State of affairs

By November 1945, it was abundantly clear that the peace ensuing from the Second World War was at best fragile and, in some instances, vulnerable to collapse.

In Palestine, the British Army confronted an escalating conflict between two rival nationalist movements – Jewish and Arab. The British government’s decision to maintain wartime restrictions on Jewish migration from Europe further inflamed the conflict. In response, the increasingly militant Zionist movement launched a series of terror attacks against British rule.

British and Indian soldiers remained on active duty in Southeast Asia. The British response to the death of Brigadier Mallaby in Java at the end of October escalated into a major battle with Indonesian nationalists in the city of Surabaya. Yet Britain’s rapid military success did not signal the end of the Indonesian National Revolution. Instead, the fighting now spread to the rest of the island of Java, and soon across the entire country.

Elsewhere, the challenging legacies of the Second World War were highlighted in the courtroom. In Germany, the sentencing of the Belsen trial saw Nazis brought to justice for the first time. A few days later, the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg began its prosecution against the most senior surviving members of the Third Reich.

Meanwhile, the first trial of Indian National Army (INA) soldiers began in Delhi. INA troops had fought alongside the Japanese during the war, but were also held up as emblems of the Indian independence movement. Their conviction for ‘waging war against the King’ inspired violent protests against the continuation of British rule in India.

Anti-Jewish riots in Tripolitania

5-7 November 1945

From 1943 to 1951, the Libyan regions of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica - formerly colonised by Italy - were occupied by British troops as part of an Allied administration. France was responsible for the southern region of Fezzan.

Under Italian fascist rule, Libya’s substantial Jewish community had experienced antisemitic oppression. After the Allied liberation in 1943, there was some improvement in their circumstances, but their future remained uncertain.

On 5 November 1945, anti-Jewish riots broke out among the majority-Muslim population of Tripolitania. In the city of Tripoli, over 140 Jews were killed and hundreds more injured.

The formation badge of the British force in Tripolitania is pictured above.

Growing crisis in Indonesia

Following the death of Brigadier Mallaby in October, Indonesian militias continued to fight against British and Indian troops in Surabaya, East Java.

On 8 November, British commander General Sir Robert Mansergh ordered all Indonesians to disarm within two days or face ‘all the naval, army and air forces under my command’.

This call was rejected while the political figurehead of the Indonesian independence movement, Sukarno, urgently appealed to both President Truman and Prime Minister Attlee to intervene and so prevent further bloodshed.

Battle of Surabaya

Following the refusal of Indonesian regular and irregular fighters to disarm, additional British troops arrived in Surabaya. On 10 November, they began a counter offensive in the city.

This was the most intense battle of the entire revolution, with at least 6,000 Indonesian and 295 British casualties. 10 November is now an official day of remembrance in Indonesia, celebrated as Heroes' Day.

British Indian Army troops are pictured above taking part in the wider fighting.

By land, sea and air

A bombardment of the Surabaya coastline from two cruisers and three destroyers of the Royal Navy, as well as relentless bombing from the Royal Air Force, supported the advance of 20,000 British Indian troops.

The assault overwhelmed the Indonesians, most of whom were lightly armed civilian guerrillas. Within three days, much of Surabaya had been recaptured. By the end of the month, the battle was won.

However, the Indonesians' fierce resistance continued. Many independence fighters fled to the countryside, where they inspired a more general revolt that rapidly spread across the rest of Java.

‘As we drew near we wondered what the situation was like, for there was a good deal of gunfire; the night was pitch black except for three very large fires which flickered across the water, making everything seem unreal, for when a country is at war one expects to be placed in positions such as this, but the war was finished long ago, and it was difficult to realise that here, in Java, armed warfare was still being raged.’Matron Winifred Aldwinckle describing the work of the 82 Indian General Hospital, Surabaya, Indonesia — November 1945

Britain and the Indonesian Revolution

British military commanders and politicians were concerned at the ferocity of the fighting in Surabaya and the growing prospect of a full-scale war. But, for the time being, the campaign against Indonesian nationalists continued.

Over the following months, Britain’s forces fought street battles in cities across Java, including Semarang, Magelang and Bandung. However, plans were soon in place for newly trained Dutch troops to relieve the British Indian soldiers there. In the picture above, Dutch and British flags fly side by side on the roof of an official building.

