Crisis in the Caucasus

After the Bolsheviks seized power in Russia during the October Revolution (1917), the Russian armies opposing the Turks on the Caucasian Front began to disintegrate. The British therefore felt it necessary to bolster the Allied position there.

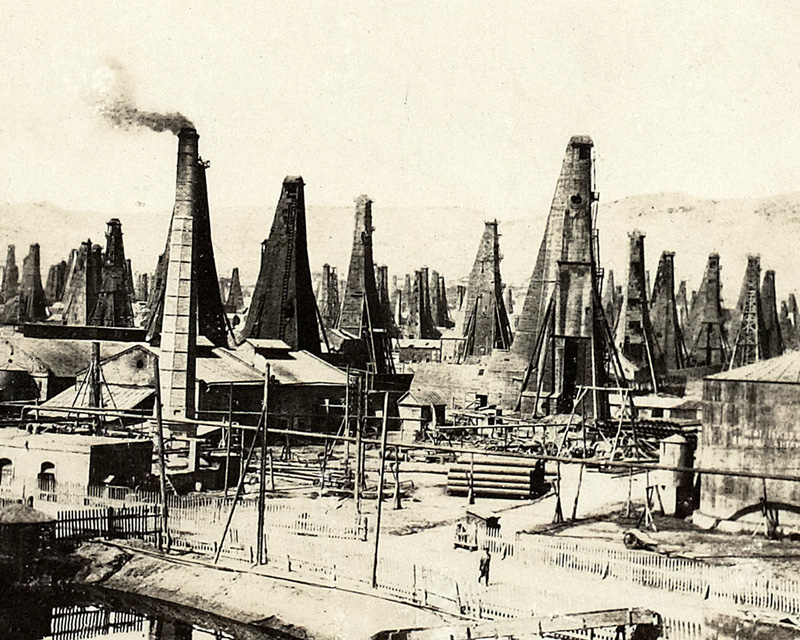

Dunsterforce, named after its commander Major-General Lionel Dunsterville, was tasked with securing the vulnerable oil installations at Baku and the strategically important Trans-Caucasian railway from both the Turks and the Bolsheviks. Such a move would also secure the right or eastern flank of the British forces fighting in Mesopotamia, now exposed following the Russian withdrawal.

Irregular army

This was all to be achieved by organising local groups of Armenians, Assyrians, Georgians and anti-Bolsheviks into an irregular army.

Dunsterville even had the authority to encourage the establishment and maintenance of independent friendly nations, such as Georgia and Armenia, in order to stabilise the Caucasus and simultaneously help safeguard the approaches to British India from any possible Turkish attack. This was deemed a real threat given Turkish intentions to expand their influence both in the Caucasus and further eastwards.

Special ability

Dunsterforce, officially called the British Military Mission to the Caucasus, consisted at its peak of around 1,000 officers and non-commissioned officers. They were selected from across the British Empire, including men serving on the Western Front and in the Middle East.

One officer wrote of an emphasis on ‘strong character, and adventurous spirit, especially good stamina, capable of organising, training and eventually leading, irregular troops’.

‘All were chosen for special ability, and all were men who had already distinguished themselves in the field. It is certain that a finer body of men have never been brought together.’General Lionel Dunsterville, ‘Adventures of Dunsterforce’ — 1920

Advance party

The men recruited from the Western Front sailed from London on 29 January 1918 and arrived in Baghdad on 20 March. But growing worries about the chaotic situation in the Caucasus had already forced the British to send ahead an advance party on 27 January.

Dunsterville and 50 other men were ordered to head north to secure Baku and then, if possible, move to Tiflis (now Tbilisi) where they were to establish a base for recruiting and directing irregular forces. They took with them a large amount of Persian silver and British gold to assist this plan.

Map of northern Persia and the Caucasus, 1918

Stopped at Enzeli

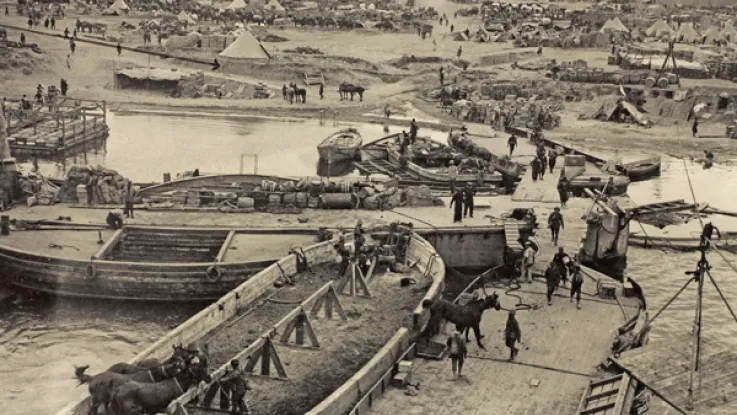

Driving cars, vans and armoured vehicles, they travelled over 300 miles north-east through difficult Persian terrain, over the 7,600-feet Asadabad Pass, down to Hamadan, and then north another 250 miles to Enzeli (now Bandar-e Anzali) on the Caspian Sea. En route, this small force was bolstered by a group of anti-Bolshevik Cossacks whom they encountered at Kermanshah.

At Enzeli they hoped to obtain ship passage to Baku. But, arriving on 19 February, they found the port controlled by hundreds of armed Bolsheviks and other revolutionaries. The message they received was that Russia was no longer at war with the Turks, and the British were not wanted there.

Hearts and minds

Dunsterville returned to Hamadan, arriving on 25 February 1918. His group now stayed there until the summer. They spent the next few months engaged in famine relief work and civil construction projects.

