not the only British officer engaged in this work, but he is undoubtedly the most famous. His role required diplomatic as well as military skills, and he was able to build an effective relationship with Emir Feisal - a son of Sherif Hussein of Mecca and an important commander in his own right.

Lawrence in the desert in traditional Arab garb, c1917

Lawrence was able to exert enough influence to convince the Arab leaders, Feisal and Abdullah I, to support Britain. During the resulting Arab Revolt, guerrilla attacks against the Ottoman Empire were co-ordinated with wider British strategy.

Lawrence developed a particularly close relationship with Feisal. His Arab Northern Army became the main beneficiary of British aid. At the heart of this relationship was Lawrence’s willingness to adapt to the cultural norms of his allies. This included speaking their language, staying with them, and adopting their dress.

‘Feisal asked me if I would wear Arab clothes like his own while in the camp. I should find it better for my own part, since it was a comfortable dress in which to live Arab-fashion as we must do. Besides, the tribesmen would then understand how to take me... If I wore Meccan clothes, they would behave to me as though I were really one of the leaders.’TE Lawrence, 'Seven Pillars of Wisdom' — 1922

Mobilising the Arabs

Lawrence was well suited to his liaison role. His pre-war experience meant that he understood the region and the language. He was able to motivate the Arab tribesmen and identified Feisal as the most successful leader in the Arab Revolt against the Ottoman Empire.

He stayed with Feisal for two years and helped him to lead the Arabs north from Hejaz to Syria. Lawrence believed that this would be the foundation of an independent Arab state after the First World War.

Lawrence’s approach delivered great success. Aqaba fell to the Arabs on 6 July 1917. And at Tafileh in January 1918, Lawrence and the Arabs turned a defensive battle into a rout of the Turkish forces.

Lawrence also organised the Hejaz Arabs to conduct guerrilla attacks. They targeted Turkish lines of communication, including telephone wires and the railway that led to Palestine - a crucial supply route. The Turks were forced to dedicate thousands of troops to protecting rear areas and prevented from concentrating against the main British advance in Palestine.

Lawrence and the Arab troops marched alongside General Sir Edmund Allenby’s forces when they entered Damascus on 1 October 1918.

‘I gave him a free hand. His co-operation was marked by the utmost loyalty, and I never had anything but praise for his work, which, indeed, was invaluable throughout the campaign. He was the mainspring of the Arab movement and knew their language, their manners and their mentality.’General Sir Edmund Allenby, commander-in-chief of the Allied Egyptian Expeditionary Force on TE Lawrence

Sharing lessons

Lawrence’s relationship with the Arabs impressed his fellow officers. He was keen to share lessons and observations with them on how to best work with the Arab tribesmen.

In June 1916, he founded a journal called the The Arab Bulletin so that experts could discuss the Arab Revolt and share information and ideas. On 20 August 1917, he published a briefing note in it called ‘Twenty-Seven Articles’ that was designed as an aid to 'beginners in the Arab armies'.

Lawrence’s actions also attracted praise from his superiors. But it was domestically amongst civilians that he would achieve enduring fame.

‘Do not try to do too much with your own hands. Better the Arabs do it tolerably than that you do it perfectly. It is their war, and you are to help them, not to win it for them. Actually, also, under the very odd conditions of Arabia, your practical work will not be as good as, perhaps, you think it is.’'Twenty-Seven Articles' by TE Lawrence in 'The Arab Bulletin' — 20 August 1917

Sykes-Picot

Despite his efforts, Lawrence was unsuccessful in his mission to promote Arab self-determination. He represented the Arabs with Feisal at the Paris peace conferences in 1919, and lobbied again on their behalf at the Cairo conference in March 1921.

Unfortunately, the British and French governments had already secretly resolved how they would carve up the Middle East between themselves in 1916 under the Sykes-Picot agreement.