By November 1946, when the last British forces left Indonesia, almost 1,000 British and Indian soldiers and over 20,000 Indonesian civilians and combatants had lost their lives. Dutch troops continued their colonial war until eventually conceding defeat. Indonesia was granted unconditional sovereignty in 1949.

Award for service in Java

This General Service Medal with a ‘S.E. Asia 1945-46’ clasp is the only official award for service during the Indonesian campaign.

In terms of casualty figures, this stands as the fourth largest British military campaign since the end of the Second World War.

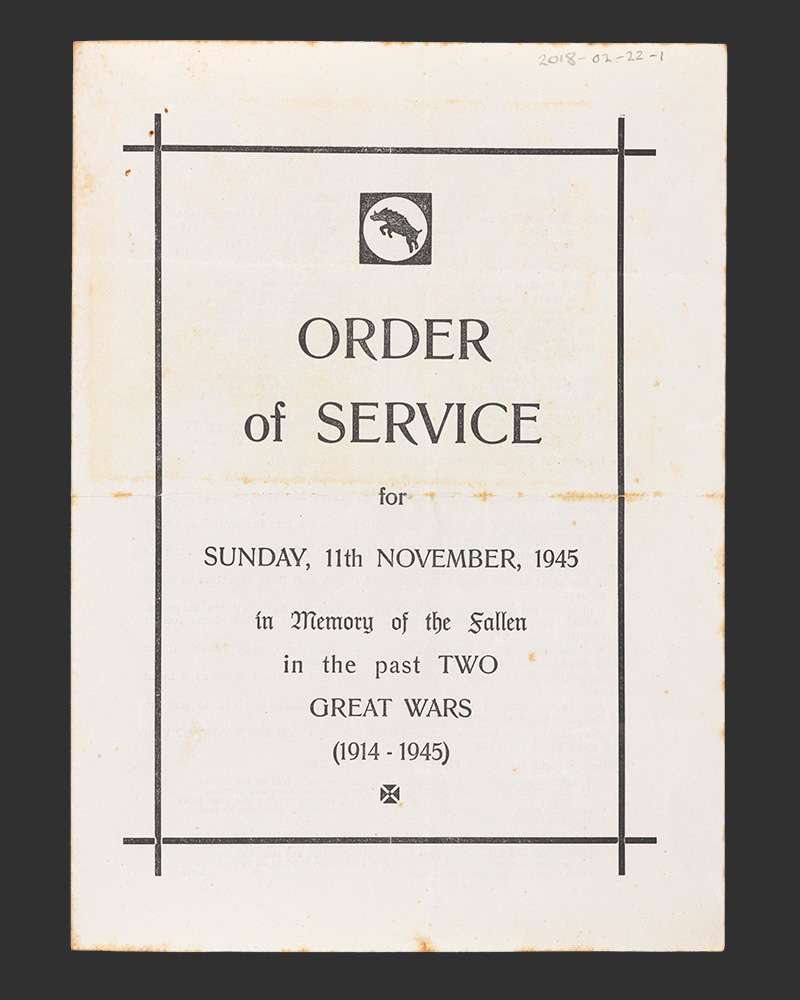

Remembrance Sunday

11 November 1945

Sunday, 11 November 1945 marked the first Armistice Day since the end of the Second World War.

At the outbreak of the conflict in 1939, the British government had paused large-scale commemorations and the annual two-minute silence was no longer honoured. Six years later, the tradition was reinstated with British soldiers and civilians taking part in poignant ceremonies. An order of service from a remembrance ceremony held by XXX Corps in Germany is pictured above.

From 1946, the traditional two-minute silence was moved from 11 November to the second Sunday of the month, known as Remembrance Sunday. This was a formal means of honouring the fallen of both World Wars in a single ceremony.

In 1995, the silence at 11.00am on 11 November was reintroduced. It continues to be observed alongside Remembrance Sunday each year.