Many locals resented the presence of foreign soldiers in Persia as earlier depredations by the Turkish and Russian armies had contributed to widespread starvation. The Dunsterforce aid effort bolstered the reputation of the British in what was officially still a neutral country.

Dunsterforce officers also trained the locals so that they could defend their villages from bandits and Turkish-backed tribesmen. Members of the group engaged in several skirmishes with the latter and helped deny the movement of enemy agents through north-west Persia.

Urmia crisis

In July 1918, Dunsterville also sent a small force with money and arms to assist the Jelus, a group of Assyrians resisting the Turks around Lake Urmia to the north-west.

‘The Assyrians were forced to evacuate their own country in the 1915 summer. After this they were armed and are now generally spoken of as “Jelus”. We sent them thousands of rifles and much ammunition. It was very difficult to get it to them across country.’Captain William Leith-Ross — 1920

Refugees

But when the British group arrived, they found the town of Urmia captured by the Ottoman army. About 80,000 people fled and the Dunsterforce party helped hold off the Turkish pursuit and attempts by Muslim Kurdish tribesmen to attack the refugees.

Eventually they reached safety near Hamadan, where a brigade-sized force was later raised from the survivors, trained and commanded by a small Dunsterforce detachment. The remaining Assyrian refugees were sent on to refugee camps near Baghdad.

During this episode, the British found it difficult to work out who among the myriad tribes and faiths in the region were allies or enemies.

To Baku

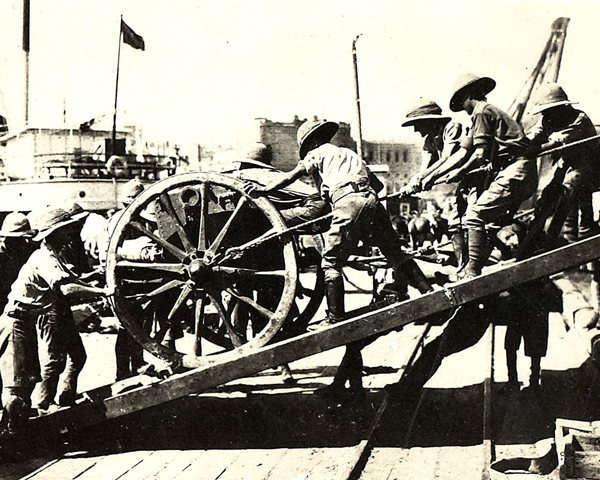

During May-June 1918, the London contingent and extra infantry and cavalry detachments had joined Dunsterville at Hamadan. They had travelled from Baghdad by train part of the way before being forced to march with mules the remaining 200 miles.

Now re-inforced, Dunsterville returned to Enzeli, which was finally occupied on 27 June. He then set sail for Baku in early July.

Under siege

By the time Dunsterville disembarked in Baku, the city was already under siege by the Turkish army. For the next six weeks, his men struggled to bolster the 7,000 Armenian, Assyrian and Russian volunteers (including some Bolsheviks) defending the port.

Factions

Dunsterforce tried training the troops into an army, but found them commanded by five different political factions. This made control and co-ordinated action difficult.

More British reinforcements arrived, including troops from 39th Infantry Brigade and two Royal Air Force Martinsyde fighter-bombers. But the local forces frequently melted away when attacked or failed to follow orders. The British also witnessed local Armenian women fighting in the trenches.

‘There were many women who did this, for they had lost their homes and had nowhere else to go. They preferred to take their chances with their own men, rather than remain behind unprotected.’Captain William Leith-Ross — 1920

Offensives

On 1 September 1918, large Turkish regular forces and Muslim tribesmen launched co-ordinated offensives against both Baku and Hamadan. Baku fell on 14 September.

Dunsterville evacuated his force back to Enzeli and then Hamadan, leaving 180 soldiers dead or captured. He was accompanied by thousands of Armenian refugees.

Disbandment

Luckily, the Turks greatly overestimated Dunsterforce’s strength. Once it was back in northern Persia, they suspended their drive from Tabriz towards Hamadan. This provided some security to the right flank of the British forces in Mesopotamia, which had been one of the original goals of the mission.

The War Office disbanded Dunsterforce on 22 September 1918. Most of the surviving men returned to their original units.

Analysis

The resources available to Dunsterville, both in terms of men and equipment, were insufficient to accomplish the mission’s main goals of holding oil-rich Baku before advancing to Tiflis or securing the railway network. The British also struggled to mobilise the residents of Baku, who were too pre-occupied with infighting to mount a united defence.

Despite this, Britain’s wartime prime minister, David Lloyd George, believed Dunsterforce succeeded in keeping the Ottomans and Germans from acquiring much-needed oil for six crucial weeks in August and September 1918. This was a period in which the war was decided by victories over Germany on the Western Front, and defeats of the Ottomans in Mesopotamia, Palestine, and Salonika.

On 30 October 1918, the Ottoman Empire signed the Armistice of Mudros with the Allies, so its occupation of Baku and the oilfields was short lived.

Special Force

They may not have achieved all their objectives, but the men of Dunsterforce exhibited the kind of courage and endurance we often associate with Special Forces missions.

In northern Persia and the Caucasus, the conditions in which they travelled and fought were extreme. Marches of up to 30 miles per day in temperatures topping 50C, or plummeting to -40C in the mountain passes, were routine.

They were cut off from immediate re-inforcements and lacked a reliable supply line. It also took great skill to drive and maintain a column of basic motor vehicles across such terrain.

The men of Dunsterforce were often treated as unwelcome strangers in lands wracked by famine, war, genocide, and civil unrest. But they tried to work with local groups against a common enemy.