State of affairs

At the start of June 1945, an escalating crisis in the Levant States (now Syria and Lebanon) brought wartime allies Britain and France to the edge of a new conflict. Catastrophe was only narrowly averted by a last-minute diplomatic solution. This was a stark illustration of the instability that so often emerged in the wake of the Second World War.

In Europe, the complexities of the peace were also becoming clear. Britain’s soldiers were part of the various Allied Control Commissions overseeing Axis territories, including Trieste and Romania.

In Germany, British troops were part of a military government tackling all manner of problems, from fixing basic utilities to hunting down Nazi war criminals. They also assumed responsibility for the millions of ‘Displaced Persons’ seeking a route home, as well as the many thousands of former prisoners of war awaiting repatriation.

Alongside these professional difficulties, Britain’s soldiers were coming to terms with the unusual social challenges of military occupation. Within weeks of VE Day, British Army commanders were forced to relax their ban on 'fraternising' with the Germans after troops routinely flouted the rules.

Amid this flurry of action, the Army was also confronting its own future. News of Japan’s eagerness to seek peace terms made it clear that the war in the East was entering its final stages. In addition, negotiations at the Simla Conference pointed towards a declining role for Britain in India.

In June 1945, the number of soldiers serving in the British Army reached 3.1 million – the largest it had been since the First World War. But with demobilisation under way, and huge changes to Britain’s international commitments on the horizon, it was inevitable that the Army's size, scope and structure would radically change in the months and years ahead.

The Levant Crisis

In late May 1945, after French troops had responded with force to nationalist protests in Syria, the British government demanded an immediate ceasefire.

When France ignored Britain’s request, Prime Minister Winston Churchill ordered British troops to invade Syria on 1 June. This intervention brought the two allies to the brink of war.

In Damascus, the Syrian capital, French troops were forced to withdraw and a truce was agreed the following day. However, a fierce war of words broke out, with the Free French leader Charles de Gaulle (pictured above) accusing Britain of betraying his nation.

The British Army would remain in Syria until July 1946.

Vienna Mission

3-13 June 1945

In early June, Major General John Winterton led a British mission to Vienna. Alongside his French, American and Soviet counterparts, Winterton was tasked with inspecting the state of Austria in preparation for the establishment of a four-power military government there.

While Austria was officially part of the Third Reich following the Anschluss of 1938, the Allies considered it the first victim of Nazism and decided that a less stringent occupation was required in comparison to Germany.

‘The Battalion, this time reinforced with the definite knowledge that it was to achieve BERLIN, polished, polished, and repolished itself for a full week. A rear party was to be left in BONN and was to deal with personnel proceeding on leave… The Battalion moved the whole day along the Autobahn to the staging area where it was to join up with the main body of the British occupational force on its way to BERLIN.’War diary of 1st Battalion, Grenadier Guards — 19-26 June

Berlin Declaration

5 June 1945

In Berlin, representatives of Britain, the USA, the Soviet Union and France signed a declaration ratifying their supreme authority over Germany. It proclaimed the intention of the Allies to work together as part of a four-power administration based in the German capital.

This marked the commencement of a military occupation, with British troops retreating from the line of contact to their own occupation zone in the north-west.

At the end of the month, British soldiers prepared to enter Berlin. The city was also divided between the four powers, despite being located deep inside the Soviet zone.

‘Wed 6-6-45. Anniversary of D-Day so Isenhower [sic] gave us a day off. Got up for breakfast at 8.00 and then went back to bed & had a sleep till 12.00… Went to the Metropole cinema & then to Monty’s [Club] for tea.’Diary of Private Cecil May, Royal Army Service Corps, Brussels, Belgium — 6 June 1945

Operation Exodus

Since April 1945, the Royal Air Force had overseen the airborne repatriation of former prisoners of war in Europe. By June, around 3,500 flights had brought 75,000 men back to Britain in modified Lancaster bombers.

‘I am directed to state that official notification of the arrival in this country of Lieutenant T. R. Hall, Royal Engineers, has been received with pleasure. It is regretted that, in the prevailing circumstances, it was not possible to give you advance notice of his liberation by the Allied Forces.’War Office letter informing the family of Lieutenant Timothy Hall about his return home from Stalag VII-A prisoner-of-war camp in Germany — 6 June

Occupation of Austria

At midday on 8 June, members of the 78th Division crossed the border with Austria. Like in Germany, they were preparing to take part in a military occupation. British forces would govern a zone in the south-east of the country, as well as a sector of the capital, Vienna.