‘We found the Danes very friendly & hospitable & they speak good English & have an outlook very like or own. I realized the other day that I now have the record of having been to a different European capital each month for the last 6 months.’Junior Commander Margot Marshall, Auxiliary Territorial Service, writing to her mum from Copenhagen, while on leave from Germany — 11 November 1945

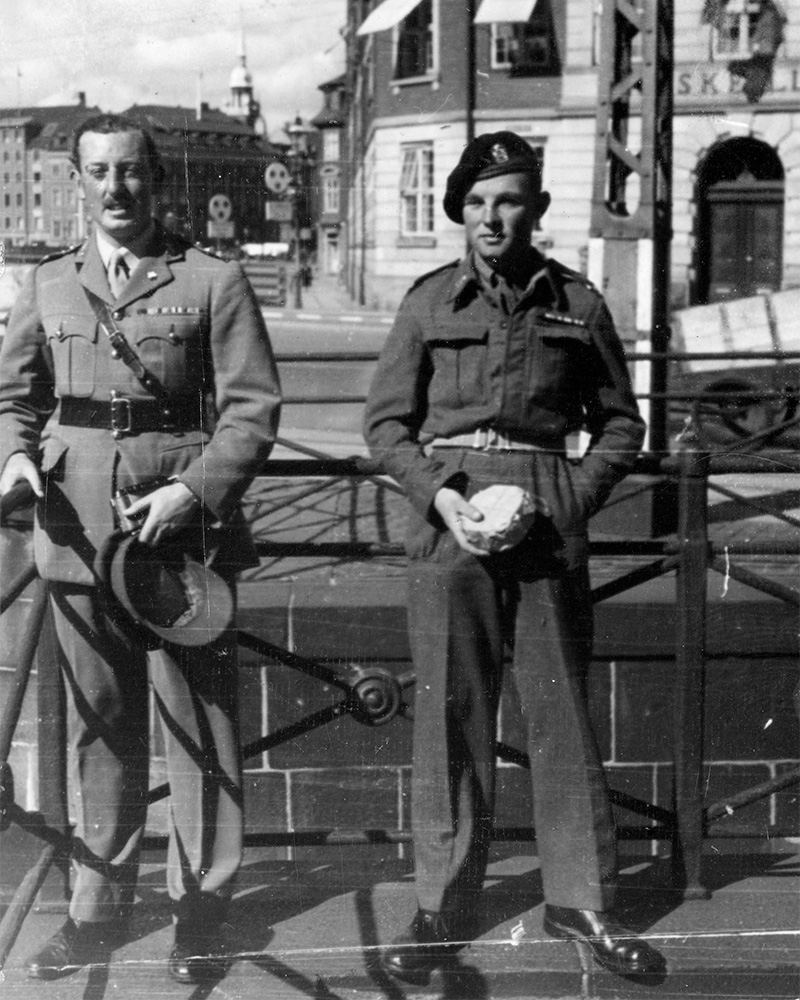

British troops in Copenhagen

Pat Dyas and Clifford Pace of the 3rd/4th County of London Yeomanry (Sharpshooters) are pictured here in Copenhagen.

After VE Day, the Danish capital became a popular sightseeing destination for British troops stationed in continental Europe.

‘Thorough examination has shown that the fairest and simplest scheme of release is one which is based on a combination of age and length of war service... The best balance as between age and length of war service is reached on the basis that two months of war service is equivalent to one additional year of age.’‘Release and Resettlement: an explanation of your position and rights’, booklet issued to all serving members of the armed forces

Demob

Twin sisters Amy and Frances Straw served in the Auxiliary Territorial Service as cooks. They joined on the same day and were both demobilised on 13 November 1945 after four years’ service.

Above, Frances (right) is shown helping Amy (left) to put on a civilian jacket.

Riots in Palestine

On 13 November, Britain's foreign secretary, Ernest Bevin, announced the creation of a joint commission of inquiry to examine the question of European Jews and Palestine. He clarified that existing limits on Jewish immigration would continue and all sides would be consulted prior to presenting a new plan to the United Nations.

After his announcement, Bevin told assembled journalists that Britain had agreed to establish ‘a Jewish home’ in Palestine and ‘not a state’.

In Tel Aviv, these proclamations inspired anger among Jews who saw it as a betrayal of the Balfour Declaration (1917). On 14-15 November, this anger turned into rioting: government buildings were torched, police and soldiers came under attack, and vehicles were overturned.

