Boy soldier

Matthew Tuck was born in St John’s Wood, London, in December 1861. Little is known of his early life, but surviving records reveal that he grew up in poverty, spending time in a residential workhouse school in Lambeth.

This disadvantaged background may account for his decision to become a soldier. During this period, conditions in the Army were so notorious that many recruits only joined up out of desperation.

Tuck enlisted at Portsmouth on 28 November 1874, joining the 58th (Rutlandshire) Regiment of Foot, which had recently returned from India. At the time, Tuck would have been just 13 years old. Like many other boy soldiers, he became a member of the regimental band.

Fanfare farewell

In February 1879, Tuck’s regiment embarked on foreign service. This new adventure inspired him to keep a diary.

To the noise of cheering crowds and performing bands, the men of the 58th Foot departed from Portsmouth on the troopship ‘Russia’. They were bound for the British colony of Natal (now part of South Africa's KwaZulu-Natal province), where Britain had recently initiated a war with the neighbouring Zulu Kingdom.

The voyage was almost certainly Tuck’s first taste of foreign travel. However, his diary reveals that his sense of wonder was tempered by impatience. By the time he arrived at the port of Durban on 4 April, he was eager for action.

Zulu War

The Zulu Kingdom shared borders with the Boer republic of Transvaal (to the north-west) and the British colony of Natal (to the south-west). The British were keen to build a federation of territories across the region. To this end, they had invaded Zululand in January 1879.

Although equipped mainly with spears and shields, the Zulus proved formidable opponents. On 22 January, they inflicted a stinging defeat upon a British column at Isandlwana.

Anxious to avenge this perceived humiliation - and to bring the war to a successful conclusion before he could be replaced - the British commander, Lord Chelmsford, prepared his forces for another invasion in the summer.

Scares and skirmishes

Tuck and his regiment played their full part during this campaign, joining the invasion force on the border of Zululand after an arduous march of over 200 miles (320km).

This army of around 6,000 men advanced into Zulu territory at the end of May 1879. Although they encountered no serious resistance, they were ever mindful of the threat posed by their enemy, and still had to endure some nasty scares and skirmishes.

From tragedy to farce

The most famous of these encounters came on 1 June, when Louis-Napoleon – the only child of the exiled French emperor Napoleon III - was caught in a Zulu ambush and killed. The Prince Imperial had only been allowed to accompany the British forces in Africa following the personal intercession of Queen Victoria.

In his diary, Tuck remarked on the ‘great regret and excitement’ that this event stirred within the column.

A few days later, Tuck’s own regiment narrowly avoided a further tragedy. When a false alarm was sounded at night, a small party of soldiers on guard duty were fired upon by their own comrades and were lucky not to have been killed.

Tuck was able to see the funny side of the panic that had broken out in the camp. His diary paints a comic picture of the men as they struggled to rouse themselves for action in the dark

‘The alarm shots are heard from the outpost, every man in the tent and it is in pitch darkness, then comes the scramble for rifles, belts and other things... Outside some of the fortunate ones having arms and belts are shouting “down with the tents”, the men inside shouting “stop a minute” where’s my rifle, everyone around cursing and swearing, when at last you manage to get hold of a rifle and now you wonder what keeps the gun as firm, little thinking in the darkness that another man has hold of the same gun as yourself, “what is the matter with the gun you keep saying” ditto the other man, until you make a desperate effort pulling it clean out of his hand. Down you go backwards across the tent with your heels in the air knocking down two or three in your journey, “who is that”? is shouted from all sides and if you get off with a couple of kicks you may think yourself lucky. You no sooner pick yourself up then down comes the tent on top of you (for all the tents are struck to leave the ground clear). Leaving you to struggle out the best way you can. After you do get out you see some of the most comical sights you could imagine. Some without boots, some without helmets, others struggling to get into their belts upside down, others trying to get into a blanket instead of a great coat, and wondering where the sleeves had got to.’Matthew Tuck describing the muddle that ensued when a night alarm was sounded during their advance into Zululand in June 1879

