Facts and figures

Until 1940, the Victoria Cross (VC) was Britain's highest award for gallantry. Since then, it has been equal in status to the George Cross (GC), which was instituted for acts of conspicuous bravery not performed in the enemy's presence.

There is no barrier of colour, creed, sex or rank. Indeed, VC recipients have come from all social backgrounds and from all over the British Empire and Commonwealth.

In all, 1,358 VCs have been issued since the award's inception in 1856. Of these, 626 were issued for service during the First World War (1914-18), and 181 for service in the Second World War (1939-45). The total figure includes extra bars added to the VCs of three soldiers who had already won the award before, and the VC awarded to the Unknown Soldier buried at Arlington National Ceremony in the United States.

Lance Corporal Joshua Leakey, of 1st Battalion The Parachute Regiment, is the most recent recipient of the VC. His award was publicly announced in February 2015, following an action in Afghanistan on 22 August 2013.

Foundation

The VC was instituted by Royal Warrant on 29 January 1856 to acknowledge the bravery displayed by many soldiers and sailors during the Crimean War (1854-56). Unlike its predecessors, the new award was open to all ranks and would only be presented for acts of supreme gallantry in the face of the enemy.

The first 85 awards - announced in 'The London Gazette' of 24 February 1857 - were made retrospectively, dating back to the start of the Crimean campaign in the autumn of 1854.

Quiz

Who won the first VC?

On 21 June 1854, Lucas was serving on HMS 'Hecla', bombarding Bomarsund, a fort in the Aland Islands, off Finland. A live shell from a shore battery landed on the ship's upper deck, with its fuse still hissing. All hands were ordered to fling themselves flat, but Lucas with great presence of mind ran forward and hurled the shell into the sea, where it exploded. Thanks to his action, nobody was killed or wounded. Lucas was immediately promoted to lieutenant by the ship's captain.

Design

The prototype Victoria Cross was made by the London jewellers Hancocks & Co, who still make VCs for presentation today.

According to legend, the prototype, along with the first 111 crosses awarded, were cast from the bronze of guns captured from the Russians in the Crimea. There is, however, a possibility that the bronze cannon used was in fact Chinese, having been captured during the First China War (1839-42) and then stored at the Royal Arsenal, Woolwich.

The decoration takes the form of a cross pattée, 1.375 inches (35mm) wide, bearing a crown surmounted by a lion, with the inscription ‘For Valour’. This was originally to have been ‘For Bravery’, but it was changed on the recommendation of Queen Victoria, who worried that some might mistakenly assume that only recipients of the VC were deemed to have been brave in battle.

Originally, the VC ribbon was dark blue for the Royal Navy and crimson for the Army. Shortly before the Royal Air Force was formed in 1918, King George V approved the recommendation that the crimson ribbon should be adopted by all three services. When the ribbon is worn alone, a miniature of the cross is pinned on it.

First investiture

The first 62 crosses were presented to veterans of the Crimean War by Queen Victoria in June 1857. The event, which took place in London's Hyde Park, was attended by large crowds who greeted the VC heroes with rapturous applause.

The Queen elected to stay on horseback throughout the ceremony, and apparently stabbed one of the recipients, Commander Henry Raby RN, through the chest as she pinned the cross to his uniform. Commander Raby is said to have stood unflinching as the pin was fastened through his flesh!

Quiz

What is the record for the most VCs awarded on the same day?

Eighteen VCs were awarded for actions that took place on 16 November 1857. Seventeen of these were during the Second Relief of Lucknow (Indian Rebellion); the other was at Narnaul, near Delhi. (Further VCs were awarded for gallantry at Lucknow over a broader time period, but not specifically for action on 16 November.)

Recommendation

The VCs awarded to Crimean veterans were recommended retrospectively. There was much lobbying by individuals and regiments to receive the new decoration. Most of this was unsuccessful.

