Warning: This story contains some graphic images.

Negotiations

In early April 1945, General Sir Evelyn Barker’s VIII Corps was advancing north-eastwards across Germany towards the Baltic. Word had arrived that the Germans were looking to call a local truce. On 12 April, a German emissary was brought into the corps headquarters to negotiate the terms.

Among the British troops closest to this area were the soldiers of 11th Armoured Division. They had crossed the River Weser on 5 April with 270 tanks and were closing on the city of Lüneburg, aiming for the River Elbe and advancing across the woodland and heather of the Lüneburg Heath.

Truce

On the division's line of advance lay a camp at a place called Belsen. The German envoy explained that diseases such as typhus were endemic there. His plan was to declare it an open area, thereby avoiding any fighting that might allow the inmates to escape and spread disease to soldiers of both sides as well as local civilians.

Reconnaissance, including Special Air Service patrols and groups from 20th Armoured Brigade, had verified the camp’s presence. The truce was accepted, and on 12 April a 48-square-kilometre exclusion zone was placed around the camp, and the area declared neutral. No shots would be fired in its vicinity.

The Germans, and the Hungarians they were employing, would remain only to guard the camp until the British arrived. After that, they would be allowed to march back to their own lines with their weapons.

A camp in the woods

On 15 April, three days after the truce, and with strong German resistance continuing in the area around the neutral zone, the first British troops entered the camp. These were from 63 Anti-Tank Regiment, Royal Artillery, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Richard Taylor.

Together with a loudspeaker truck from the Intelligence Corps commanded by Lieutenant Derrick Sington, a journalist in civilian life, they made their way down roads that led away from nearby villages and deep into the woods. They were utterly unprepared for what they found.

There were more than 60,000 emaciated prisoners in desperate need of sustenance and medical attention. Worse still, 13,000 corpses lay around the camp, unburied and rotting. Despite being experienced soldiers familiar with the horrors of war, they had never encountered anything like this.

The most horrific conditions

As well as many Jews, the camp contained a cross-section of those the Nazis deemed inferior and enemies of their state. There were 20 nationalities altogether, in the most horrific conditions. Many had been marched from camps further east and then simply dumped at Belsen by their captors. Additionally, there was a Soviet prisoner-of-war camp attached, the inmates of which were also in an appalling state.

Veteran BBC journalist Richard Dimbleby, accompanying the troops, produced a radio report based on what he saw. Initially, his superiors in London refused to believe it and would not broadcast it. Only after he threatened to resign did they relent. Dimbleby stated, ‘This day at Belsen was the most horrible of my life.’

British response

Despite still being at war, the British took on the humanitarian crisis. Emergency medical aid was organised under the direction of Brigadier Glyn Hughes. Attempts were made to clean up the camp by burying bodies and implementing a form of quarantine to prevent the further spread of disease among the weakened population.

Aiding the living was a major task. By the end of 16 April, 27 water carts had been provided, along with enough food for an evening meal, all delivered by VIII Corps. But it was not simply a case of handing out the food. In fact, the Army rations had a negative effect on the weakened prisoners - their malnourished bodies could not cope as the food was so much richer than what they were used to.

The prisoners’ health needed to be monitored, and their diets steadily improved; a special gastric diet for those on the verge of starvation was implemented, adapted from the experience of the Bengal Famine in 1943. Limited amounts of milk, sugar and water were given, either by medical volunteers from Britain who had arrived on 29 April, or by those internees strong enough to feed themselves and others. Despite these efforts, a further 14,000 people died after the camp's liberation.

British soldiers supervise the distribution of food to camp inmates, April 1945 (© IWM BU 4242)

Assistance

The surviving internees were stabilised, deloused and moved to the nearby tank training barracks at Bergen-Hohne, which became a Displaced Persons (DP) camp. The Round House there, which would become so significant for the British after the war, was used as a hospital. In Bergen-Hohne, the internees were registered, medically treated, clothed and prepared for repatriation. Within four weeks, 28,900 people had been moved.

Throughout this time, the Army also had to organise the burial of those prisoners who had died of disease or starvation – 15,000 in total. The Hungarians and SS guards still on the site, along with other German prisoners of war, were made to help. Civilians, including the local council of the city of Celle, were also forced to visit the camp and see it for themselves.

Burning

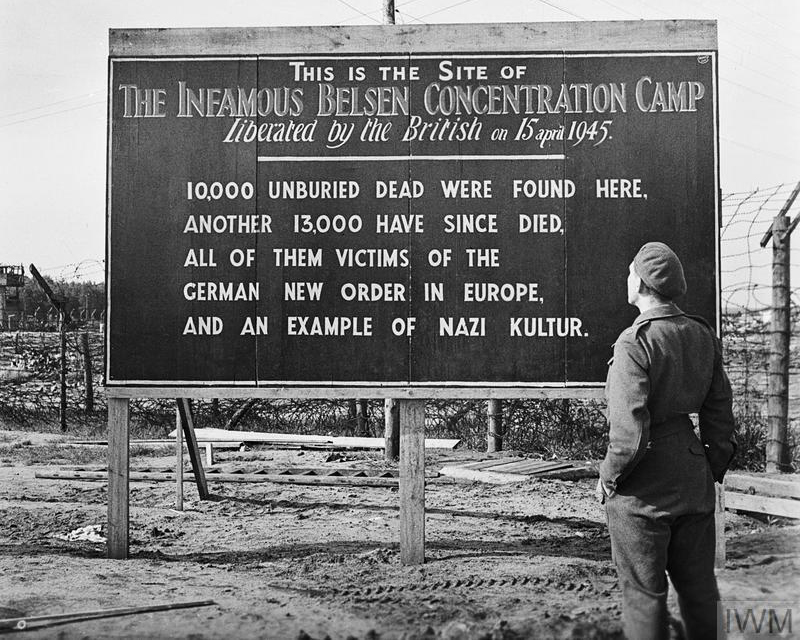

On 21 May 1945, once the last prisoners had been moved and the last casualty buried, the camp accommodation huts were burned to the ground. Outside the camp, the British put up signs in English and German to mark the scale of what had been done. One of the signs was soon stolen.

