State of affairs

By autumn 1945, one of the most significant issues confronting Britain, and the British Army, was the future of empire. For centuries, Britain had soldiers serving in its colonies all over the world. Now, following the defeat of the Axis powers, national independence movements were renewing their calls for an end to colonial rule – and, in some cases, taking direct action against any prospective renewal of European control.

In early October, British and Indian Army commanders accepted the surrender of Japanese troops across Southeast Asia. In Malaya (now Malaysia) and Burma (now Myanmar), thousands of Japanese soldiers were taken prisoner as British colonial rule was quickly reestablished. Yet, in both nations, demands for independence were now more vociferous than ever before.

Many Japanese prisoners of war (POWs) were transported to camps in the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia), where a nationalist revolution was under way. With the Netherlands unable to muster a force capable of retaking control, British and Indian soldiers were deployed to Java with the tasks of reestablishing order, freeing Allied POWs and ultimately reinstating Dutch imperial rule.

At the end of the month, the death of British Indian Army commander Brigadier Mallaby in the city of Surabaya, East Java, intensified the conflict yet further. Fighting quickly spread across Indonesia. In response, Japanese POWs were rearmed to fight as British auxiliaries against an improvised force of republican militias and infantry.

Elsewhere, the work of the British Army remained wide-ranging amid the complex demands of reconstruction. Britain’s soldiers were employed in all manner of roles, from civil engineers to peacekeepers. Alongside the British Army of the Rhine in Germany, there were soldiers based in Austria, Norway, Iran, Iceland and beyond. For some, it provided an opportunity to travel and explore, yet for many the delay in returning home was a source of mounting frustration.

Japanese forces in Malaya surrender

In the weeks after the formal end of hostilities, Japanese garrisons across Southeast Asia continued to surrender following the arrival of British troops.

Pictured above is a katana sword surrendered on 5 October 1945 by the commander of Japanese forces in Kuantan, Malaya, to Lieutenant-Colonel Neil Malcolm Brodie of the 1st Punjab Regiment.

‘I hereby delegate to the Chief Civil Affairs Officer, Malaya, full authority, power and jurisdiction to conduct on my behalf the military administration of the civil population of Malaya.’Directive of Lieutenant-General Miles Dempsey, General Officer Commanding Military Forces, Malaya — 1 October 1945

British forces retake the Nicobar Islands

On 7 October, British forces landed on the Nicobar Islands, a British Indian territory located in the eastern Indian Ocean.

Japanese naval officers are shown above saluting Lieutenant Colonel Nathu Singh and other British Indian officers at a ceremonial landing on the island of Nancowry.

Japanese prisoners sent to Rempang

After British, Indian and Australian forces had reconquered Singapore, they set about renewing control over the island.

Pictured above are some of the thousands of Japanese soldiers and sailors who were taken prisoner and sent to the nearby island of Rempang in the Dutch East Indies.

First British POWs return home from Japanese camps

For British survivors of the Japanese POW camps, the route home was long and arduous. In October 1945, the ocean liner SS 'Corfu' docked at Southampton carrying the first former prisoners to return to Britain.

After years of terrible hardships, many of these men continued to struggle with the physical, psychological and emotional effects of their time in captivity.