‘I am fully conscious of the great honour which has been done to me, in having been sent out as High Commissioner of this historic and beautiful country... Now, although the aftermath of the war has left a world wracked with misery and pain, the mind of man can be freed of the problems of destruction – freed to concentrate on the constructive phase now before us. The opportunity of making or marring the world lies before all of us.’Speech by General Sir Alan Cunningham upon becoming High Commissioner of Palestine — November 1945

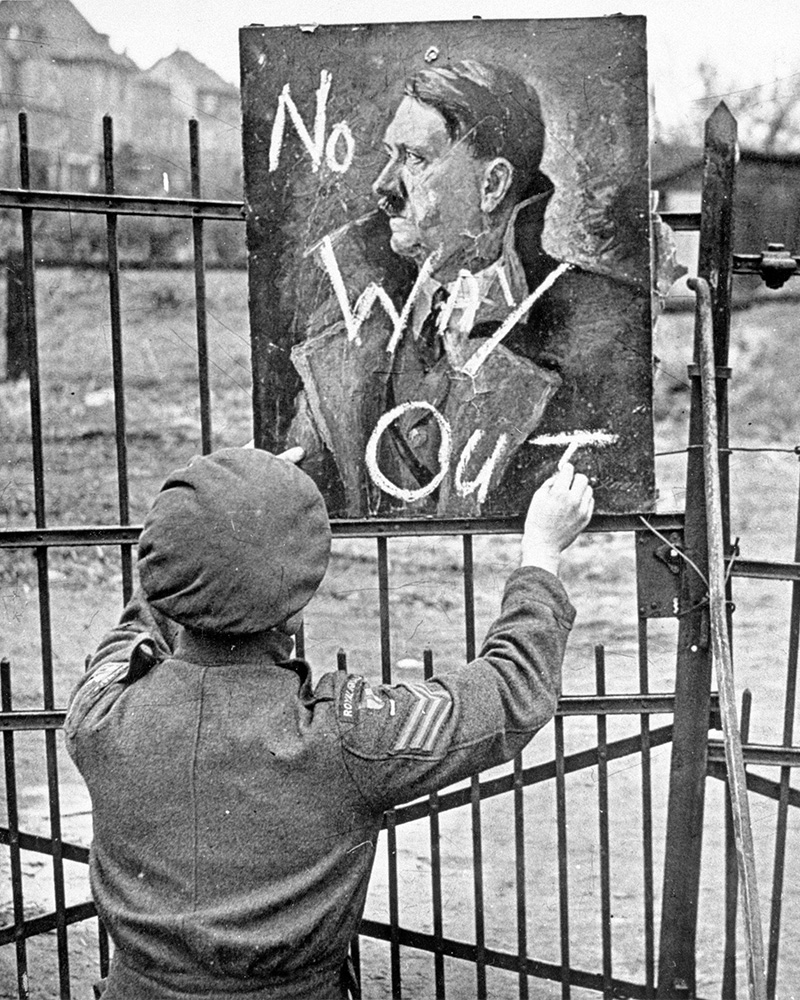

The Hitler Conspiracy

Throughout 1945, wild rumours continued to circulate that Adolf Hitler had survived the war and gone into hiding.

In November, after months of intensive investigation, British Army intelligence officers determined that Adolf Hitler and Eva Braun had indeed married on 29 April before committing suicide the following day in the Führerbunker, Berlin.

Despite substantial evidence to support this conclusion, some – including unrepentant Nazis – would continue to advance the conspiracy that Hitler was still alive.

Denazification and civilian internment

As the Allies continued their efforts to ‘denazify’ Germany, the number of internees grew significantly. By 15 November, more than 50,000 suspects had been arrested across the British Zone of occupation and detained in Civilian Internment Camps.

In most cases, there was no specific charge nor timeline for hearing a case. Inevitably, this began to cause tensions between the occupiers and the occupied.

Image courtesy of the IWM

Sentencing in the Belsen Trial

17 November 1945

After months of hearing evidence, the panel of British judges in the Belsen trial found 30 defendants guilty of at least one charge. Eleven were sentenced to death, including Josef Kramer, the camp's former commandant.

It was the first major trial of Nazis since VE Day and firmly demonstrated the Allies' initial enthusiasm for implementing their policy of denazification.