The images above show members of the Military Police patrolling the Austrian-Italian border and soldiers of the Reconnaissance Corps enjoying a cup of tea in the town of Trebesing.

Farewell to Armour

9 June 1945

On 9 June, the Grenadier Guards took part in a large ‘Farewell to Armour’ parade on Rotenburg Airfield in Germany. It marked the reorganisation of the Guards Armoured Division into a purely infantry role.

This is illustrative of a broader shift in the structure of the British Army at the end of the war in Europe. In the main, the army of occupation prioritised skilled personnel over tanks.

British Element Trieste Forces

In early May 1945, Yugoslavian Partisans and soldiers of the New Zealand Military Forces had jointly fought to capture Trieste in north-eastern Italy.

On 9 June, an agreement was reached for the establishment of an Allied military government of Trieste. It saw British troops, including Driver Ray Lamb (pictured above), relocate to the city as part of occupation forces.

The British Army remained in Trieste until 1954, when the territory was split between Italy and Yugoslavia.

Allied Control Commission (Romania)

In late 1944, King Michael of Romania had launched a coup against the pro-Nazi Romanian government and led his country to join the Allies.

Soon after, Soviet forces occupied Romania and established a tripartite Allied Control Commission, which included British and American representatives. Among them was Major Nigel Gunnis of the Royal Artillery, pictured above (front right) at Lake Snagov in June 1945 alongside King Michael and his partner, Dolly Steriopol.

During this period, Michael appointed a pro-Communist government but later went on ‘royal strike’ in opposition to its policies.

Like in much of Europe, the fate of Romania rested upon a peace treaty that was finally signed in 1947. At that point, the country’s monarchy was abolished, British and other Allied soldiers left, and Romania became a republic.