Belsen trial

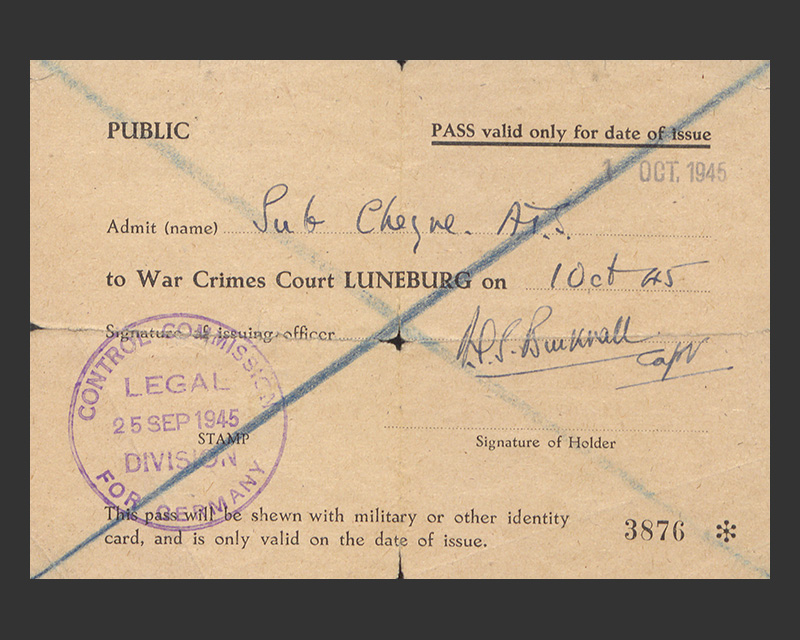

In Lüneburg, Germany, the Belsen trial continued throughout October as a British military court heard evidence of war crimes, including witness testimonies from survivors and liberators of the concentration camp.

These proceedings were held in English, with Polish and German translations. In total, the trial would last for 54 days.

There was a great deal of media interest, and many British personnel sought out opportunities to watch from the public gallery. Shown above is a pass for Subaltern Cheyne of the Auxiliary Territorial Service to attend on 1 October 1945.

Rudolf Hess to face trial

On 8 October 1945, after four years of imprisonment, Rudolf Hess was transferred from Britain to Nuremberg in Germany to face trial.

In May 1941, while Deputy Führer of the Nazi Party, Hess had made a solo flight to Scotland, where he supposedly hoped to arrange peace talks with the Duke of Hamilton. He crash landed near Glasgow, outside the cottage of David McLean (pictured above), and was immediately arrested.

His trip quickly became the subject of numerous conspiracy theories.

‘The Educational Control Officer whom I interviewed at the Göttingen MIL GOV detachment told me that the university was in full swing again, and that whereas 3,000 students were there prewar, the present number was 4,000, and there had been 6,000 applicants for courses! And this just five months after capitulation.’Letter from Lieutenant Colonel Harold Newman to his wife back in Britain on the efforts to restart the German education system — 11 October 1945

British occupation of Austria

In October 1945, the Allied occupation authorities in Austria agreed that the country's first legislative elections could be held the following month. This underlined the much quicker transition from occupation to sovereignty in Austria when compared to the same process in Germany.

Lieutenant Norman Leonard Palmer is pictured above in the Austrian town of Matrei, where he was part of the British occupation army.

A democratic Austria

During the war, the Allies agreed that Austria had been the first victim of Nazism rather than a willing accomplice. Germany’s Anschluss, or annexation, of 1938 was declared null and void.

Given this assessment, the four powers occupying Austria in 1945 (Britain, France, the USA and the Soviet Union) were content to pursue a much less stringent process of denazification and a much more rapid path towards democracy compared to their approach in Germany.

A soldier’s view of Rome

In the months following the end of the war in Europe, the Allied powers gradually relinquished their control over Italian territory. By the end of 1945, the Allied Military Government was all but abolished across Italy as the country prepared to appoint members to a new Constituent Assembly the following summer.

This photograph of Rome was taken by Frederick Cecil Cracknell of the Army Film and Photographic Unit.