Entertaining the troops

During the war, the Entertainments National Service Association had offered troops a chance to relax and unwind, playing host to stars of stage and screen, such as Vera Lynn and George Formby. This continued after 1945 with the establishment of the Combined Services Entertainment Unit.

There were also more spontaneous efforts to organise sporting events, dances and musical performances – including an open invitation to professional football teams to tour the British Zone of Germany.

In late 1945, a Scotland XI toured the British Zone and played matches against service teams. With so many professional footballers still in uniform, these were often close contests.

‘To a growing murmur from the crowd on the opposite side of the field and a frenzy of action from the few cameramen by the entrance, the teams walked onto the pitch, two by two. The Combined Services in white shirts and dark shorts and the Scots in dark PT kit, sweaters and long pants... It was a far from clean encounter with the ‘ref’ having to warn two or three of the players, but, on the whole, quite good. The Scots were by far the better ball players but the Services somehow managed to make a 1–1 draw of it.’Letter from Lance Corporal John William Booth, serving in Germany with the 5th Royal Tank Regiment, to his parents — 19 November 1945

Officers’ Mess in Schloss Salzau

The mess was the centre of social life for most British soldiers in postwar Germany – a focal point for everything from inoculations and mailbags to drinks and dances.

Above, we see officers enjoying a beer together in the confines of Schloss Salzau, a historic castle in Schleswig-Holstein, Germany.

‘The show was a success, but second night audiences at all places were very small. We were asked to tour the Div area, but the eternal leave question cropped up, and with five of us away... it was quite impossible to play “Atmospheries”.’Letter from Gunner Ronald Clarkson, Royal Artillery, to his former commanding officer explaining the travails of an army concert band — 24 November 1945

International Military Trial at Nuremberg

20 November 1945 – 1 October 1946

On 20 November, the war crimes trial against the most senior surviving Nazi politicians and military officials began in Nuremberg, Germany.

Although located in the US Zone of occupation, this was an inter-Allied affair involving prosecutors from all four occupying powers, including Britain.

War correspondents make their way to Nuremberg

While war crimes trials were an attempt to bring those who had committed atrocities to justice, they were also a major media event.

During the 11 months of the Nuremberg trials, journalists like Maurice Watts (pictured) reported on the evidence, witness statements and the spectacle of leading Nazis appearing in the dock.

For the Allies, this was an attempt to show the world the depravity and criminality of the Nazi regime once and for all.

‘While we have the immediate administrative responsibility for feeding 25 million Germans, the threat of famine in our zone is one which we do not command enough food resources, shipping or foreign exchange to meet. The threatened catastrophe is in no sense strictly British but is definitely a United Nations’ concern because if it is not checked the political settlement of Europe and the withdrawal of occupying forces may be indefinitely postponed... and epidemics may be started whose spread it will be impossible to control.’Herbert Morrison’s report on ‘Food Supplies for Germany’ submitted to the Cabinet, London — 24 November 1945

The food crisis in Germany

Throughout 1945, there were severe food shortages across the whole of Europe. In occupied Germany, the problems were so stark that Army commanders warned of a potential famine that winter. The Allies were forced to confront a humanitarian disaster that could engulf the entire continent.

In the British Zone, hunger and deprivation were pervasive. The photograph above shows German civilians queuing for food in the town of Pinneberg. At some points, daily rations were cut to 1,550 calories per person per day, and even this amount of food was often hard to find.

To avert total catastrophe, the British government opted to fund the delivery of grain from North America to Germany.

‘A lot of folk out here are taking a very gloomy view of the winter from the German stand point, what a horrible mess the world seems to be in.’Captain Henry Hughes, Royal Artillery, in a letter to his wife, British Zone, Germany — 25 November 1945

Austrian elections

On 25 November, Austria - still under Allied occupation - held its first democratic election since 1930. Leopold Figl of the Austrian People’s Party won a decisive victory.

This marked a momentous step towards the renewal of Austrian sovereignty, even if inter-Allied disagreements would delay the end of the military occupation until 1955. Until then, a garrison of British troops remained in Vienna, as well as the regions of Carinthia, East Tyrol and Styria.