Non-fraternisation in occupied Germany

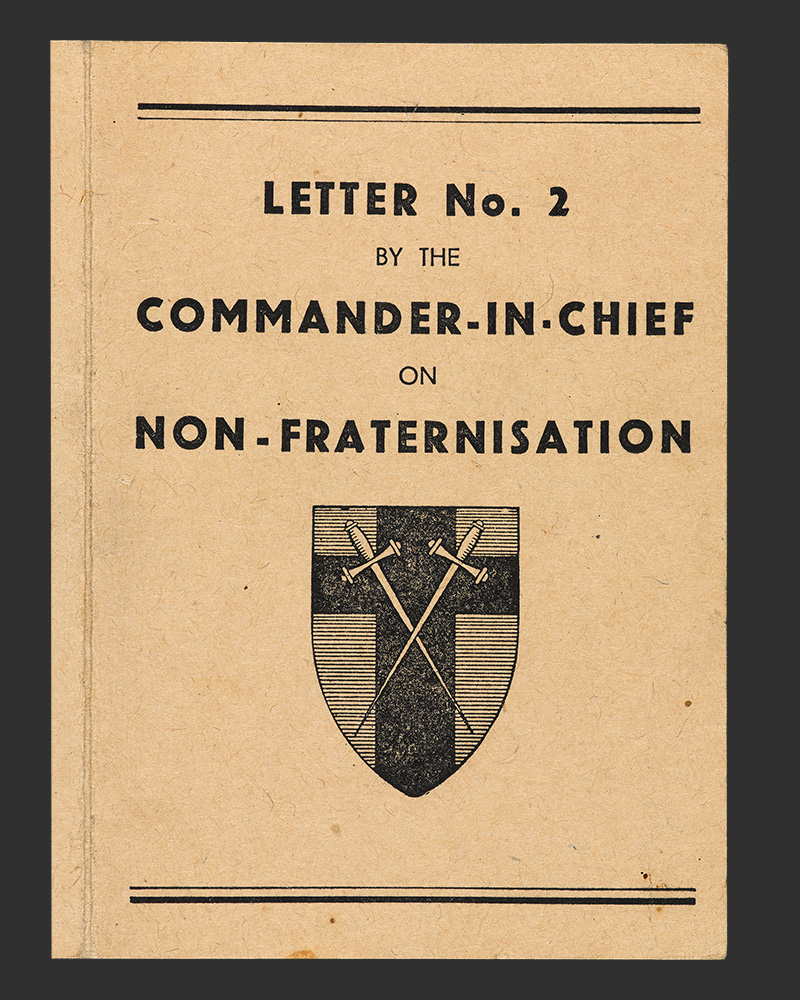

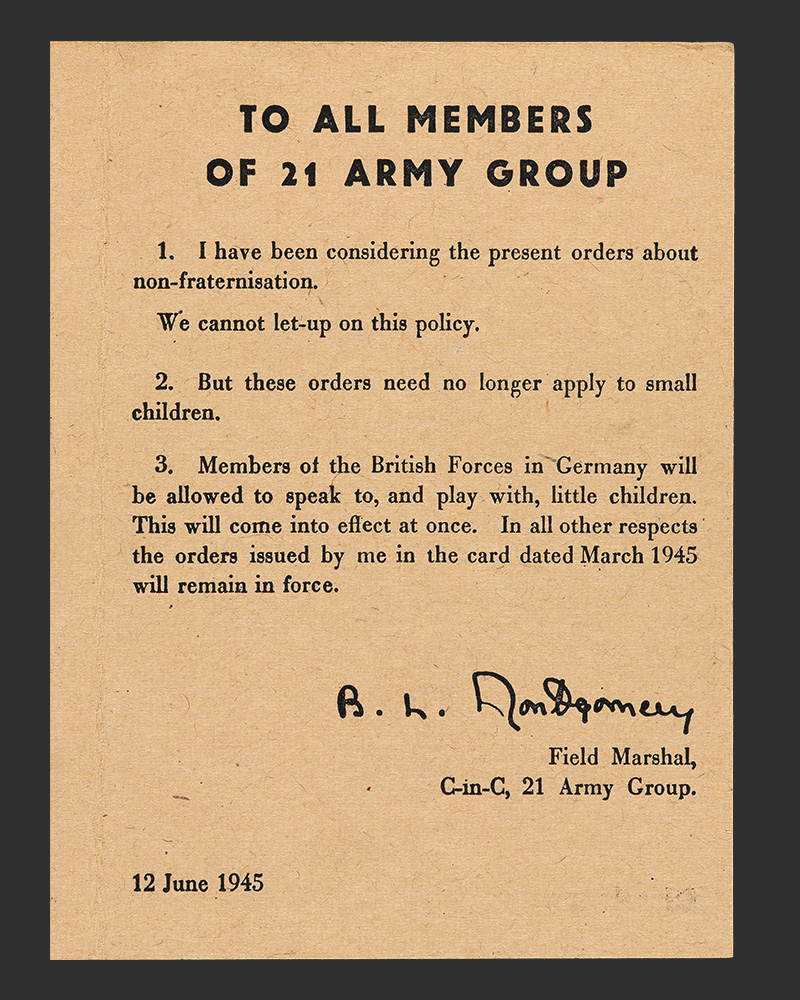

When British troops first entered Germany, Field Marshal Montgomery sent an unequivocal message to the men of the 21st Army Group: ‘You must keep clear of Germans – man, woman and child – unless you meet them in the course of duty... In short, you must not fraternise with the Germans at all.’

But in the first weeks of the military occupation, the reality had proven rather different. British soldiers routinely broke the rules in their liaisons with local civilians, ranging from ordinary friendships to sexual relationships.

When news of this so-called ‘fratting’ reached Britain, it caused quite a stir among the general public, many of whom expected an unforgiving attitude towards their defeated foe.

‘We have been flooded with kids to-day from local farms and I am afraid I couldn’t keep up the non-fraternization with them. They were all youngsters, 5, 6, 7, 8, and such bonny kids, they kept jawing away and playing games around the caravan, and trying to cadge chocolate. As we had our food they stood around watching every mouthful… and were highly delighted when we gave them a bit each.’Sergeant Samuel Bates, Royal Signals, Germany

‘In our new area, the Battalion is very scattered, but everyone is very comfortable and, if only the weather would settle down, we should all be very satisfied to remain here a long time. Battalion Headquarters is at a brick factory and we occupy the house of the manager, while he and his family, one wounded son and three daughters, live in the attic. Martin HOWARD assures me they are charming, though his relations with them could hardly be called ‘fraternising’, as he took them up to see photographs of BELSEN and DACHAU concentration camps to let them see something of the Nazi Regime.’War diary, Grenadier Guards — June 1945

British Royal Warrant Trials

On 14 June, a Royal Warrant established British military courts to try war criminals in the British Zone of occupation in Germany. These hearings could impose a range of sentences, including the death penalty, against anyone found guilty of war crimes during the Second World War.

