Alcohol

During the 18th and early 19th centuries, the public consumption of alcohol was commonplace across British society. This was partly due to its accessibility in a time before more stringent licensing laws, but also because drinking water was often dirty. Many people drank a weak type of ale known as 'small beer' as an alternative, but others turned to stronger alcoholic drinks like gin.

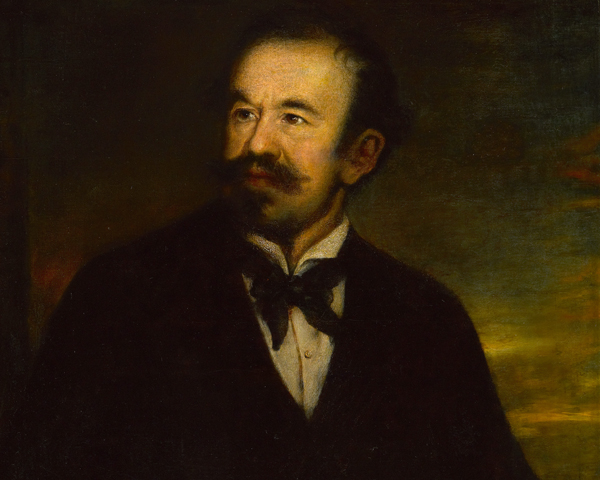

However, there was an increasing awareness of the negative effects of alcohol on society, with many commentators - such as the artists William Hogarth and George Cruickshank, whose father died of alcoholism - noting its pernicious effects.

By the 1830s, temperance societies were increasing in number. Most used moral persuasion to convince people to stop drinking, but a few campaigned for an outright ban on alcohol sales. The temperance campaigners organised mass meetings, published newspapers and opened temperance bars and hotels.

Many of the societies had religious connections or were associated with the growing number of social reform and philanthropic movements concerning themselves with the plight and habits of the working classes.

Army drinking

The Army was not immune to these currents of opinion. Heavy drinking, and the disciplinary issues and insubordination resulting from it, had long been a problem. Despite harsh punishments for drunkenness, such as flogging and demotion, soldiers still consumed huge amounts of alcohol.

