Early life

The eldest son of the 3rd Duke of Rutland and his wife, Bridget Manners (née Sutton), John Manners (1721-70) was educated at Eton and Trinity College, Cambridge. On returning home from a 'Grand Tour' of the Mediterranean in 1742, he started his political career as the Member of Parliament (MP) for Grantham.

He never inherited the dukedom as he failed to outlive his father, and was known instead by his father's subsidiary title, Marquess of Granby.

Jacobites

Granby was commissioned as colonel of the 'Leicester Blues', one of the 'noble' short-service regiments raised to fight 'Bonnie Prince Charlie', the Young Pretender, in 1745. Although his unit spent most of its time garrisoning Newcastle, Granby volunteered for service on the Duke of Cumberland’s staff, going on to fight at Culloden (1746).

He then served in Flanders as an intelligence officer during the latter stages of the War of the Austrian Succession (1740-48).

Granby was returned as MP for Cambridge in 1754, and continued his political career alongside his military duties. He was promoted to major-general in 1755 and appointed colonel of the prestigious Royal Horse Guards (The Blues) by King George II in 1758.

Germany

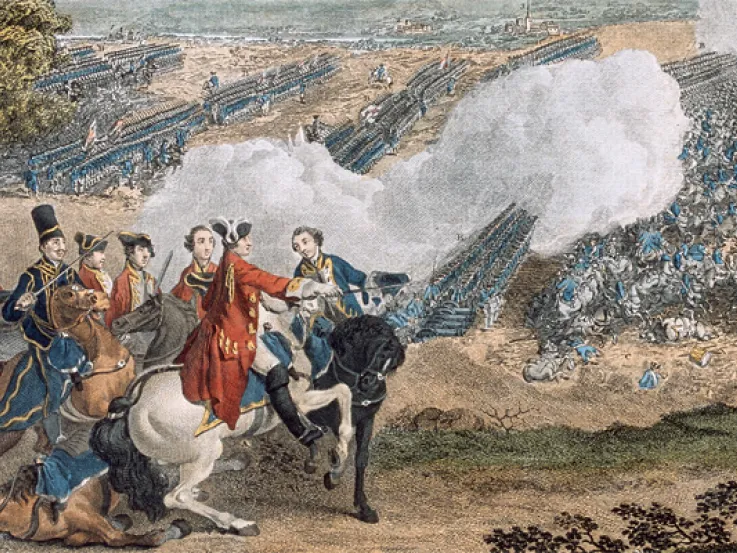

During the Seven Years War (1756-63), Granby initially commanded a cavalry brigade in Germany. While there, he helped reorganise the mounted units into light and heavy roles and improved their training.

He commanded the second line of cavalry at Minden in 1759, and was then given command of the entire British force in Germany after Lord George Sackville’s dismissal. That year, he also became Lieutenant-General of the Ordnance.

Always a fearless battlefield commander, he famously led a cavalry charge against the French at the Battle of Warburg on 31 July 1760 that caused his hat and wig to blow off, giving rise to the expression 'to go at (something) bald-headed'.

His victory at Warburg, where he skilfully deployed his cavalry and horse artillery to maximum effect against a much larger enemy force, marks him out as one of the great commanders. He went on to help defeat the French again at the battles of Vellingshausen (1761) and Whilhelmsthal (1762), co-operating well with his German allies.

It was a testament to Granby's reputation as a commander that his French opponent at Warburg and Vellinghausen, the Duc de Broglie, later commissioned Sir Joshua Reynolds for a full-length portrait of him.

Popularity

Granby returned home from Germany to a hero's welcome. Like his contemporary, General James Wolfe, his popularity and celebrity led to him being commemorated in paintings, prints, medals and ceramics.

This popularity was founded not only upon his great personal bravery, but also on his well-known generosity and concern for the welfare of his men. For example, when the 'Leicester Blues' mutinied over withheld wages, Granby paid the money out of his own pocket before they were due to be disbanded.

In April 1762, while colonel of the 21st Light Dragoons (Royal Foresters), he happily paid over £105 (around £22,000 today) for dinner for the whole regiment in the Half Moon Inn at Hertford.

During the campaign in Germany, he made sure he was kept informed about the hospital accommodation his wounded men were given. Edward Penny’s ‘The Marquess of Granby relieving a sick soldier’, showing him acting as a man of charity rather than as a great general, helped secure his public appeal.

A hard drinker himself, Granby also assisted some of his soldiers in setting up as publicans upon their discharge from the Army. To this day, a large number of public houses are named after him.

Final years

Granby later resumed his political career, attempting to steer something of an independent course away from party factions. However, he was less successful in the political world than the military.

He became Master General of the Ordnance in 1763 and was appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Army in 1766. But he eventually resigned both posts following changes in government and continued public accusations of corruption from the pseudonymous political writer ‘Junius’. These charges originated from his changing stance on the government’s attempts to prosecute the Radical MP John Wilkes.

The loss of his official salaries meant that Granby soon found himself pursued by his creditors. He eventually died, deep in debt, at Scarborough in 1770.