A poor return

This war trumpet passed into British hands in 1824 during the First Ashanti War (1823-31). It is made from an elephant tusk covered with stingray skin.

The Ashanti attributed great spiritual significance to horns in their tribal ceremonies. They also used them in battle, both to intimidate the enemy and to communicate with friendly forces.

Although a venerated artefact, the war trumpet can be considered a poor return compared to the trophy taken by the Ashanti. They secured the head of Sir Charles McCarthy, the governor of the British territories on the Gold Coast of West Africa.

‘It appears evident that though they have been blustering and threatening our forts, without any just cause, since last August, they were not prepared for war, but depended solely upon the terror of their name to bring us to seek a compromise.’Sir Charles McCarthy on the Ashanti in a letter to Earl Bathurst — 7 April 1823

War against the Ashanti

In 1821, the British Crown took over the territories on the Gold Coast (now Ghana) from the African Company of Merchants. The Company had been in decline since the abolition of the slave trade in 1807.

Brigadier-General Sir Charles McCarthy, a soldier of Irish descent, was appointed governor. He decided to resist the incursions being made from the interior by the powerful Ashanti kingdom against the more peaceable, and pro-British, Fanti who inhabited the coastal region. The Ashanti objected to British efforts to end the slave trade. They also wanted a greater share of the region's growing commerce.

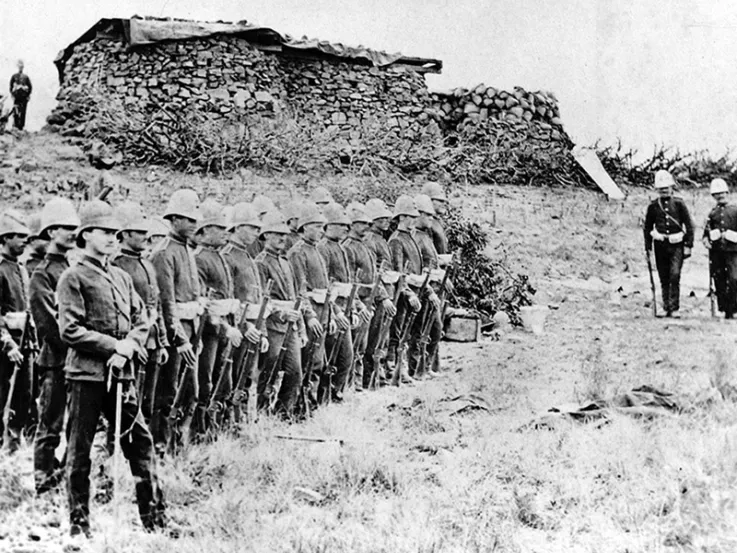

Mustering an army of Fanti tribesmen, local militia, and regulars from the Royal African Colonial Corps, McCarthy devised a strategy that would see four columns converge on the Ashanti and annihilate them.

Costly mistakes

Unfortunately, McCarthy's ambition outran his knowledge of the terrain. On 21 January 1824, his column of 500 men encountered a 10,000-strong Ashanti force at Nsamankow.

After a sporadic firefight, McCarthy’s force was soon in need of resupply. His men deserted him after the ordnance storekeeper mistakenly sent kegs of pasta up to the front line instead of ammunition.

McCarthy's fate

Wounded during the battle, McCarthy decided to take his own life rather than fall into enemy hands. The Ashanti promptly removed his head and took it back to their capital at Kumasi in triumph. It was then fashioned into a gold-rimmed drinking cup for their king.

McCarthy's skull was recovered in 1829 and interred at St Saviour's Church in Dartmouth, Devon. The British military expedition to Kumasi in 1874 later succeeded in bringing back some silver dinner forks looted from his baggage in 1824. Like the war trumpet, one of these now resides at the National Army Museum. The fork is on display in the Global Gallery.