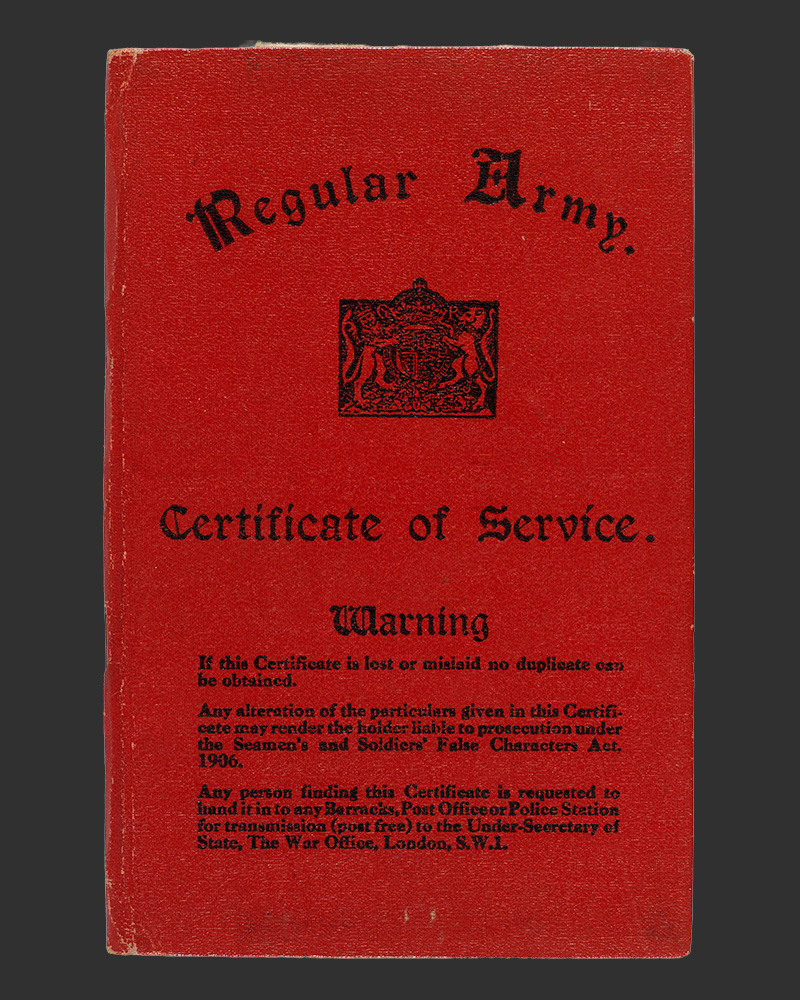

Demobilisation continues

This Regular Army Certificate of Service was a hugely important document for recently demobilised soldiers in postwar Britain.

As proof of service in the Army, it entitled them to various benefits, ranging from government support to employment schemes designed exclusively for ex-servicemen.

‘I have spoken to troops in India, Burma, Hong Kong and Singapore — to say nothing of a large meeting in Egypt and Ceylon... It is impossible for us in Britain to put ourselves in the place of these men who have been often four and five years away from home in the course of the war and who are sometimes married and with young children of whom they have seen little or nothing. They have been living, working and fighting in a climate which for them is extremely testing. They have been soldiers so long that it is not easy to remember they are workmen, craftsmen and professional men who never dreamed of leaving home and work.’Statement in the House of Commons by Jack Lawson, Secretary of State for War — 11 October 1945