A brutal conquest

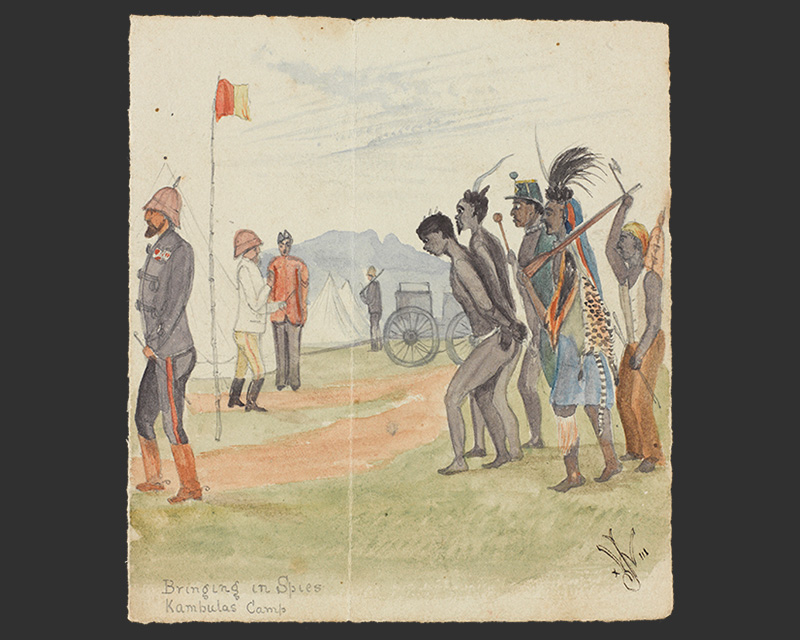

However, such humour belied the harsh nature of the conflict and the ruthlessness with which it was waged by the British. These aspects are revealed in other diary entries.

Tuck noted how captured Zulus were executed or sent for punishment as spies. He also recorded how the British laid waste to the land, destroying settlements (kraals) and burning crops in a concerted effort to destroy the Zulus’ capacity to resist.

The prejudice of the British towards the Zulus is also laid bare, with Tuck referring to them as ‘black savages’. Abhorrent today, such language was commonplace in the Victorian period. It often stemmed from a feeling of racial superiority that many British people felt at a time when their colonial empire was rapidly expanding.

Ulundi

On 4 July, the British forces reached the Zulu capital, Ulundi. Here, the decisive battle of the war was fought.

Lord Chelmsford drew up his army into a defensive square and used superior firepower to defeat a force of 20,000 Zulus, who attempted to overwhelm the British with repeated charges of great courage. Around 6,000 Zulus were killed, while British casualties in both dead and wounded were fewer than 100.

Tuck drew satisfaction from this emphatic victory, noting the praise his regiment received from the British commanders, Chelmsford and Newdigate, for its steadiness in action.

The victory was completed by the burning of Ulundi and by the capture of the Zulu king, Cetshwayo, the following month.

‘A hot engagement ensued for one hour and a half inflicting severe loss on the enemy’s side but few on the British. The whole of the Zulus fled and we advanced in square four deep towards the great city and we burned it to the ground and left nothing standing. Our men picking up what curiosities they could and we witnessed hundreds of dead Zulu bodies lying about.’Matthew Tuck recounting the Battle of Ulundi fought on 4 July 1879