Control Commission for Germany

Across the British Zone, members of the Control Commission for Germany (CCG) continued to work to enact the Potsdam Agreement.

This battle dress blouse, with CCG markings, was worn by Major GR Wemyss-Swann, formerly of the Royal Indian Army Service Corps.

‘The plan envisaged at Potsdam for the orderly and humane transfer of German populations, has now been completed and approved by the Allied Control Council. The rate of transfer is to be gradual and such as to minimise hardship.’John Hynd, minister in charge of the British Zone, Germany, House of Commons, London — 26 November 1945

The Refugee Crisis

In 1945, the Allies agreed to a population transfer of several million people westwards from eastern Europe. Amid terrible weather conditions, brutal treatment and insufficient supplies of food or shelter, the official request for an ‘orderly and humane’ transfer turned out to be a fallacy. The ensuing refugee crisis was on an unprecedented scale.

On the hunt for secrets

By the end of 1945, T-Force - the secretive British Army unit set up to retrieve German industrial and scientific secrets - had achieved many of its primary goals. Yet the work of transporting material back to Britain was still ongoing.

In addition, British troops were involved in ‘denial’ efforts intended to keep potentially valuable secrets from the Soviet Union.

‘The “target” side of our T Force role had diminished almost to vanishing point, but there was still much work to be done in the collection, packing and dispatch of equipment, much of it needed as reparations. T Force now provided the normal channel through which all industrial plant was evacuated from Germany and was playing its part in helping to re-equip British and Allied factories at the expense of the enemy. Some 3,000 investigators of diverse nationalities had passed through its messes, some 350 items of equipment weighing nearly a thousand tons had been evacuated, and 156 German technicians, out of 180 schedules, had been traced and exploited.’Captain JD Bicknell’s ‘War Chronicle of the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry 1944-1945’, British Zone, Germany — November 1945

Image courtesy of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

Hess confesses at Nuremberg

On 30 November, Nazi leader Rudolf Hess informed the tribunal at Nuremberg that his claims of amnesia had been a pretence. He was now prepared to stand trial and ‘bear full responsibility for everything I have done’.

The prosecution case against him would begin in February 1946. In the photograph above, Hess is seated in the front row of the dock, second from the left, between Hermann Göring and Joachim von Ribbentrop.

On 1 October 1946, Hess was found guilty of conspiracy and crimes against peace. He was given a life sentence.

Fighting between British troops and Zionist terrorist groups continues

On 25 November, armed Zionist terror groups blew up two coastguard stations and a number of British police stations near Tel Aviv. This was retaliation for the seizure of a ship carrying Jewish immigrants as Britain continued to restrict migration to Palestine.

In response, 10,000 British troops swept through the Sharon plain and forced their way into the kibbutzim of Shefayim and Givat Haim searching for those responsible. This led to violent clashes with Jewish civilians.

