Portrait of Magdalene De Lancey, c1808

A child of the enlightenment

Magdalene Hall was born in Scotland in 1793 to Sir James Hall, 4th Baronet of Dunglass, and his wife Lady Helen (née Douglas).

Sir James was a prominent figure during the flowering of intellectual achievement in Scotland now characterised as the ‘Scottish Enlightenment’, and made notable contributions to the fields of geology and architecture.

Raised on her father’s estate in Haddingtonshire (now East Lothian), Magdalene and her nine siblings were fortunate to enjoy a privileged childhood within a loving family who encouraged intellectual pursuits.

Family misfortune

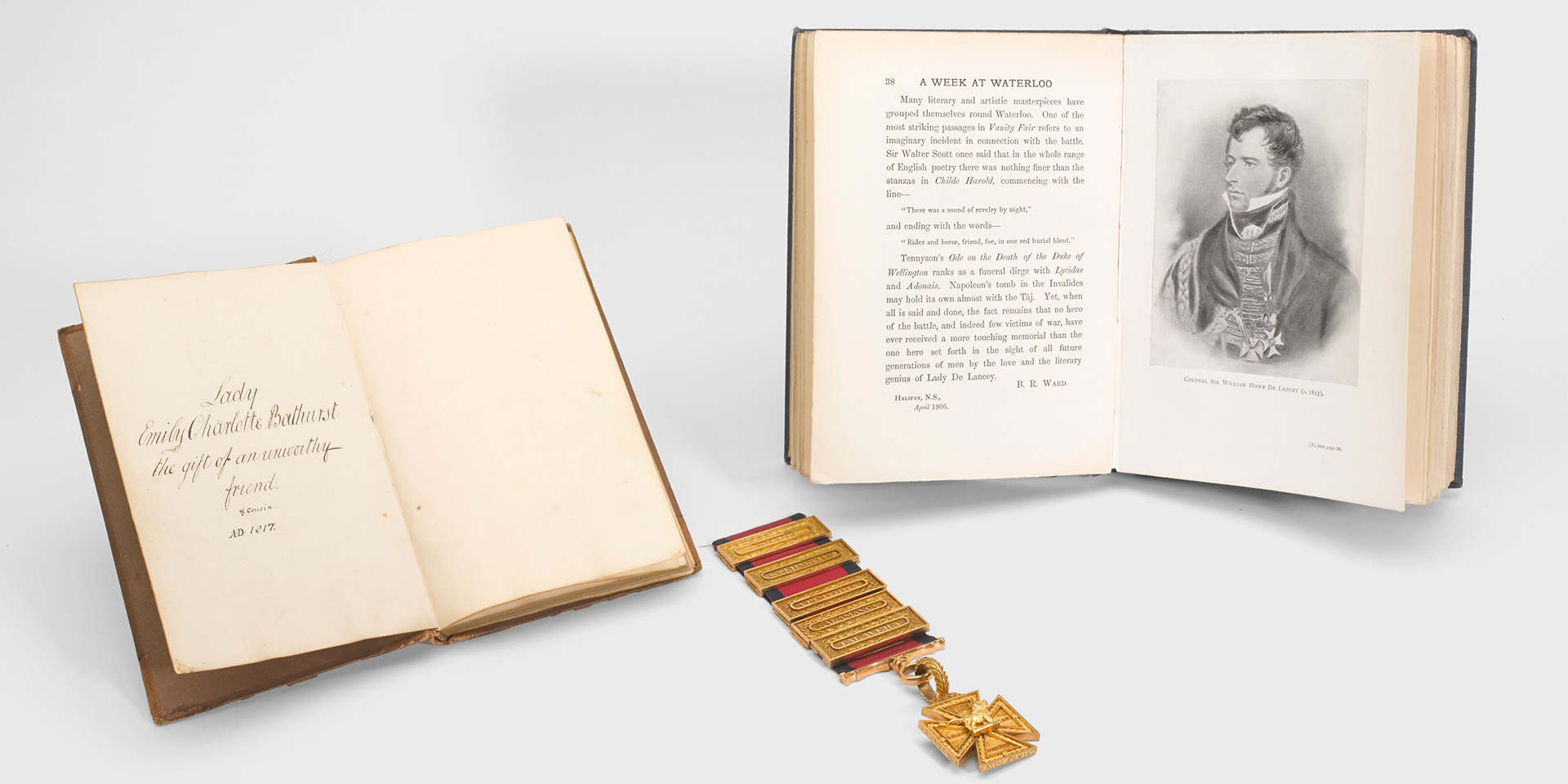

Sir William Howe De Lancey - Magdalene’s future husband - was born around 1778 into a prominent New York family of French Huguenot origin.

The De Lanceys fought for the British Crown during the American War of Independence (1775-83). Following the British defeat, they suffered greatly, losing much land and wealth. In the wake of this misfortune, William and his family moved to England to begin their life anew.