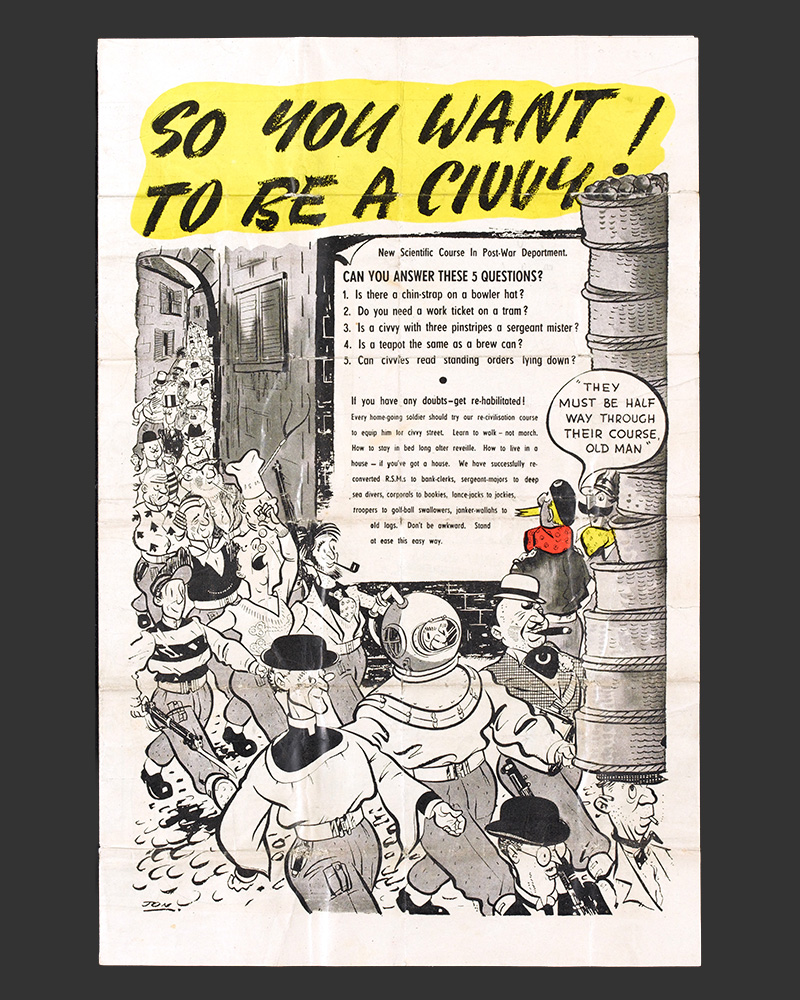

‘So you want to be a civvy!’

This rather amusing illustration encouraged soldiers of the British Army to undertake civilian resettlement training.

It was clear that the transition from war to peace would be challenging for anyone who had grown accustomed to life in the Army. For some, it was all they had known their entire adult lives. These resettlement courses promised to teach attendees how to ‘walk – not march’.

‘We have on board a number of Chinese students. Today the ship played their national anthem and flew their flag at the foremast in honour of the thirty fourth anniversary of the Chinese Republic. They have written an appreciative letter to the captain and subscribed £10 for the Seamen’s Benevolent. A good thing. Also a good thing that they are coming to UK for three years as before the war they almost all went to America for their Western qualifications.’Captain Peter Whitfield Gallup, Royal Field Artillery, on board HMT 'Britannic' during his return to the UK from India — 11 October 1945

The Future of Empire

One of the defining questions of the postwar era was the future of imperialism. For centuries, Britain and the other major imperial powers of Europe had ruled over much of the world. Yet, by 1945, the maintenance of empire was increasingly controversial.

In the face of budding national independence movements, as well as pressure from the ostensibly anti-imperialist United States, there were growing calls for a withdrawal from the colonies.

Partly due to the increased militancy of these independence movements, imperial rule was also becoming unsustainable. With more and more troops required to maintain any semblance of control, the financial and labour costs of empire grew significantly.

In some places – especially in Southeast Asia – the continuation of empire after 1945 required a process of recolonisation following the defeat of Axis forces. This often provoked a fierce backlash from nationalists who had seized the chance to assert their own power, and further increased the potential costs of maintaining imperial rule.

British India

This photograph shows Lady Wavell - wife of Field Marshal Sir Archibald Wavell, Viceroy of India - meeting injured troops during a visit to the Combined Military Hospital, Rawalpindi, October 1945.

Lord and Lady Wavell would continue to fulfil their official and ceremonial duties until India gained independence in 1947.

Fifth Pan-African Congress

15-21 October 1945

Representatives of states across Africa, as well as African diasporas all over the world, met at Chorlton-on-Medlock Town Hall in Manchester to discuss Pan-Africanism. It marked a significant turning point in the history of decolonisation, with attendees unanimous in their calls for independence from colonial rule.

These discussions would have huge implications for the future of the British Empire in Africa and the West Indies, and accordingly the nature of the British Army after 1945.

The Gold Coast Regiment

The Gold Coast Regiment raised a total of nine battalions during the Second World War. These units saw action in Kenya's Northern Frontier District, Italian Somaliland (now part of Somalia), Abyssinia (now Ethiopia) and Burma.

Above, members of the regiment's 7th Battalion can be seen sitting for a photograph near Madras (now Chennai) while awaiting transport back to West Africa in October 1945.

The Future of Burma

Following the reconquest of Burma from Japanese occupation, the British Army oversaw a temporary military administration.

In mid-October, Major-General Sir Hubert Rance was returned to power as the British governor. The British Army remained heavily involved in plans for rebuilding this shattered nation.