Life on campaign

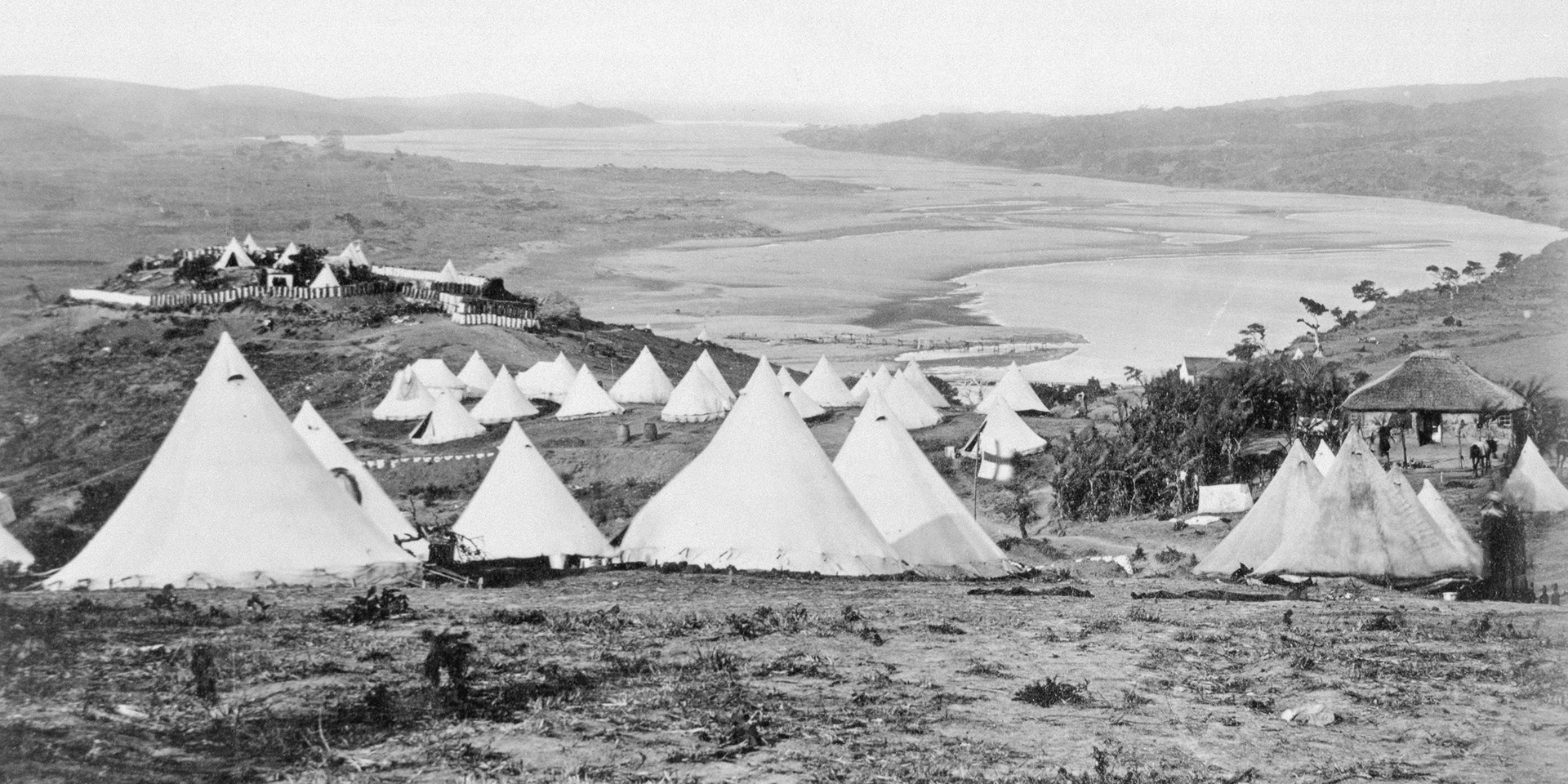

The 58th Foot remained in Africa after the victory at Ulundi and continued to march about the country, living under canvas. Tuck’s diary from this time provides many insights into ordinary life on campaign, including details on the weather, landscape, food, morale and recreation.

Particularly revealing is a description of a 45-mile (72km) march from Dundee in Natal to Utrecht in Transvaal undertaken in October 1879. This story is laced with humour, as Tuck recounts the amusing appearance of the men in their increasingly dilapidated uniforms, placing a comic slant on the many hardships, privations and injustices they endured.