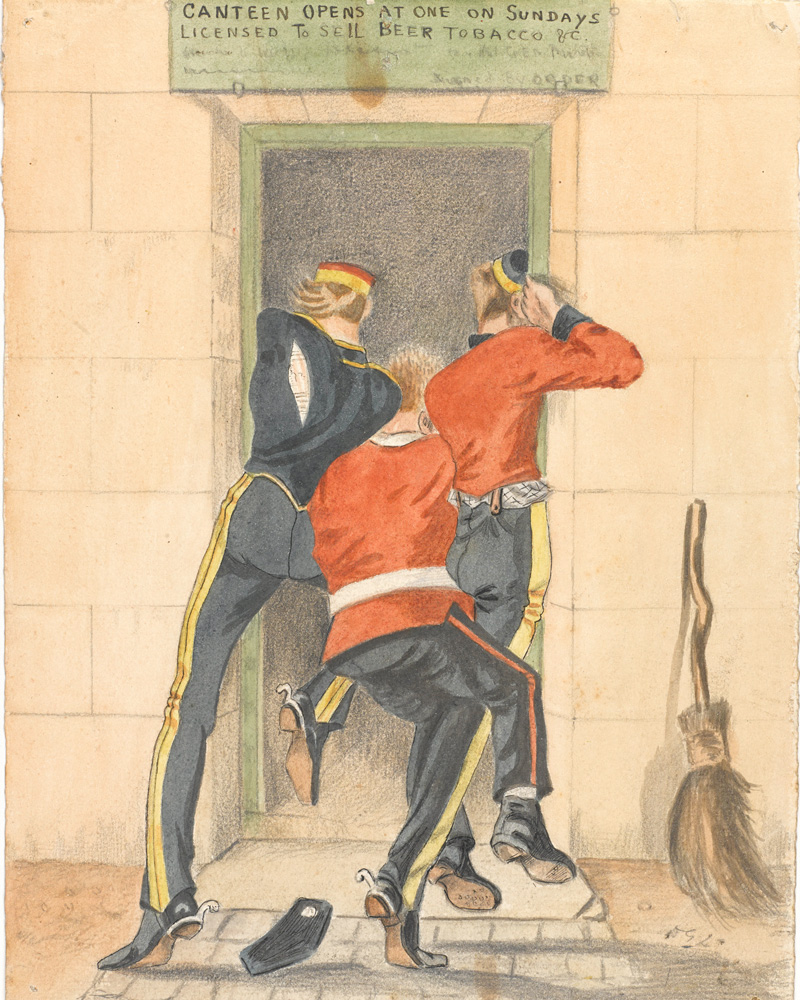

It was partly the lack of meaningful activities or recreation that drove many troops to the tavern and canteen. Barrack life was often monotonous, especially for soldiers stationed overseas, and the situation wasn’t helped by their unappetising rations. The Victorian soldier Edwin Mole noted that ‘at least half a dozen men, after a look at the dish, lit their pipes and went off to the canteen’.

'The facility to drinking at Gibraltar was a great cause of punishment and led to every other excess.’Major General Sir Joseph McLean — 1836

Overseas

On many foreign stations, the consumption of alcohol was officially encouraged. Soldiers serving in the West Indies, where service was seen as a virtual death sentence, were issued a rum ration that was believed to be a prophylactic medicine for yellow fever, as well as other life-threatening diseases.

This, however, led to an inordinate amount of locally produced ‘New Rum’ being consumed, which caused both alcohol and lead poisoning, the latter from the condensing coil tubes used in the distilling process.

Similarly, troops in India received a daily issue of spirits to help them withstand the rigours of the climate. They also had easy access to ‘country spirits’, usually arrack, and this combination was blamed for numerous ‘hot-weather shootings’, whereby a drunken soldier would grab his rifle and shoot a comrade.

A curb on drinking

With much of the Army's crime and indiscipline stemming from alcohol abuse, regiments in India and at home in Britain tried hard to reduce the perils of the bar and canteen. Commanding officers encouraged sports like cricket, and developed games rooms, reading rooms, flower and vegetable gardens as diversions.

Some officers also provided teetotal soldiers with alternative drinks and encouraged their men to hold tea parties, complete with cake. Other officers advocated religious instruction as a way of keeping soldiers away from the tavern. From the 1840s onwards, regimental and garrison temperance associations were also established to encourage and reward alcohol abstinence.

Havelock’s club

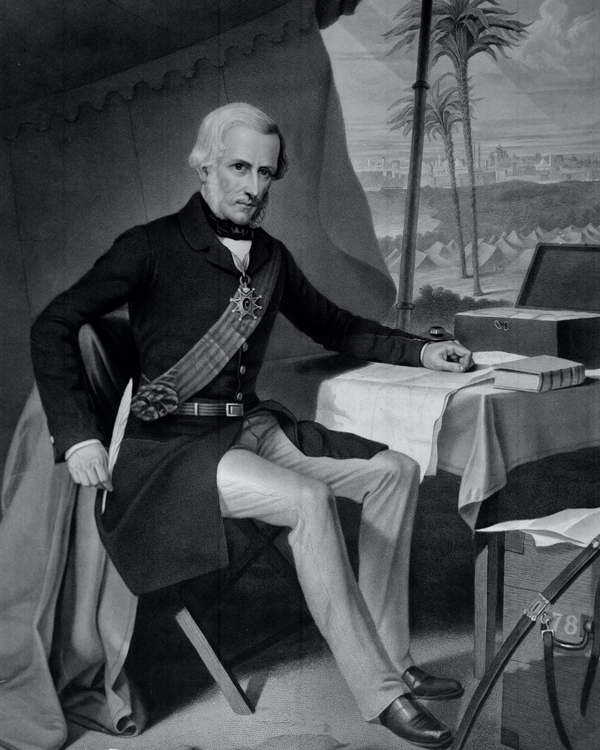

One of the earliest Army temperance societies was established in Burma by Lieutenant (later General Sir) Henry Havelock of the 13th Regiment in 1823. Its members were dubbed 'Havelock's Saints'. Indeed, his wife's family were missionaries and this religious zeal no doubt inspired him to begin bible classes for his soldiers. On becoming adjutant of the 13th in India in 1839, he formed the first regimental temperance society.

Havelock later died of disease during the Indian Mutiny (1857-59), but was commemorated by the Army Temperance Society with the 'Havelock Cross', awarded for seven years’ temperance. Many regimental temperance societies were subsequently formed in India, numbering over 50 by 1850.

Indian abstinence

The success of regimental societies in India, along with the increasing number of British personnel stationed there following the Mutiny, led to more ambitious plans for larger temperance organisations in garrisons across the subcontinent. These included the Outram Institute, founded by General Sir James Outram, and the Soldiers’ Total Abstinence Association, formed by Reverend John Gregson in 1862. The latter's motto was ‘Watch and Be Sober’.