However, an increasingly powerful Burmese independence movement challenged any return to imperial control. It would eventually secure the end of British rule in January 1948.

‘Responsibility for the administration of the remainder of Burma was assumed by His Excellency the Governor on 16 October 1945 at 1030 hours when he stepped ashore at the Naval Jetty at Rangoon on his return to Burma.’Report of the Burma Handing Over Commission, overseeing the transfer from a military to a civilian administration when Major-General Sir Hubert Rance was made Governor of Burma — 16 October 1945

Co-ed classes at Camberley

On 20 October, for the first time, women were allowed to take classes alongside their male colleagues at the Army Staff College in Camberley. Attendees included members of the Women's Transport Service of East Africa, the Canadian Women's Auxiliary Air Force and the Auxiliary Territorial Service.

‘We are both very busy organising our next Mess Dance... There is quite a lot to be done. A band to arrange, eats and drinks to be thought of, decorations etc: we have to find out which of the members are asking their own partners for them, and do the providing. The latter is not an easy job... Feeling is running very high at present amongst some of the Service Girls at the recent order which permits men in the Forces to take German girls to army dances in dancehalls or clubs.’Letter from Captain Ronald Hughes, British Army of the Rhine, to his mother — 21 October 1945

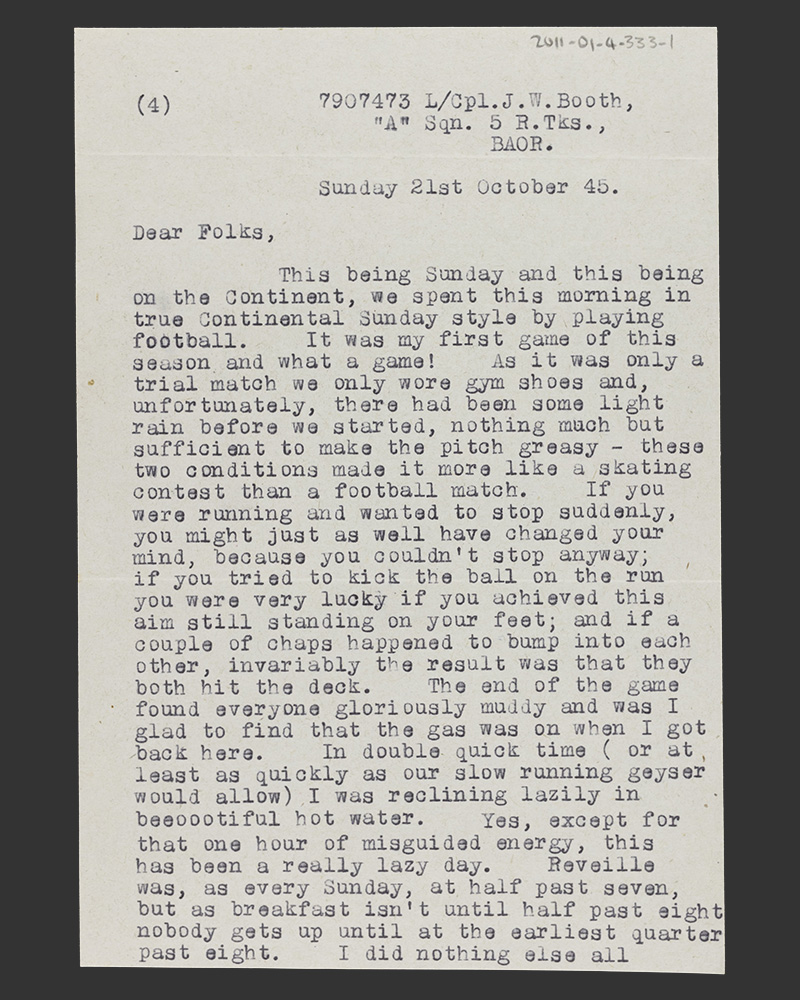

Life in the British Army of the Rhine

In a letter to his parents, dated 21 October 1945, Lance Corporal John William Booth of the 5th Royal Tank Regiment described his life in the British Zone, Germany, as part of the occupying army.