‘On we trudge like the Duke of York with his thousand men up one hill and down another one again, only to see another appear. No regular road, only a beaten track. No vegetation, nothing but – yes there was, I had nearly forgotten, you must have heard the charge of the Light Brigade, but instead of guns it was (in S Africa) ant hills in front of us, ant hills in rear of us, ant hills to the right of us, ant hills to the left of us, in fact it was nothing but ant hills when not employed against the enemy.’Matthew Tuck describing the South African terrain during a march in October 1879

A Boer holding a Martini-Henry rifle, 1880

A new era of warfare

Early in 1881, Tuck and his comrades in the 58th Foot were called into action for a new conflict which had broken out in Transvaal. This time, they would be fighting the Boers, fiercely independent descendants of Dutch settlers who were just as intent on resisting British expansion as the Zulus.

In stark contrast to the massed attacks of the Zulus, the Boers fought in a loose skirmish formation and made use of terrain to conceal their positions. Most significantly, they were skilled in the use of breech-loading rifles, which enabled them to engage the British effectively at long range.

In these ways, the Boers heralded a new era in the history of warfare.

Laing’s Nek

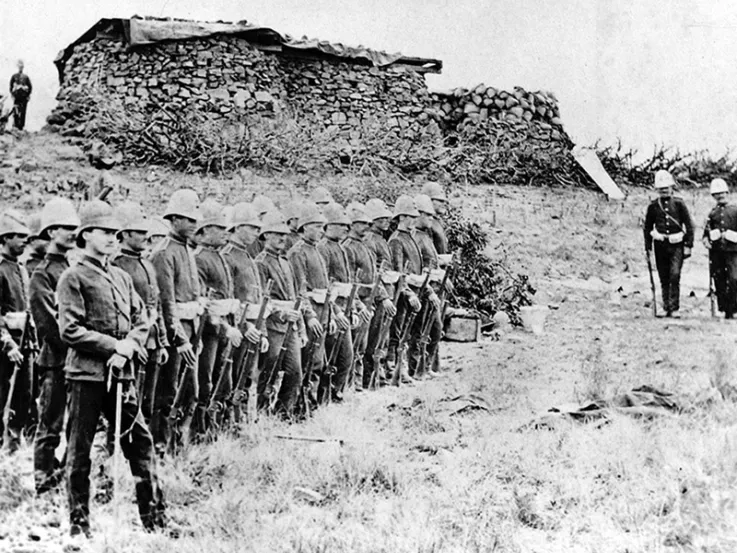

On 28 January, the 58th Foot went into action against the Boers at Laing’s Nek, a strategically important pass over the Drakensburg Mountains.

As the spearhead of a force of 1,500 men under Major General Sir George Pomeroy-Colley, Tuck and his comrades advanced laboriously uphill to engage the enemy. Already exhausted by the time they reached the summit, they were unable to charge the Boers who were widely dispersed and well-concealed behind boulders.

As the British attack faltered, the Boers opened a devastating volley of rifle fire upon them, inflicting heavy casualties and driving the regiment into full retreat.

'The Boers' method of fighting', The Illustrated London News, No 2177, Volume 78, 5 February 1881