It was the Soldiers’ Total Abstinence Association which, in 1867, started awarding medals to its members for set periods of sobriety. This practice can still be seen today in the awards issued by Alcoholics Anonymous. Many of these medals, such as the one-year temperance award shown above, continued to be issued later by the much larger Army Temperance Association.

‘Serious crime within the Army is almost entirely due to the effects of drink.’Lieutenant-General Sir Frederick Roberts — 1888

The role of General Roberts

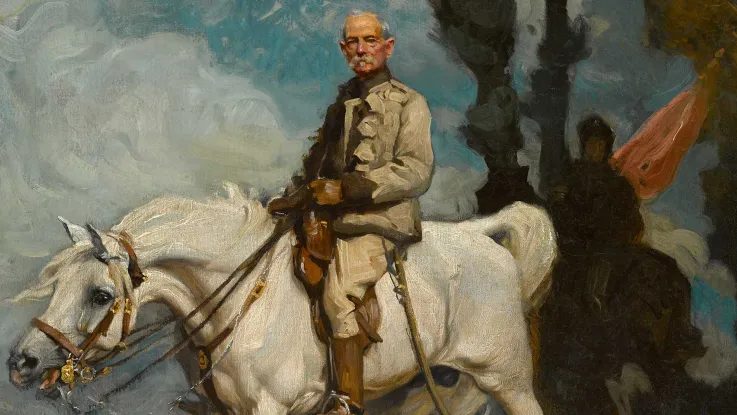

The work of Reverend Gregson and the Soldiers’ Total Abstinence Association attracted the attention of influential officers such as General Sir Frederick Roberts in the 1880s.

Following Gregson’s retirement, Roberts amalgamated the Soldiers’ Total Abstinence Association with the Outram Institute to form the Army Temperance Society (ATS) in India in 1888.

Army Temperance Association

The ongoing success of the ATS in India under Roberts’ leadership led to the creation of the Army Temperance Association (ATA) in 1893, which soon had over 70,000 members. The ATA also adopted the Soldiers’ Total Abstinence Association's motto of ‘Watch and Be Sober’.

It provided temperance institutes for its members, sponsored a wide range of sporting activities and promoted regimental campaigns towards sobriety. It continued awarding medals, such as that for three years' temperance, shown below.

The ATA’s cross for six months' temperance was originally thought to have been named in honour of the artist George Cruickshank and his work highlighting the perils of alcohol. However, it more likely referred to Colonel Arthur Crookshank, a President of the Soldiers' Total Abstinence Association, who was killed in 1888 during the Hazara Expedition.

Good character

The Army Temperance Association continued with the approach used by its Indian predecessors. But it also helped its members to find work once they retired from the Army, ensuring that their good character and temperate habits were made known.

The effectiveness of the ATA was widely publicised in the British press during the 1890s and early 1900s, with impressive statistics being quoted. In 1898, for example, nine times as many non-abstainers were court-martialled compared to their abstinent counterparts. It was also reported that the number of abstainers admitted to hospital with conditions such as fever and dysentery was next to nothing.

During the Boer War (1899-1902), both Lord Roberts and Lord Kitchener praised the sobriety of the Army and partly attributed its successes in South Africa to an increase in temperance.

Royal recognition

After the Boer War, in 1902, the ATA was granted a Royal prefix. That year, it was also claimed that 25 per cent of home-stationed soldiers, and 40 per cent in India, were members of the Royal Army Temperance Association.

The Association also recognised the leadership and advocacy of Lord Roberts by naming their award for 10 years' temperance after him.

First World War

The ATA continued its campaign during the First World War (1914-18). But the presence of temperance campaigners and other 'do-gooders' behind the lines in the rest areas of the Western Front was not always welcomed by officers and men.

Many understood that alcohol, along with tobacco, could play an important role in offering relief from physical and psychological stress. Indeed, both were issued to men as part of their rations.

Decline

The Association’s membership later declined as more alcohol-free recreation opportunities became available to soldiers. The religious commitment that had inspired many 19th-century temperance campaigns also abated.

The establishment of the Navy, Army and Air Force Institutes (NAAFI) and their provision for service personnel, along with wider societal changes in attitudes towards alcohol, further decreased membership. The ATA was finally disbanded in 1958.