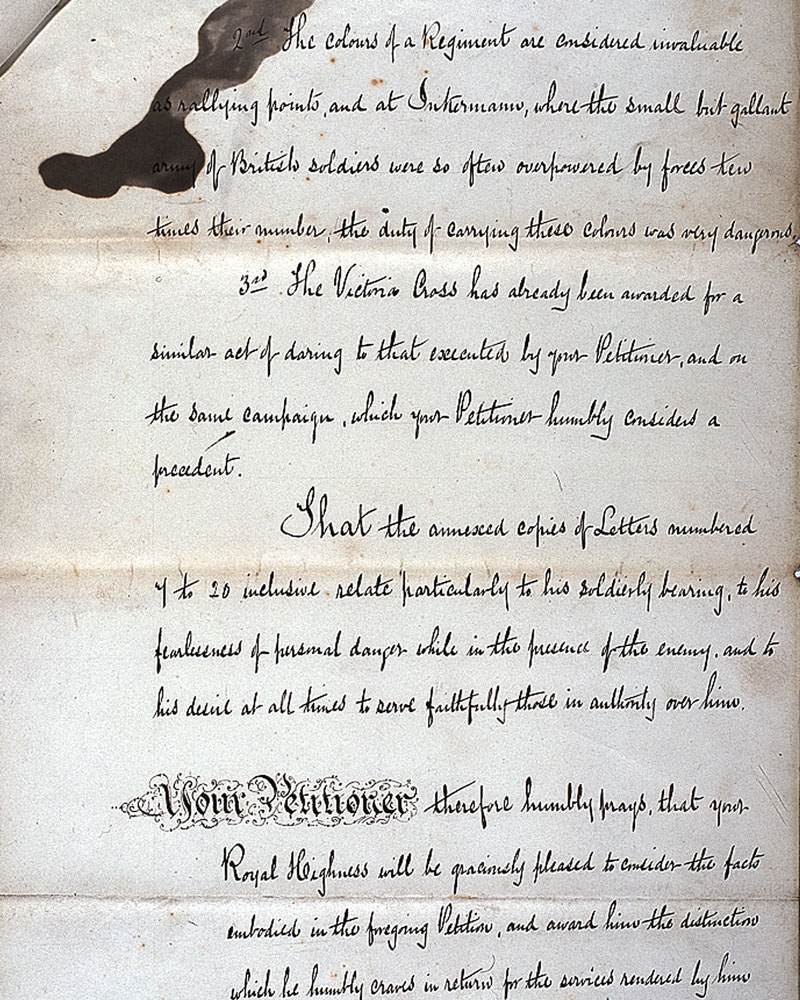

The document displayed below was written by Lieutenant John Brophey, who received the Distinguished Conduct Medal for his actions as a colour-sergeant at the Battle of Inkerman (1854). He later petitioned the Commander-in-Chief, the Duke of Cambridge, for the retrospective award of the VC, but his hopes were thwarted.

A recommendation for the VC was normally issued by an officer at regiment or ship level, and had to be supported by three witnesses. From there, it was passed up the military hierarchy until it reached first the Secretary of State for War, and then the monarch.

Rule 13

The original Royal Warrant stated that the VC could also be awarded by ballot, if a large body of men - such as a battalion or ship’s crew - performed an act of gallantry collectively. Normally, the officers involved selected one of their number to receive the award. Likewise, one petty officer or non-commissioned officer and two seamen or private soldiers were selected by their peers.

On 31 March 1900, British troops were ambushed on their march to Bloemfontein by Boer commandos. Under heavy fire, 'Q' Battery, Royal Horse Artillery, managed to rescue all but one of their guns. Every man in the battery showed considerable bravery.

Under Rule 13 of the Royal Warrant, four officers and men were nominated by their fellows for the award. Gunner Isaac Lodge was elected, together with his commanding officer, Major Edmund Phipps-Hornby, Sergeant Charles Parker and Driver Horace Glasock.

Changes to Warrant

Since the inception of the VC, there have been 14 further Royal Warrants that have changed the original terms and conditions set out for awards. Recognising the bravery of civilian volunteers during the Indian Mutiny (1857-59), an 1858 warrant extended the eligibility of the VC to ‘non-military persons’ serving with the forces.

Seven civilians have been awarded the VC: Thomas Kavanagh (1857); William Fraser McDonell (1857); Ross Lowis Mangles of the Bengal Civil Service (1857); George Bell Chicken, a civilian volunteer with the Indian Naval Brigade (1858); the Reverend James Adams of the Bengal Ecclesiastical Department (1879) and Captains Frederick Parslow and Archibald Smith of the Mercantile Marine (1915-17). The latter two recipients were posthumously commissioned into the Royal Naval Reserve to make them eligible for the VC.

In 1867, in recognition of the services performed by local auxiliary units during the Maori uprisings in New Zealand (1863-66), eligibility for the VC was extended to local forces serving with Imperial troops. This eligibility was further extended to all colonial and auxiliary troops in 1881.

Posthumous awards

When the VC was first instituted, the original Royal Warrant made no mention of posthumous awards. It had been decided from the outset that the VC would not be awarded for an act in which the potential recipient was killed, or where he died shortly after.

Instead, in these circumstances, an announcement was made in 'The London Gazette' that the person would have been recommended for the VC had they survived.

There were six instances of this between 1859 and 1897, including Lieutenants Nevill Coghill and Teignmouth Melvill, who were killed attempting to save their unit's Queen's Colour after the defeat at Isandlwana on 22 January 1879.

Further change

In 1900, during the Boer War (1899-1902), a posthumous VC was awarded to Lieutenant Frederick Roberts of the King’s Royal Rifle Corps. The son of Field Marshal Lord Roberts, Frederick was mortally wounded attempting to save the guns of the 14th and 66th Batteries, Royal Field Artillery, at Colenso on 15 December 1899. He died 24 hours after being recommended for the VC.