Wounded in action

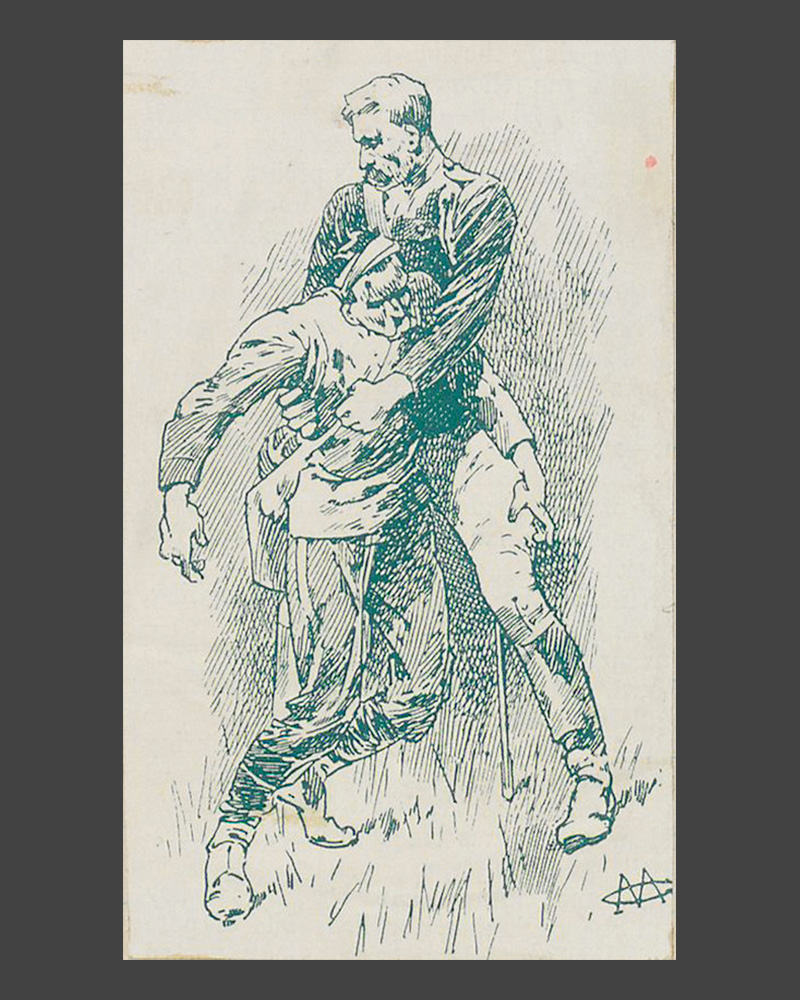

Tuck was among the casualties, receiving a nasty wound to his left ankle. He was lucky to be carried away by Lieutenant Alan Hill (later Hill-Walker), one of three rescues for which Hill was to be awarded the Victoria Cross. Many others were not so fortunate - 150 men had been killed in the assault and many more were seriously wounded.

'Lieutenant Hill assisting a wounded comrade', contemporary newspaper illustration, c1881

Peace

Negotiations soon brought the war to an end, but not before the Boers had inflicted further defeats upon the British. One of these, at Majuba Hill, saw the death of Major General Pomeroy-Colley.

The peace proved precarious. Further conflict with the Boers, on a far greater scale, was to erupt once more at the close of the century.

Convalescence

Tuck was taken to the British camp of Mount Prospect, where he received initial treatment and took in news of the war.

Despite the severity of his wound, it would be six weeks before he was moved 20 miles (32km) to a hospital at Newcastle in Natal - a painful and difficult journey in jolting wagons.

After an operation to remove fragments of bone and metal from the wound, Tuck’s condition remained serious. The shattered ankle was compounded by fever and a skin infection known as erysipelas. He was lucky not to require amputation.

‘I have had narrow escapes of losing my foot, and up to the present day I have wondered how I escaped the unhappy decision, but I was told that owing to my youth I would stand a chance of regaining strength, although I would be a case of long standing, which afterwards proved as such.’Matthew Tuck recounting how he narrowly avoided having his foot amputated in 1881

Leaving the Army

The extent of this injury put an end to Tuck’s military career. After returning to England in October 1881 and undertaking a further period of convalescence at Netley Hospital near Southampton, he eventually regained some use of his foot. However, he was passed unfit for service by a medical board and formally discharged from the Army on 11 April 1882.

Soldiers relaxing by Southampton Water with Netley Hospital in the background, c1902 (Image courtesy of the Wellcome Collection)

Later life

On leaving the Army, Tuck received a pension of one shilling and three pence. This was later renewed at one shilling per day – a paltry sum equivalent to around £5 today.

He returned to London, where he joined the Corps of Commissioners in June 1882. This organisation had been founded in 1859 by Captain Sir Edward Walter to provide employment for veterans.

Tuck later found work as an estate agent. After getting married and raising a family, he retired to the Isle of Wight, where he died in July 1942, at the age of 80.

You can read a digitised version of his diary online. Please be aware that this material contains racist language.

Access to the Archive

The National Army Museum provides public access to its library and archival collections via the Templer Study Centre. Over the coming weeks and months, we will be sharing more stories across our website and social media channels, highlighting some of the valuable personal insights these collections hold.