Britain

Britain went to war in 1914 with a small, professional army primarily designed to police its overseas empire. The entire force consisted of just over 250,000 Regulars. Together with 250,000 Territorials and 200,000 Reservists, this made a total of 700,000 trained soldiers. Compared to the mass conscript armies of Germany, France and Russia, this was tiny.

Volunteers

Field Marshal Lord Kitchener, the Secretary of State for War, realised the conflict would be long and unprecedented in scale, so Britain would have to create a new mass army.

Thousands of eager volunteers quickly flocked to the Colours on the outbreak of war. But these men were completely untrained. They spent their first months in the Army learning the basics of soldiering.

These ‘New Armies’ faced a baptism of fire in the battles of 1915-16. Until then, the Regulars - supported by the Territorials and Reservists - took the leading role.

Conscripts

Despite the influx of volunteers, the British still needed more men. Conscription was introduced in 1916. This eventually expanded the Army to a force of over 4 million men by the end of the war in 1918.

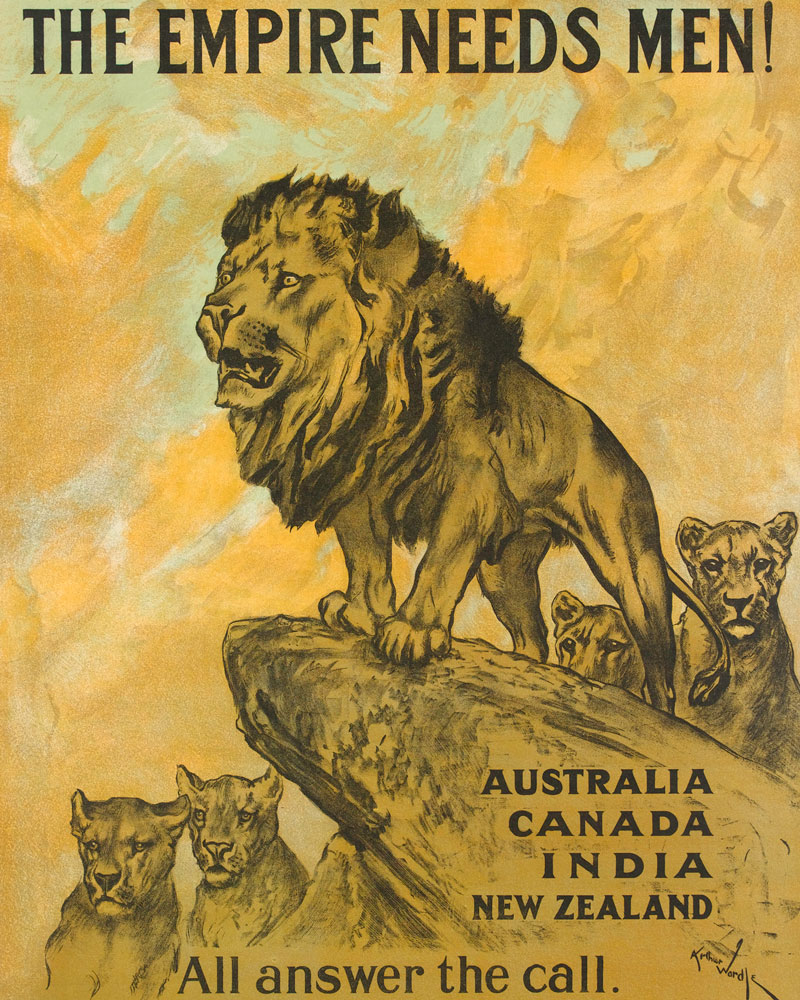

Empire

However, even an army of this scale was not sufficient to meet all of Britain’s commitments. Throughout the conflict, it was bolstered by forces from across the Empire, with each nation pledging full support for Britain following its declaration of war against Germany in August 1914.

Caribbean

Around 15,000 West Indians enlisted, including 10,000 from Jamaica. Others came from Trinidad and Tobago, Barbados, the Bahamas, British Honduras (now Belize), Grenada, British Guiana (now Guyana), the Leeward Islands, St Lucia and St Vincent.

Although a few served in regular British Army units, most men from the Caribbean served in the West India Regiment and the British West Indies Regiment (raised in October 1915), serving in France, Italy, Africa and the Middle East.

Twelve battalions of the British West Indies Regiment were raised, mainly as labourers in ammunition dumps and gun emplacements, often coming under heavy fire. Towards the end of the war, two battalions saw combat in Palestine and Jordan against the Turks of the Ottoman Empire.

India

Soldiers from the Indian subcontinent (now India, Pakistan and Bangladesh) fought in all the major wartime theatres and made a decisive contribution to the struggle against the Central Powers.