Portrait of Colonel Sir William Howe De Lancey, c1814

Regimental soldier

Continuing his family’s military tradition, William was commissioned into the British Army in 1792, aged just 14 or 15.

The following year, war broke out with Revolutionary France. This conflict evolved into a struggle against Napoleon Bonaparte and his burgeoning French Empire that would engulf Europe for more than 20 years.

In the decade that followed his enlistment, William undertook wide-ranging foreign service, including an ill-fated campaign in the Netherlands and a posting that took him to India and South-east Asia.

Professional staff officer

In 1802, William seized an opportunity to advance his career by becoming one of the first officers to take up staff training at the newly established Royal Military College (now the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst).

Through this qualification, he went on to hold a variety of quartermaster-general posts in the armies of Sir John Moore and Sir Arthur Wellesley (later the 1st Duke of Wellington) in Spain and Portugal during the Peninsular War (1808-14).

Responsible for many aspects of military planning and logistics, William became one of Wellington’s most trusted staff officers and was highly decorated for his service.

A whirlwind romance

Following Napoleon's defeat in 1814, William was posted to Edinburgh. That autumn, he met and fell in love with Magdalene. Their passion for each other must have been intense as they were married after just a few months, on 4 April 1815. However, their time together would prove short.

In March 1815, after escaping from exile on the island of Elba, Napoleon seized power in France once more. And William, just weeks after his wedding, was summoned to serve under Wellington for another campaign in continental Europe.

The calm before the storm

Desperate to avoid being separated so soon after their marriage, Magdalene followed her husband to Brussels (in today's Belgium), where an Allied force was assembling. It is here that the narrative she later wrote begins.

Arriving on Thursday 8 June, her account reveals that the couple’s time in Brussels was a brief period of bliss. They were billeted in a fine house and, with William initially only on light duties, were able to enjoy their time together.

‘I never passed such a delightful time, for there was always enough of very pleasant society to keep us gay and merry, and the rest of the day was spent in peaceful happiness. Fortunately, my husband had scarcely any business to do, and he only went to the office for about an hour every day. I then used to sit and think with astonishment of my being transported into such a scene of happiness, so perfect, so unalloyed, feeling that I was entirely enjoying life, not a moment was wasted. How active and how well I was! I scarcely knew what to do with all my health and spirits.’Magdalene De Lancey recounting her time in Brussels prior to the Waterloo campaign

A melancholy mobilisation

These halcyon days came to an end on Thursday 15 June, when the news came that the Army would be called into action. William immediately threw himself into his work, leaving Magdalene anxious and alone with her thoughts.

She was in no mood to attend the famous ball held by the Duchess of Richmond, which took place that night, but recorded that ‘many officers danced and then marched in the morning’.

Her sense of foreboding was only heightened as she watched the regiments depart the next day.

‘It was a clear refreshing morning; the scene was very solemn and melancholy, the fifes playing alone, and the regiments one after another marched past, and I saw them melt away through the great gate at the end of the square. Shall I ever forget the tunes played on the shrill fifes and the buglehorns which disturbed that night?’Magdalene De Lancey recounting the Army’s march from Brussels — 16 June 1815

An anxious wait

The couple had agreed that Magdalene would go to Antwerp on the outbreak of hostilities, where she would be safer and able to escape by sea in the event of a British defeat. There, she endured an anxious wait for news of the fighting, which was now imminent.

‘I cannot describe the restless unhappy state I was in; for it had already continued so much longer than I had expected that I found it difficult to keep up my spirits, tho’ I was infatuated enough to think it quite impossible that he could be hurt.’Magdalene De Lancey recounting her anxiety as she awaited news of her husband during the Waterloo campaign

A mortal wound

The campaign that ensued reached its climax at the Battle of Waterloo, fought on Sunday 18 June about 15km (9 miles) south of Brussels.

Although the British and their allies were ultimately victorious, the cost in life was such that Wellington was famously to lament that ‘nothing except a battle lost can be half so melancholy as a battle won’.

Wellington and his entourage were frequently exposed to enemy fire as they roved about the battlefield. De Lancey was one of many casualties among the staff officers, being struck on the back by a cannonball.

The blow was so severe that the Duke reported him dead. However, De Lancey was not killed outright. He lived on for over a week, spending his last days in a humble cottage in the nearby village of Mont St Jean.

‘De Lancey was with me, and speaking to me when he was struck. We were on a point of land that overlooked the plain. I had just been warned off by some soldiers… when a ball came bounding along en ricochet, as it is called, and, striking him on the back, sent him many yards over the head of his horse. He fell on his face, and bounded upwards and fell again. All the staff dismounted and ran to him, and when I came up he said ‘Pray tell them to leave me and let me die in peace.’The Duke of Wellington recounting the wounding of William De Lancey at Waterloo

Waterloo scene featuring the wounded De Lancey (bottom right) (Image courtesy of the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam)

A dreadful journey

In the days that followed, Magdalene would be tormented by conflicting reports of her husband’s fate. The confusion caused her to begin, end, and then recommence a journey to Waterloo to find him.