Britain prepares to vote

On 15 June, the British Parliament was formally dissolved ahead of a general election to be held on 5 July.

With the collapse of the wartime coalition, Labour’s Clement Attlee (seen above meeting Indian Army troops) faced off against the Conservative leader, Winston Churchill. British soldiers stationed across the world were all entitled to cast their ballot.

Army hits wartime peak

In June 1945, the British Army reached 3.1 million serving personnel, its greatest size at any point during the Second World War. This included men and women from across the British Empire, the Commonwealth and other European nations.

Demobilisation gets under way

On 18 June, the demobilisation of Britain’s armed forces began. Most were to be released according to their 'age-and-service number', which was calculated from their age and the months they had served.

Those returning to jobs that were deemed vital to postwar reconstruction were released early. Women who were married and men aged 50 or more were also given priority.

Decommissioned soldiers received a one-time grant of £83 cash and a set of civilian clothes, including the so-called ‘demob suit’ (pictured above), as well as shirts, underclothes, raincoats, a hat and shoes.

The Long Road Home

For many British troops, the prospect of demobilisation was very welcome – a return to family, friends and ‘normality’ at long last.

But the reality sometimes proved rather different. After years away, ex-soldiers often suffered from the physical or psychological scars of war and struggled to adapt to civilian life away from the Army routine.

Sometimes, personal relationships lay in tatters after years apart, while some veterans felt a sense of disenchantment with life in postwar Britain.

Demob-happy

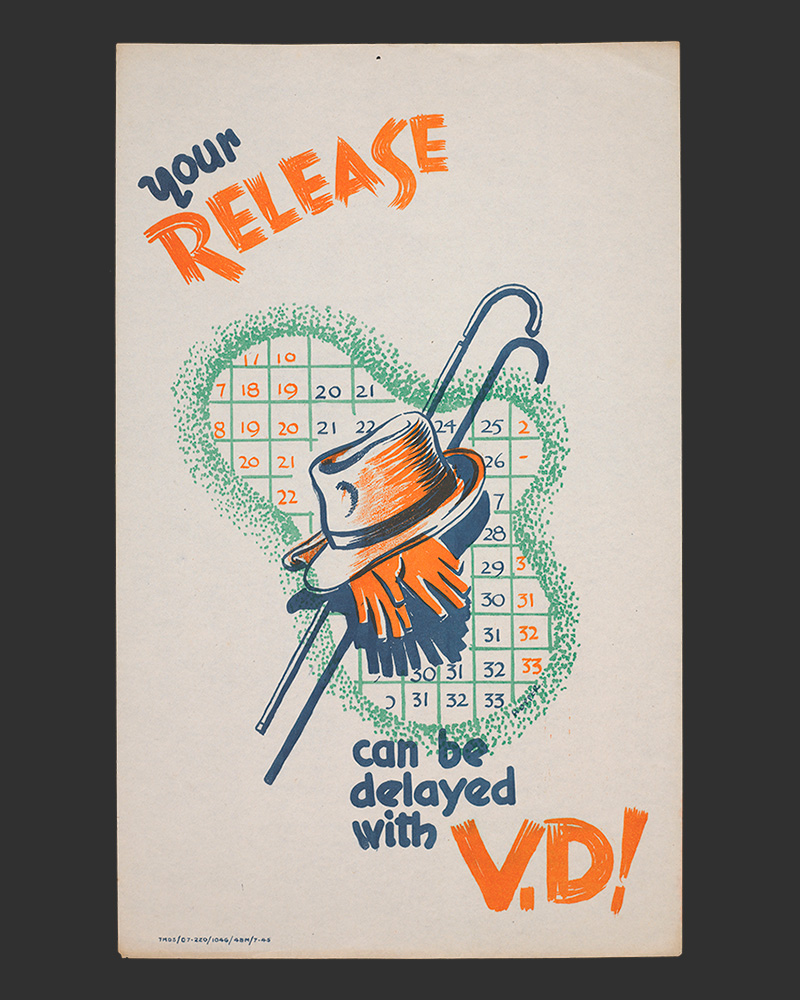

In the summer of 1945, as millions of British soldiers awaited their ticket home, the Army authorities struggled to maintain discipline in the ranks.