Two infantry and two cavalry divisions had arrived on the Western Front by the end of 1914. Eventually, 140,000 men saw action there.

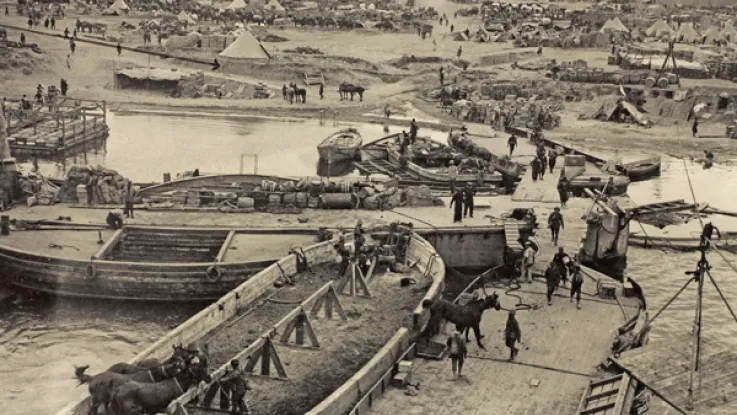

In 1915, Indian troops arrived in the Middle East, where they fought against the Ottoman Turks in Palestine and Mesopotamia (now Iraq). That same year, soldiers from the Indian Army fought alongside British, Australian and New Zealand troops on the Gallipoli Peninsula.

They also formed a large proportion of the Allied forces occupying former enemy territory in East Africa, the Balkans, Asia Minor and the Caucasus. In total 1.27 million Indians voluntarily served as combatants and labourers.

Africa

African troops played a key role in containing the Germans in East Africa and defeating them in West Africa. Europeans and Indians struggled in the harsh African climate, but the local inhabitants had the skills to survive and prosper.

By November 1918, the ‘British Army’ in East Africa was mainly composed of African soldiers. The units involved were the West African Frontier Force drawn from Nigeria, the Gold Coast (now Ghana) and Sierra Leone, and the King’s African Rifles, recruited from Kenya, Uganda and Nyasaland (now Malawi).

At least 180,000 Africans also served in the Carrier Corps in East Africa and provided logistic support to troops at the front.

South Africa

Over 60,000 labourers came from South Africa. Black South Africans were restricted to a logistical role because the South African government feared arming them. Around 25,000 black South Africans were also recruited to the South African Native Labour Contingent that served on the Western Front in 1916-17.

In 1915, an expeditionary force of 67,000 white South African troops invaded German South-West Africa (now Namibia). Many of these soldiers later fought in East Africa as well.

White South African units were also sent to the Western Front. On 14 July 1916, the 1st South African Brigade - 3,153 officers and men - entered Delville Wood on the Somme. After six days of vicious fighting in hellish conditions, only around 750 of them remained unharmed.

Canada

Following the outbreak of war, Canada raised the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) for service on the Western Front. From 1915, it fought in most of the major battles, winning renown at the Second Battle of Ypres (1915), on the Somme (1916), at Vimy Ridge (1917) and at Passchendaele (1917).

Canadian troops also played a leading role in the victorious Hundred Days offensives of 1918, spearheading many of the Allies’ key attacks. The CEF lost over 60,600 men killed during the war, nearly 10 per cent of the 620,00 Canadians who enlisted.

Newfoundland

Newfoundland, not part of Canada until 1949, also sent troops. The Newfoundland Regiment fought at Gallipoli (1915), but the following year was almost wiped out at Beaumont Hamel on the Somme. It later fought at Arras and Passchendaele in 1917 and helped repel the German Spring offensive of 1918.

Australia

Over 410,000 Australians served with the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) during the war, sustaining around 200,000 casualties.

In April 1915, Australians landed at Gallipoli in Turkey with troops from New Zealand, Britain and France. The following year, Australian forces fought in campaigns on the Western Front and in the Middle East, where they defended the Suez Canal and help take Sinai. Later they advanced into Palestine and helped capture Gaza and Jerusalem.

In 1918, the Australians played a leading role in the decisive Allied advances on the Western Front from August until the end of the war.

New Zealand

Following the outbreak of war, New Zealand forces helped Australia capture Germany's colonies in the Pacific. Almost 100,000 New Zealanders also served overseas in the New Zealand Expeditionary Force (NZEF), including 2,700 Māori and Pacific Islanders.

Around 18,000 New Zealanders gave their lives. This included 2,700 men killed at Gallipoli and over 12,000 soldiers killed on the Western Front.

As was the case with their Australian and Canadian comrades, the experience of fighting together away from home helped the NZEF’s soldiers forge a distinct national identity.