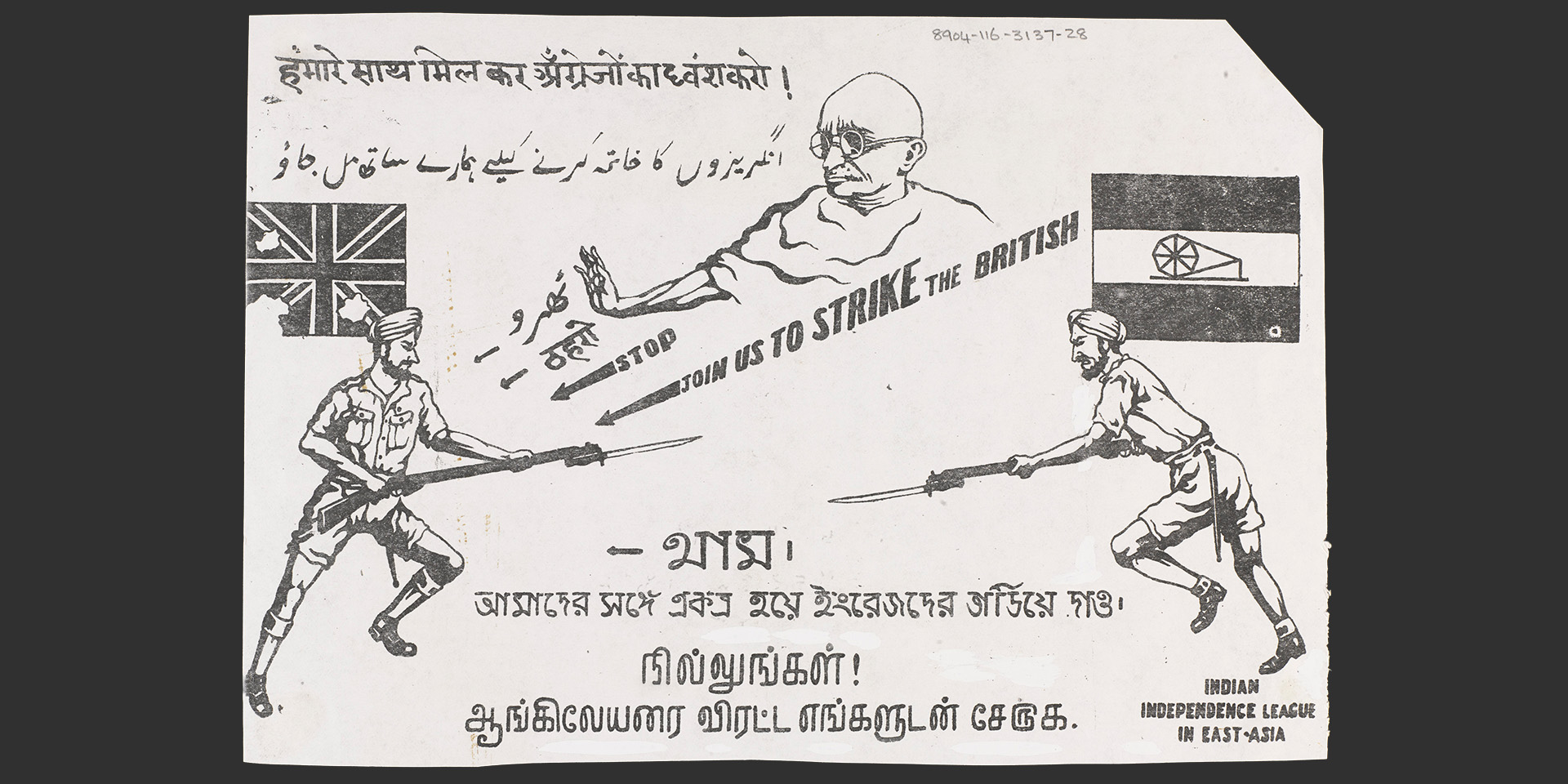

‘Stop! Join us to strike the British!’

This propaganda leaflet features an Indian soldier under the British flag (on the left) confronting a member of the Indian National Army (INA) beneath the flag of the pro-independence Indian National Congress party (on the right). A depiction of independence leader Mahatma Gandhi looms above them.

Written in Hindi, English, Urdu, Tamil and Bengali, the slogan reads ‘Stop! Join us to strike the British!’

The INA had fought on the side of Japan during the war. Despite its relative military insignificance, this force held substantial political weight in the aftermath of the conflict. With support from the Indian National Congress, soldiers of the INA were now widely heralded as freedom fighters.

Indian National Army trials incite anger against British

In November 1945, the trials of INA soldiers Shah Nawaz Khan, Gurubaksh Singh Dhillon and Prem Sahgal began at the Red Fort in Delhi. The prosecution inspired widespread protest among Indian civilians.

In Calcutta (now Kolkata) and Bombay (now Mumbai), popular anger broke into rioting. On 23 November, British police killed 37 rioters in Calcutta.

All three defendants were found guilty of 'waging war against the King' and sentenced to transportation for life. Amid huge public pressure - and fearing further unrest - Claude Auchinleck, Commander-in-Chief of the Indian Army, commuted their sentences.

On This Day: 1945

This is the penultimate instalment of a series exploring the British Army's role in 1945 – one of the most decisive years in modern history – drawing upon the National Army Museum's vast collection of objects, photographs and personal testimonies.

Throughout 2025, a new instalment will be released each month that focuses on events from 80 years beforehand. The series will highlight the everyday experiences of Britain’s soldiers alongside events of grand historical significance.