Booth’s letter describes a memorable game of football on an otherwise lazy Sunday.

British soldiers across the world

In late 1945, British soldiers were deployed all over the globe, from Iceland to Iran. For some, it offered an unexpected taste of adventure and opportunities for travel. But many others were impatiently awaiting their demobilisation.

‘The Battalion have now been given a new and somewhat unusual task. Every few days we are requested to send an escort of one officer and approximately 30 tough and well armed N.C.O.s and Guardsmen to conduct either disputed displaced personnel or Wehrmacht Poles or Gestapo and SS men in numbers anything up to 1000 all over Europe.’Diary of Grenadier Guards Composite Battalion covering its activities in Norway, including ferrying refugees and suspected war criminals back to Germany and beyond — 24 October 1945

Image courtesy of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration

At the end of the war in Europe, there were tens of millions of people displaced from their home countries, including prisoners of war, Holocaust survivors and freed slave labourers.

In October 1945, the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) took full responsibility for the administration of Displaced Persons camps in western Europe. British and Allied military authorities continued to assist UNRRA for several years, including with the provision of transportation.

Pictured above is Joseph Schleifstein, a four-year-old survivor of Buchenwald concentration camp, sitting on the running board of an UNRRA truck.

British troops withdraw from Iran

In August 1941, Britain and the Soviet Union undertook a joint invasion of neutral Iran, which culminated in a prolonged military occupation. It was agreed that these Allied troops would leave six months after the end of hostilities.

By October 1945, almost all British soldiers had left the capital, Tehran, in preparation for the final withdrawal the following March. Indian soldiers of the Persia and Iraq Force are pictured returning from Iran after taking part in the occupation.

The reluctance of the Soviets to withdraw their own troops soon led to one of the first major crises of the nascent Cold War.

Formation of the United Nations

24 October 1945

The Soviet Union’s ratification of the United Nations Charter at 4.50pm Eastern Standard Time on 24 October 1945 brought the total number of signatories to 29 and marked the establishment of the United Nations (UN).

After the failure of the League of Nations in the 1930s, there was tremendous interest – and wildly varying opinions – as to exactly how the UN might prove more successful in bringing about world peace.

You can read the full text of the United Nations Charter on the UN website.

‘It is worth noting that this declaration does not start by saying "We, the Governments". It starts by saying "We, the peoples". This, I think, is right, because it expresses the fact that this Charter is an endeavour to put into practical form the deep feelings of all the peoples, including the fighting men who have made it possible to have a Charter at all.’Prime Minister Clement Attlee presenting the Charter of the United Nations to the House of Commons