One of the main indicators of a ‘demob-happy’ atmosphere was a rapid rise in sexually transmitted infections. As this official poster warned, a positive test could delay demobilisation for weeks or months.

(Image courtesy of IWM)

Allied victory parade in Rangoon

15 June 1945

On 15 June, an Allied victory parade was held in Rangoon (now Yangon), the capital of Burma (now Myanmar). The Supreme Allied Commander, Admiral the Lord Louis Mountbatten, is shown above taking the salute.

British Indian Army troops, who had been so essential to the Burma campaign, were at the heart of the celebrations.

Japan seeks peace

22 June 1945

On 22 June, American forces finally captured the island of Okinawa after a bloody and prolonged battle.

The same day, Emperor Hirohito of Japan declared his intention to seek peace talks with the Allies: ‘I desire that concrete plans to end the war, unhampered by existing policy, be speedily studied and that efforts made to implement them.’

Simla Conference, India

On 25 June, the Viceroy of India, Lord Wavell, met with the major political leaders of British India at the Viceregal Lodge in Simla, the summer capital. The conference discussed the proposal for a new executive council and constitution for India after the end of the war.

While the talks failed to produce any significant results, it was becoming clear that India was likely to gain its independence from Britain in the near future.

A changing army

As the war came to an end, the British Army underwent significant organisational changes. After a brief period as part of the army of occupation in Germany, No 3 Commando (pictured disembarking at Tilbury Docks in June 1945) was disbanded shortly after its return to the British Isles. It was one of countless units to be reorganised, reequipped or broken up in the course of mass demobilisation.

‘There is a lot of admin work to be done & I do some of it. I have all the typing to do, which is really rather good except that the typewriter looks as if it is a relic from the stone age. I have to do the pay for the Platoon, all the leave warrants, ration cards etc, the billeting allowances & various other things. They aren’t terribly busy here though. We have a 36 hours [leave pass] every weekend… This really isn’t much good to me as I am going to get bored if I have got 36 hours to mess about in.’A letter from Private Audrey Hayward, Auxiliary Territorial Service, to her mother, London — 26 June 1945

(Image courtesy of the US National Archives)

