Early years

During the late 18th and early 19th centuries, soldiers were given two meals a day. This was usually simple, slow-perishing food like salted pork or boiled beef, along with some bread. They also received a morale-boosting daily ration of a pint of wine or a third of a pint of rum or gin.

In 1811, the pioneering Donkin, Hall and Gamble company developed the vacuum tin can and the world's first factory solely for canning food. From the Napoleonic Wars (1803-15) onwards, their invention had a major impact on how food could be delivered to troops engaged in conflict. Supplies, including meat, could be preserved and protected from damage prior to consumption.

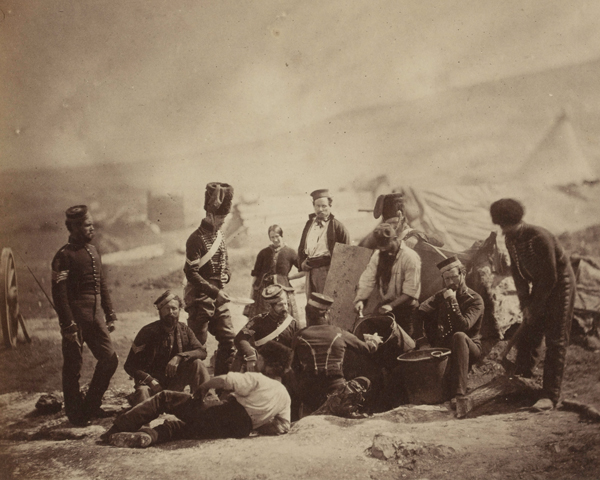

Crimean disaster

However, by the mid-19th century, despite being one of the most successful armies of the time, the British Army was unable to maintain supplies to its troops. Its transport and logistics problems during the Crimean War (1854-56) became a national scandal.

Troops in the Crimea were regularly on half rations. Biscuits and salt meat were the staples, with the monthly vegetable ration often restricted to two potatoes and an onion per man. Many soldiers developed scurvy, which led to inflamed gums, making the hard biscuits difficult to eat. In fact, more soldiers were admitted to the hospital in Scutari for scurvy than for battle wounds.

Nearly 20,000 pounds (9 tonnes) of lime juice was provided, but the newly arrived cargo was ignored. Commissary-General William Filder (responsible for supplies) felt that it was not his job to tell the troops that it was there. As a result, all 278 cases sat untouched for two months.

Hard tack

After the Crimean War, Army dietary reforms were undertaken. These focused on providing a high-energy diet for soldiers, but one that was often lacking in variety and sometimes almost indigestible.

Hardtack biscuits became a staple of soldiers' diets during the Boer War (1899-1902) and were universally loathed. The notoriously hard biscuits could crack teeth if not first soaked in tea or water!

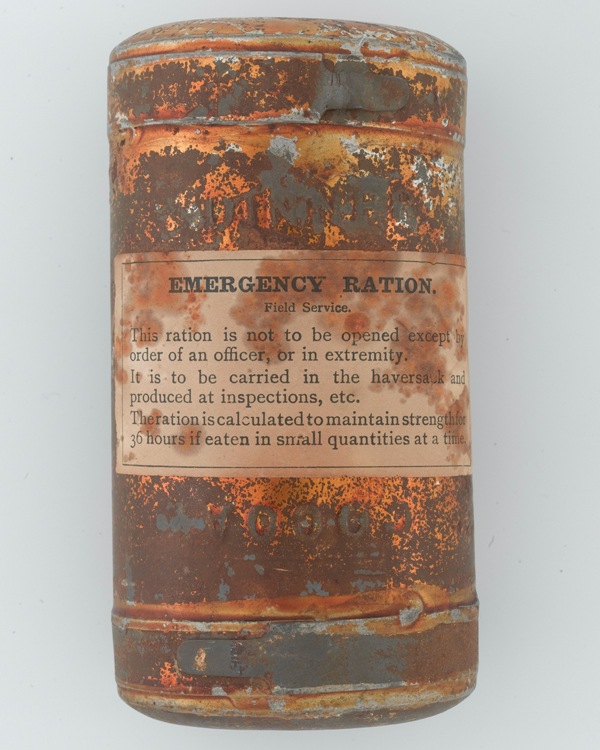

Tinned goods continued to be used to feed soldiers en masse at meal times. But the South African conflict also saw them used as 'emergency rations', given to each soldier as part of their field kit. A typical emergency ration tin consisted of a meat 'dinner' in one end and cocoa in the other. It was designed to sustain a soldier for 36 hours while on active service.

First World War

By the First World War (1914-18), Army food was basic, but filling. Each soldier could expect around 4,000 calories a day, with tinned rations and hard biscuits staples once again. But their diet also included vegetables, bread and jam, and boiled plum puddings. This was all washed down by copious amounts of tea.

The mostly static nature of the war meant food supplies were generally reliable. And soldiers were able to supplement their rations with food parcels from home, with hot meals served behind the lines in canteens and kitchens, and with food obtained from local people.

Stew

Cooking in the front-line trenches was very difficult, so soldiers ate most of their rations cold. If cooking did occur, it was done on a small folding solid-fuel stove, known universally as a 'Tommy Cooker', that many men carried in their packs. Soldiers also cooked in pots over charcoal or wood.

Usually, the men would create a stew by adding tinned meat and biscuits into the pot. When the food was ready, it would be dished out individually for men to eat from their mess tins.