This was the first award that included the wording ‘since deceased’ after the recipient's name. It established the precedent by which a VC recommendation could still be processed if the soldier subsequently died prior to publication in 'The London Gazette'.

During the remainder of the Boer War, several more posthumous VCs were granted. In 1907, it was announced that the six posthumous cases from between 1859 and 1897 would also be retrospectively awarded.

Despite the fact that posthumous VCs continued to be granted during the First World War (1914-18), it was not until 1920 that specific provision for posthumous awards was finally made by Royal Warrant.

Indian troops

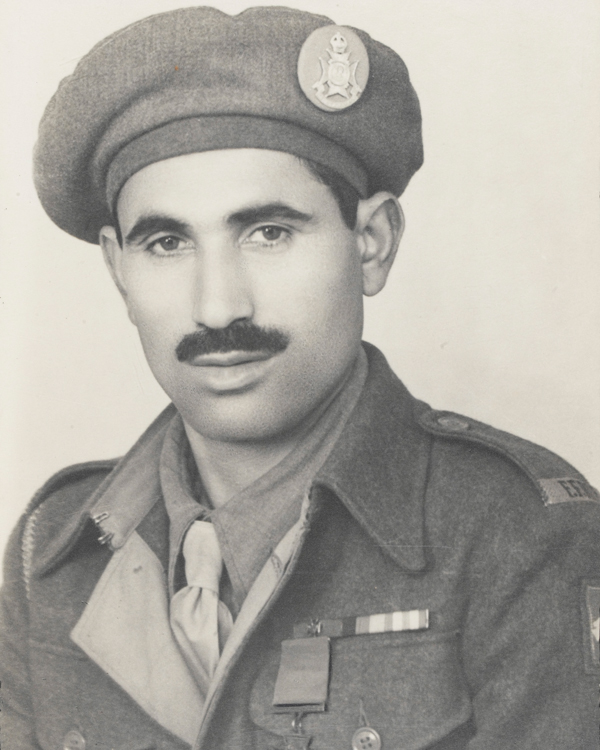

The Royal Warrant of 21 October 1911 - published in 'The London Gazette' of 12 December 1911 - extended eligibility to Indian soldiers. Prior to this, the award of the VC was restricted to Europeans in the Indian Army (and its East India Company predecessors). Since then, 29 soldiers from the Indian subcontinent have been awarded the VC.

The first Indian recipient was Sepoy Khudadad Khan of the 129th Duke of Connaught's Own Baluchis. On 31 October 1914, at Hollebecke in Belgium, he continued to man his machine gun, despite being wounded, until the other men of his detachment had been killed.

Forfeiture

Under the terms of the original Royal Warrant, there was a clause that allowed for a recipient's name to be erased from the official list of holders in certain circumstances. Between 1856 and 1908, eight cases of forfeiture took place, for a variety of criminal offences including theft and bigamy.

Private Frederick Corbett forfeited his VC after being found guilty at a court martial of absence without leave, embezzlement, and theft from an officer. Private George Ravenhill's VC was forfeited after he was imprisoned for theft, having proved unable to pay a ten shilling fine.

However, King George V felt strongly that the decoration should never be forfeited. In a letter written by his Private Secretary, Lord Stamfordham, on 26 July 1920, it was stated: ‘The King feels so strongly that, no matter the crime committed by anyone on whom the VC has been conferred, the decoration should not be forfeited. Even were a VC to be sentenced to be hanged for murder, he should be allowed to wear his VC on the scaffold.’

The various VC warrants also gave the sovereign the power to cancel any forfeiture and restore both the award and pension. The eight instances of forfeiture, therefore, continue to be included on the official War Office list of VC holders.

Multiple awards

The Royal Warrant also made provision for soldiers to receive additional VCs, should they perform subsequent acts of outstanding gallantry. Three men have won the VC twice, receiving an extra bar to their original cross.

Major Arthur Martin-Leake won his VC while serving as a surgeon with the South African Constabulary during the Boer War on 8 February 1902 at Vlakfontein. He received a bar to his cross for bravery during the period 29 October - 8 November 1914 near Zonnebeke on the Western Front.

Captain Noel Chavasse of the Royal Army Medical Corps was awarded the VC on 9 August 1916 at Guillemont on the Somme, and a posthumous bar for gallantry between 31 July and 2 August 1917 at Wieltje in Flanders.

Finally, Captain Charles Upham, 20th Canterbury and Otago Battalion, New Zealand Expeditionary Force, won the VC for his actions on the island of Crete during 22-30 May 1941, and a bar for bravery in Egypt on 14-15 July 1942.

Quiz

Who was the youngest VC winner?

The youngest winner of the VC was 15 years and three months old. Hospital Apprentice Andrew Fitzgibbon, Indian Medical Establishment, won the VC on 21 August 1860 at the storming of the North Taku fort during the Second China War (1857-62). Throughout the fighting, he repeatedly attended to wounded men while under fire.