Yet back in Britain, and even among some sections of the Army, there was doubt that what had been reported from Belsen was true. It was just too far beyond comprehension. Some claimed it was only propaganda, and fake news. This motivated many soldiers to visit and see it for themselves.

A sign erected by the British at Belsen's entrance, May 1945 (© IWM BU 6955)

‘Why did I visit Belsen? Given the opportunity I went because I know that in a few years’ time only, clever people will say, “Nonsense! Don’t you realise that was just wartime propaganda?” I shall know how to reply. And the more who do the better for the peace of the world.’‘Belsen Concentration Camp – the Final Degradation, by a Military Observer’ — April 1945

‘Never goes away’

Belsen was not a death camp like those the Red Army discovered on their advance from the east. Rather than an organised system of murder, it was designed to cause death by neglect. But the scale of the atrocity still horrified those who saw it.

Sergeant Owen Smart recalled:

‘Before we entered the camp I had never heard of Bergen-Belsen. I knew nothing of what had been going on. We heard about atrocities, which are bantered backwards and forwards, but we didn’t realise really what it was, and then it was just after that, that all the rest of it came about, other camps just like Belsen.

'But to me the name Belsen after that was shocking. I didn’t see anything of the inmates in the prison really. I saw a few, possibly the remainders of those that were fit enough to be put into a hospital – but I didn’t see many of the actual people. They had been taken away, or the remains of them. That was awful... There’s no doubt that after seeing something like what had gone on in Belsen, it does stay in your mind and never goes away.’

Attitudes

Word of Belsen quickly spread around the wider Army. As well as appearing in the national press and passing as gossip, it featured in 'Soldier' magazine. It was the first concentration camp encountered by the British and instantly influenced attitudes towards the local Germans. While many soldiers had expressed sympathy for the plight of ordinary Germans as they moved through their shattered towns and cities, Belsen led to a hardening of feeling.

There was great suspicion that the locals in towns like Bergen, only a few kilometres from Belsen, must have known what was happening there, despite their protestations to the contrary. At a time when British soldiers were increasingly coming into contact with local Germans, it undoubtedly affected interaction.

The reckoning

The British began investigating what had happened at Belsen immediately after the liberation of the camp. Later, a special military tribunal was convened between 17 September and 17 November 1945 in Lüneburg. It tried 44 men and women who had worked at Belsen.

Eleven of the defendants were sentenced to death, including commandant Josef Kramer, head female guard Elisabeth Volkenrath, and camp doctor Fritz Klein. They were executed in Hamelin in December 1945.

More than a hundred international journalists had reported on the trial and broadcast the evidence to the wider world. Personnel serving in the British occupation zone were able to watch the trial from the public gallery.

Major Winwood, Josef Kramer's defence, addresses him at the trial, September 1945 (© IWM AP 281835)

Later years

After the war, the British were faced with the task of administering and rebuilding their occupation zone. As part of this, they maintained a military presence at Bergen-Hohne, on the doorstep of the Belsen camp. It lasted for the next 70 years. The camp itself became a memorial, and a site often visited by British soldiers stationed in Germany.

The Army’s relationship with the local Germans also improved. On 14 November 2014, 7th Armoured Brigade, the famous 'Desert Rats', held their last parade as an armoured brigade ahead of their transformation into 7th Infantry Brigade, with 640 soldiers marching through Bergen. The brigade was presented with a 'Fahnenband' by the local German military commander on behalf of his nation, marking a long period of friendship.

7th Armoured Brigade’s commander, Brigadier James Woodham, called it an occasion ‘to celebrate a fantastic history that has been based here in Germany since the end of the Second World War and to thank our German hosts who have been so fantastic at looking after us’. The 'Desert Rats', who had been headquartered in Germany since 1945, left for the UK the following year when Bergen-Hohne finally closed.

The British Army link to that area, which had begun in tragedy 70 years earlier, was brought to an end in a state of friendship. But the horror of what was endured at Belsen will never be forgotten.

The site of the camp is now a memorial to those who died between 1940 and 1945, 2018 (© Peter Johnston)

The silence of this place / Where no birds sing, / This pit of hell, where trees enshroud / As walls, to hide the shame. / These tragic mounds of earth, / Each one marked with symbolic death, / ‘Here lie five thousand dead’, / Just that, no more. / Theirs was no thrilling battle-cry, / No bugles sounding the night / Quickened their breath, or touched their souls / To challenge immortality. / Only the whispers of the winter leaves, / The soft pale whispers on the lips of death. / Blown by the wind across our feet. / The earth is wet with tears, / Making dark rivers in these paths of mud / There stands their shrine, these nameless ones / A lonely finger pointing to the sky / The conscience of the world in sallow stone, / The sorrow of the world, written in blood.Anthony Rawlings, who visited the Belsen site while serving in the area with 7th Armoured Division — 1951