As well as the endless supply of 'bully beef', soldiers grew to hate another tinned item, Maconochie's stew. Made with beef - or gristle, more commonly - and sliced vegetables, such as turnips and carrots, Maconochie was deemed edible warmed up, but revolting served cold.

On top of his regular ration issue of food, each soldier was given an emergency ration. This comprised a tin of beef, along with some biscuits and a tin of sugar and tea. This 'iron ration' was only supposed to be eaten as a last resort, when normal supplies were unavailable.

Second World War

During the Second World War (1939-45), British troops were fed freshly cooked food when in camp or barracks. On deployments, field kitchens were sometimes established. These also provided hot, fresh meals, considered vital both for nutrition and morale.

However, soldiers at the front still relied on preserved foods. These largely consisted of tinned items, but also dehydrated meats and oatmeal that were designed to be mixed with water. Morale-boosting items, such as chocolate and sweets, were also provided. And powdered milk was issued for use in tea.

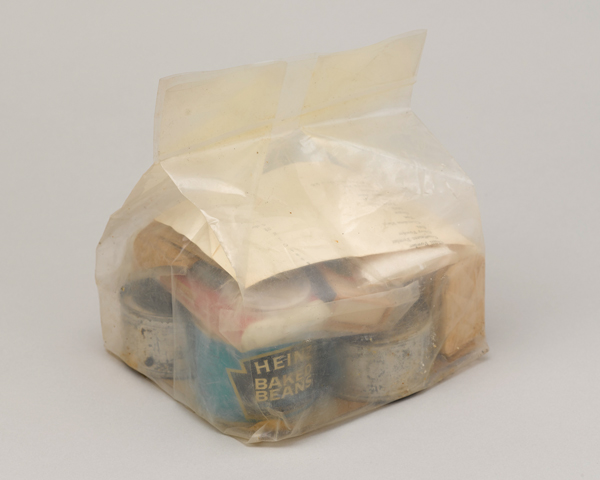

These items were packaged in 24-Hour Ration packs. They were supposed to be used by each soldier until field kitchens were set up or standard food supplies, known as composite rations, were delivered.

Also known as the 14-Man Ration, the 'compo' ration came in a wooden crate and contained tinned and packaged food. A typical crate might include tins of bully beef, spam, steak and kidney pudding, beans, cheese, jam, biscuits, soup, sausages, and margarine. Cookable items could be heated up on a variety of portable stoves.

As in the First World War, soldiers were also issued with an emergency iron ration, usually consisting of high-energy foods like chocolate.

Post-war era

Tinned rations continued to be provided after the Second World War. But as time went on, these were supplemented with packets of freeze-dried foods and products in vacuum-sealed plastic. Soldiers were supposed to be issued different menus for each day, but often ended up with the same one over and over again.

A 24-hour ration pack would contain enough calories to sustain a soldier in the field for one day. It would contain breakfast, a main meal, the ingredients to make a hot drink, and a variety of snacks including chocolate bars.

One of the more controversial changes to Army ration packs was the removal of the chocolate bars for service in Iraq and Afghanistan, as they frequently melted in the desert heat. They were replaced by sachets of peanut butter, which were significantly less popular.

By the mid-1990s, the few remaining tins were replaced with foil-packed boil-in-the-bag meals.

Diversity

The British Army has long employed overseas recruits and soldiers of every faith, so its rations have had to take these factors into consideration.

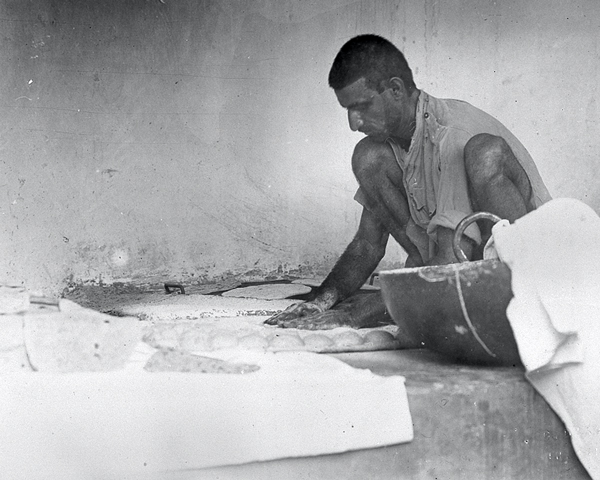

The multi-faith British Indian Army also had strict dietary guidelines when it came to feeding its troops. Two cooks, or langris, were normally maintained in each company of a battalion. The composition of the company would determine if a cook was a Muslim, Sikh or Hindu, and of what caste if the latter. This ensured that the correct food was prepared for troops of different religions and in the right way.

The Army also provided stackable cooking pots for Indian soldiers for use on campaign. Each soldier could then cook their own food if necessary. For high-caste brahmins, these cooking pots were of considerable importance, since it was necessary for them to prepare their own food in order to preserve caste.

Kitchens

During the First World War, separate kitchens were set up so that the dietary requirements of Muslim, Sikh and Hindu soldiers were met. This happened on the Western Front, as well as back in Britain.

In particular, the Indian hospital at Brighton made an effort to cater for patients’ religious and cultural needs. Muslims and Hindus were provided with separate water supplies and nine different kitchens.

Today's British Army rations continue this tradition and have a wide range of menus with halal and kosher options now available for soldiers.