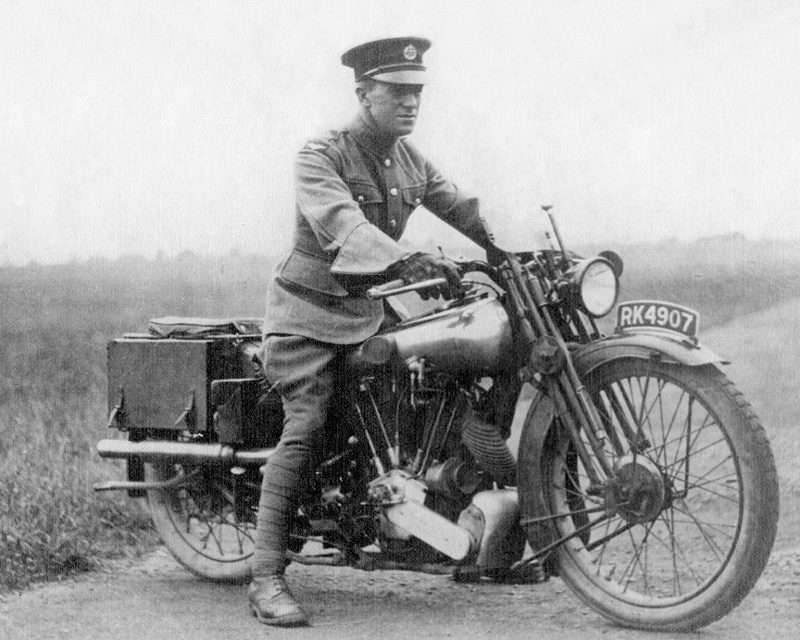

Lawrence on his motorcycle, c1925 (Public domain via Wikimedia Commons)

Withdrawal from public life

In 1921, Winston Churchill chose Lawrence as his adviser. Keen to withdraw from public life, Lawrence resigned the following year. He then joined the Royal Air Force (RAF) under an assumed name, but he was found out and had to leave. He later joined the Tank Corps , also under an alias, before returning to the RAF in 1925.

Lawrence published his major work, Seven Pillars of Wisdom, in 1926. This gave an embellished autobiographical account of the Arab Revolt. He died following a motorcycle crash in 1935.

Peter O'Toole as Lawrence in 'Lawrence of Arabia', (1962) (© Columbia Pictures)

Lawrence in popular culture

As impressive as his military feats were, it was the image that Lawrence created for himself - of the European adopting Arab dress and customs - that furthered his reputation and sealed his legend in popular culture.

In August 1919, the American journalist Lowell Thomas launched a multimedia show in London called ‘With Allenby in Palestine’, which included a lecture, dancing and Arabic music. Lawrence had initially featured in a supporting role, but it soon became clear to Thomas that images shot of Lawrence on campaign had captured the public imagination.

Thomas arranged to photograph Lawrence again, this time wearing white robes and carrying the jambiya that Sherif Nasir had given him. With these new photos, he relaunched his show as ‘With Allenby in Palestine and Lawrence in Arabia’ in early 1920. It was extremely popular - seen by more than 3 million people between 1920 and 1924 - and made Lawrence a star.

In 1962, the legend of Lawrence was renewed with David Lean’s epic feature film 'Lawrence of Arabia'. Its star, Peter O’Toole, was nominated for an Academy Award for his performance. Once again, it was Lawrence’s appearance in Arab dress that was central to the film’s marketing.

Lawrence's robes and dagger were prominent in the film. When Sherif Ali, played by Omar Sharif, burns Lawrence’s British kit before giving him his Arab robes, it is a moment of enormous dramatic and narrative significance. It marks Lawrence’s cultural transition from British officer to a member of the tribe and helps complete his cultural assimilation, making his mission more successful.

The attack on Aqaba, for which Lawrence was awarded the jambiya, was no doubt overly dramatised in the film. But the dagger and the robes are the iconic items at the heart of the movie. They have created the prism through which the modern world remembers Lawrence, and reflects on Britain's role in shaping the Middle East.

See it on display

Come and see Lawrence's silk robes and jambiya dagger on display in our Global Role gallery.