Indonesian National Revolution

1945-49

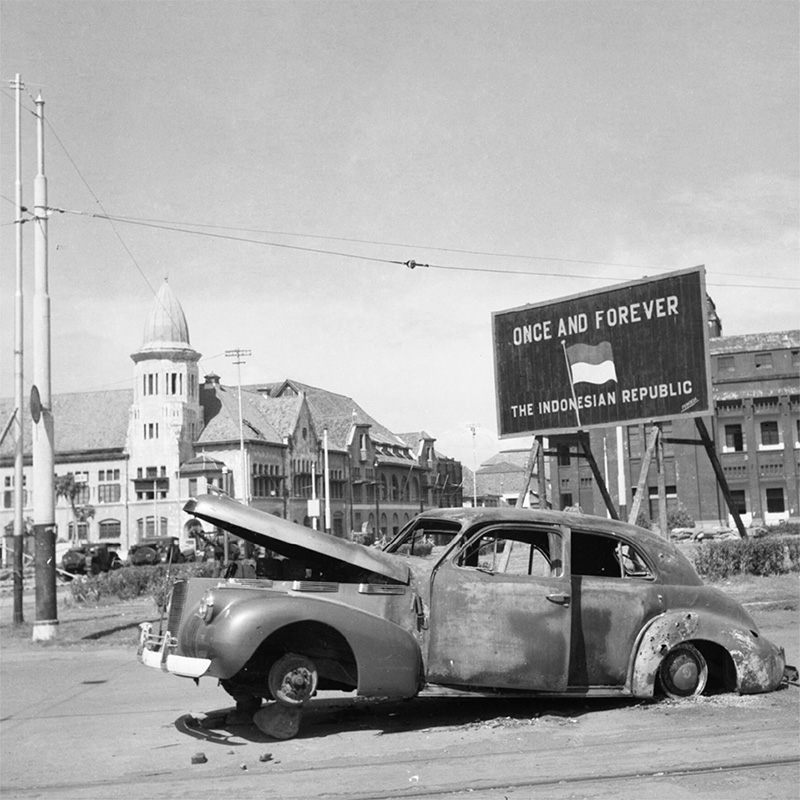

After the Japanese occupation had ended, the Indonesian independence movement renewed its efforts to oppose Dutch colonial rule.

At this time, the Netherlands was unable to muster a force sufficient to retake control. Instead, British and Indian Army troops landed on the island of Java in October 1945, tasked with reestablishing order, freeing Allied POWs and ultimately reinstating Dutch imperial authority. It turned out to be the British Indian Army's final combat deployment.

British and Indian forces would see heavy fighting there, with the city of Bandung becoming the scene of intense street battles. In addition, Japanese forces were rearmed to assist in the campaign against the Indonesian independence movement.

‘The Japanese were disarmed... and then it became apparent that the Indonesians were becoming very difficult... It got to the point where our people were having to get quite militarily tough... and in the end they rearmed some of the Japanese. The company commander would go out to a village that needed taking out and he would have a Japanese under command, and they would discuss tactics... and the Japanese company would be sent in to do it. And there would be all hell let loose upon the hill and the Japanese would return smiling and say the village is no more.’Captain Derek WT Ballance recalling his service in Java with the Royal Corps of Signals

Battle of Surabaya

The fiercest battle in Indonesia came at Surabaya in East Java. On 25 October, around 4,000 Indian Army troops disembarked at the city’s port. They were primarily tasked with evacuating Japanese soldiers and liberating Allied prisoners of war.

Upon their arrival, soldiers reported that walls across the city were daubed in slogans such as ‘Indonesia for the Indonesians’ and ‘Hand back the colonies to their rightful owners’.

Shortly afterwards, a British plane dropped leaflets over Surabaya urging all Indonesians to surrender their weapons. It angered the local population, who believed this move undermined an agreement brokered to facilitate Britain’s humanitarian mission without challenging the Indonesian independence movement.

On 28 October, a delicate truce collapsed and fighting broke out between republican militias and British forces.

Image courtesy of the IWM

The death of Brigadier Mallaby

On 30 October, with isolated groups of British Indian Army troops besieged across the city of Surabaya, the British commander Brigadier Mallaby sought to spread news of an updated ceasefire agreement.

The exact details of what happened next remain contested. Most accounts accept that Mallaby’s car approached a British outpost in the International Building near Jembatan Merah (the Red Bridge), where it encountered a large group of Indonesians (a mix of civilians and militia members). British soldiers fired into the air, prompting a panicked response from the crowd. The ensuing firefight left Mallaby and several hundred Indonesians dead.

These events sparked international outrage and further escalated the conflict.

Jewish Resistance Movement in Palestine

At the end of October 1945, following a brief lull in anti-British operations, the three major Zionist paramilitary organisations - Haganah, Irgun and Lehi - agreed to coordinate their armed opposition to Britain’s authority in Palestine.

Night of the Trains

On 31 October, the Haganah, Irgun and Lehi carried out the Night of the Trains. This was a coordinated night-time attack on the British railway network in Palestine and involved more than 150 explosions. It symbolised the founding of the Jewish Resistance Movement.

On This Day: 1945

This is the tenth instalment of a series exploring the British Army's role in 1945 – one of the most decisive years in modern history – drawing upon the National Army Museum's vast collection of objects, photographs and personal testimonies.

Throughout 2025, a new instalment will be released each month that focuses on events from 80 years beforehand. The series will highlight the everyday experiences of Britain’s soldiers alongside events of grand historical significance.