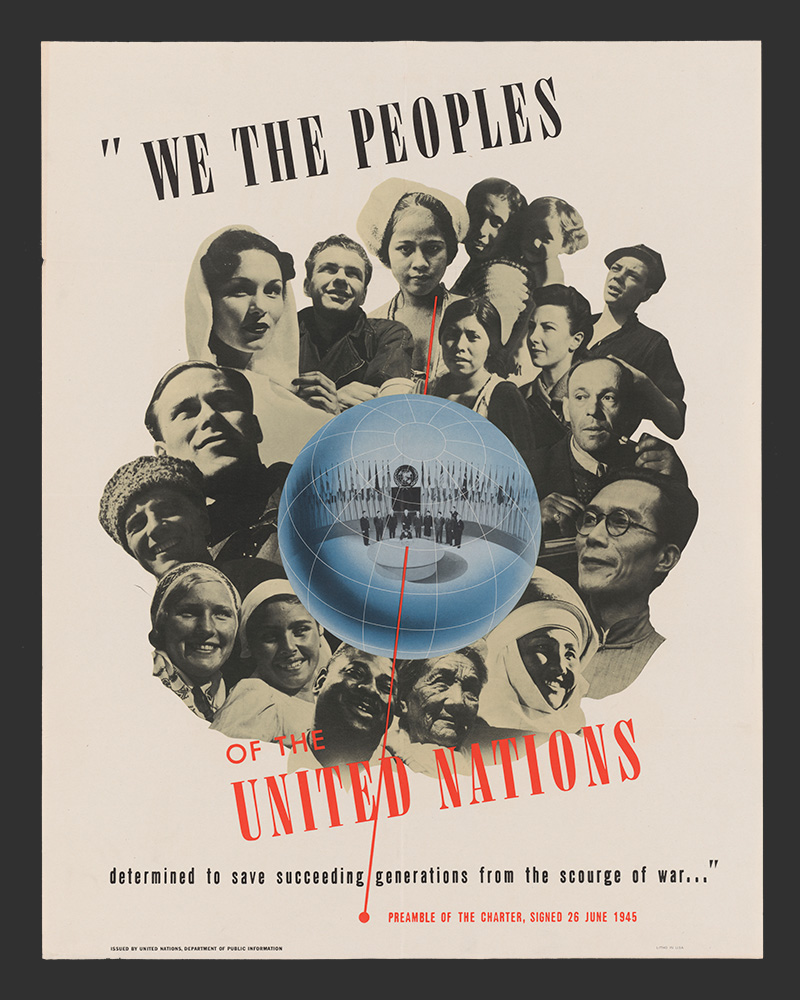

United Nations Charter

26 June 1945

On 26 June, 50 of the 51 original United Nations (UN) members signed the UN Charter at the San Francisco War Memorial and Performing Arts Center. Poland had no generally recognised government at the time of the conference, but would belatedly sign the document in October.

The charter declared that the UN and its member states would: maintain international peace and security; uphold international law; achieve ‘higher standards of living’ for their citizens; address ‘economic, social, health and related problems’; and promote ‘universal respect for, and observance of, human rights and fundamental freedoms for all without distinction as to race, sex, language or religion’.

Army tourism

In an era before overseas travel became affordable to the masses, serving in the armed forces was one way for people to see the world.

In 1945, British troops were stationed all over the globe, including various parts of mainland Europe. As the fighting came to an end, many soldiers took advantage of the opportunity for excursions to all kinds of touristic sites.

From the British Zone in Germany, weekend trips to Scandinavia or other parts of Western Europe were easy, cheap and often full of unexpected delights.

‘I said we fed on ‘rations’, but what rations? Not British army rations. All sorts of good things like bacon and eggs, scrambled eggs oozing real butter, a rich and excellent cuisine, good sauces, strawberries and whipped cream. Things like bread and butter are rationed, but the ration seems lavish!’Lieutenant Colonel Harold Newman, describing his trip to Denmark as part of the Survey Branch of 21st Army Group HQ — 27 June 1945

Displaced Persons

In the weeks after VE Day, the Allies repatriated over 5 million ‘Displaced Persons’ (DPs) of all nations. These were refugees, including former forced labourers and Holocaust survivors, left stranded across Europe.

For many, there was no longer a home to return to. Bands of DPs were left roaming the countryside looking for food, shelter or retribution. This led to the establishment of ‘DP camps’ in Germany and beyond, where these civilians could live while awaiting resettlement.

Polish DPs in Germany

During the Nazi occupation of Poland, millions of Polish civilians were transported to Germany as forced labourers or victims of the Holocaust.

In theory, surviving Polish DPs (some of whom are pictured) were now able to return home. But political uncertainty in Poland made this difficult or undesirable for many. Their fate remained uncertain.

‘Our Occupational duties here are very light as there are no GERMAN troops and our only trouble is with the Displaced Persons, mostly RUSSIANS and POLES.’War diary, Grenadier Guards, Diepholz, Germany — 6 June 1945

Provisional Government in Poland

On 28 June, a Soviet-backed provisional government came to power in Poland, despite opposition from the Polish government-in-exile based in London. This was emblematic of the uncertain fate of Eastern Europe in the aftermath of the Second World War.

In early July, both Britain and the United States recognised the new Polish government. The existing Polish Armed Forces, serving under British command, were soon disbanded. The following year, the Polish Resettlement Corps was formed to help more than 150,000 former Polish service personnel return to civilian life in Britain rather than return to communist Poland.

On This Day: 1945

This is the sixth instalment of a series exploring the British Army's role in 1945 – one of the most decisive years in modern history – drawing upon the National Army Museum's vast collection of objects, photographs and personal testimonies.

Throughout 2025, a new instalment will be released each month that focuses on events from 80 years beforehand. The series will highlight the everyday experiences of Britain’s soldiers alongside events of grand historical significance.