Her mental distress was compounded by the hazards of travel. In the aftermath of the fighting, the roads were chaotic and dangerous. A particularly fraught encounter arose when her party tried to pass a wagon blocking the road. A Prussian officer accompanying it attempted to wound her servant and then her horses, and only desisted when Magdalene made a piteous plea for mercy.

On approaching Waterloo, the evidence of the recent battle was overwhelming. The reek of gunpowder spread for miles and Magdalene recorded how the horses ‘screamed at the smell of corruption, which in many places was offensive’.

‘We at last left Antwerp; but bribing the driver was in vain, it was not in his power to proceed; for the moment we passed the gates, we were entangled in a crowd of waggons, carts, horses and wounded men, deserters, and all the rabble and confusion, the consequence of several battles.’Magdalene De Lancey recounting her journey to Waterloo

Bedside nurse

Arriving on Tuesday 20 June, Magdalene was greatly relieved to find William still alive. For the next week, she stayed by his bedside day and night, comforting him and ministering to his needs.

Though mainly internal, William’s injuries were obviously severe. He was attended daily by Army surgeons, who initially held out some hope of his recovery. Despite her lack of medical training, Magdalene soon became adept at assisting them.

However, the treatments prescribed - which included bleeding and the application of leeches - proved entirely ineffectual, and it soon became apparent that William’s injuries would prove fatal.

A fond farewell

Recording their final moments together, Magdalene wrote: ‘I sat down with my husband, and took his hand; he said he wished I would not look so unhappy – I wept – and he spoke to me with so much affection. He repeated every endearing expression – he bade me kiss him – he called me his dear wife’.

Of the moment of his death, she recalled that ‘he gave a little gulp, as if something was in his throat – the Doctor said “Ah poor De Lancey is gone” – I pressed my lips to his and left the room'.

Burial

On her departure, Magdalene reflected on all she had experienced, not only her great suffering but also the happiness she had been privileged to enjoy.

William was buried in a cemetery near Brussels on 28 June. Magdalene returned there a week later, noting with sadness that the date was exactly three months since their marriage.

‘Since that time I have suffered every shade of sorrow – but can safely affirm, that except the first few days, I have never felt that my lot was unbearable – while it lasted – and I believe that are not many who after a long life can say that they have felt so much of it.’Magdalene De Lancey reflecting on her experiences during the Waterloo campaign

A literary masterpiece

The following year, Magdalene wrote an account of her experiences at Waterloo. She produced both a long version and an abridged version, copies of which were circulated among her friends and relatives.

Mindful of the calibre of Magdalene’s writing and the emotive power of her story, her brother Basil later lent copies to both Sir Walter Scott and Charles Dickens, two of the great literary figures of the age. Both writers were impressed by her work.

In correspondence with Basil, Scott noted: ‘I never read anything which affected my own feelings more strongly.’

In a similar letter, Dickens was even more effusive, writing: ‘To say that reading that most astonishing and tremendous account has constituted an epoch in my life—that I shall never forget the lightest word of it—that I cannot throw the impression aside, and never saw anything so real, so touching, and so actually present before my eyes, is nothing.’

Despite its quality, the full version was not published until 1906. The book is still regarded as a great work of literature and an important testament to the tragedy of war. The original manuscripts were thought lost for many years, but the full version was rediscovered by one of Magdalene’s descendants in 1999.

The book is freely available to access via the Internet Archive.

Published edition of ‘A Week in Waterloo’, together with National Army Museum’s manuscript copy

A curious connection

One of the contemporary manuscript copies is held by the National Army Museum. Although incomplete, it has an intriguing history.

It was presented to Lady Emily Bathurst in 1817, the gift of ‘an unworthy friend and cousin’. The Bathurst connection is curious. A letter written from Brussels on 27 June 1815 by Lady Georgiana Lennox, daughter of the Duke of Richmond, to Emily’s sister Georgina contains criticisms of Magdalene’s conduct and character in the wake of William’s wounding and subsequent death.

This raises the possibility that the Hall family may have arranged for Lady Emily to have this copy to set the record straight and quash any ugly rumours about Magdalene that may have been circulating.

There is also evidence that this copy was read by Wellington himself. The Duke had visited William on his death bed; reading the narrative of his old comrade’s last days must have been a deeply moving experience.

You can read a digitised version of this manuscript copy online.

Another doomed love

Magdalene went on to find love once more. In 1818, she met Captain Henry Harvey, an officer of the Madras Army. The two were married the following year and embarked upon a grand tour of Europe for their honeymoon.

But her happiness was again short-lived. In 1822, aged just 29, she died while giving birth to her third child.

Access to the Archive

The National Army Museum provides public access to its library and archival collections via the Templer Study Centre. Over the coming weeks and months, we will be sharing more stories across our website and social media channels, highlighting some of the valuable personal insights these collections hold.