Gerry Chester, during training with the Royal Tank Regiment, c1942 (Image courtesy of the Reverend Philip Chester)

Joining up

Gerry Chester from Wallasey on Merseyside got his first taste of Army life in 1940, when he joined his local ‘Home Guard’ unit. This role gave him his first experience of drill and weaponry, but was enough to convince him that the infantry was not for him.

To avoid being conscripted into an infantry regiment, Chester went to join up as a volunteer in September 1941 at the age of 19. Enticed by a recruiting poster depicting black-bereted soldiers of the Royal Tank Regiment, he opted to become a tankman.

Tank training, Cambridgeshire, 1940

Top of the class

Chester’s basic training was undertaken at Warminster in Wiltshire. To his surprise, he found that one of his training sergeants was his footballing hero William ‘Dixie’ Dean. Dean was one of the greatest centre-forwards of his era and Chester had seen him play many times for his local team, Everton.

Alongside drill and a gruelling regime of physical training, Chester and his fellow recruits began the specialist training required for armoured warfare. Showing an aptitude for this work, Chester was trained a driver operator, the highest skilled and best paid role available.

His principal job was to act as wireless operator, but he was also qualified to drive a tank or even to take command of it should the need arise. His talent and enthusiasm enabled him to pass out as all-round top of his class of recruits.

‘Despite all the moaning and groaning, the efforts of the APTC [Army Physical Training Corps] crew paid dividends. As a result, by the time we were ready for posting, we were no longer considered to be "miserable specimens".’Gerry Chester on his basic training

North Irish Horse

Chester was then posted to the North Irish Horse at Ogborn St George in Wiltshire.

Like all cavalry regiments in the British Army, the North Irish Horse had been mechanised after the First World War. However, due to their origins on horseback, they were looked down upon by some members of the Royal Tank Regiment. Indeed, Chester’s commanding officer announced this posting with some derision.

This parochial attitude was of no consequence to Chester. Although one of only a handful of English recruits to this Irish unit, he was delighted by the warm reception he received into the regiment which was to become his home and family for the next four years.

Cap badge, North Irish Horse, c1940

‘Men, I have some bad news for you. You are being posted to the North Irish Horse, damned donkey wallopers!’Gerry Chester’s training officer announcing his posting to the North Irish Horse

Churchill tank

The North Irish Horse was equipped with the latest Churchill tanks. The Churchill had been blighted with mechanical problems during its development, but would ultimately prove to be a highly versatile and effective vehicle.

Designed for an infantry support role, the Churchill had only a slow speed, but it was heavily armoured and roomy compared to other tanks. It was also highly adaptable, enabling many variants to be produced. These included those used for bridge laying and beach crossing, and those that mounted specialist assault weapons such as flame throwers and howitzers.

The Churchill also had a remarkable climbing ability. This enabled it to traverse difficult terrain and earned it the nickname ‘the mountain goat’.

Throughout 1942, Chester and his regiment undertook training with this tank at various sites in the West Country and East Anglia.

Churchill tank, c1944

North Africa

In 1943, the regiment was mobilised for active service overseas. The men landed in Algeria on 1 February. Here, they were to take part in the final phase of the campaign in North Africa against the Axis forces of Germany and Italy, who were fighting a desperate rearguard battle in Tunisia against Allied forces advancing from both east and west.

Despite their many difficulties, the Axis were still a formidable foe. Under the command of Field Marshall Erwin Rommel - the famous ‘Desert Fox’ - the Germans had just undertaken a successful counter-attack at the Kasserine Pass. They were now poised to exploit this success and achieve a major breakthrough.

A captured German Tiger tank, Tunisia, 1943 (© IWM NA 2640)

First combat actions

The North Irish Horse was deployed to Béja in Tunisia to counter this threat. And it was here that the men had their first taste of battle.

After a long advance over difficult terrain in appalling weather, they arrived just in time to meet a powerful German armoured assault. The German force included a contingent of their formidable new Tiger tanks. This was one of the first times that the western Allies had encountered this 60-tonne monster.

After beating off this attack, they were immediately called upon to meet another enemy thrust nearby at Hunt’s Gap. Further fighting took place here, before the Germans were halted once again.

Sadly, these victories came at the expense of the regiment’s first battle casualties, including Chester’s much-loved squadron commander, Major John Rew.

‘Sadly ‘A’ Squadron OC, Major Ketchell, had his tank knocked out killing both the operator, Sgt Walters, and the gunner, Trooper Nursey. On receiving this news shockwaves hit us all – we were no longer playing War Games!’Gerry Chester on the regiment’s first casualties at Béja, 1943

A nasty shock

The Allies now resumed their advance toward the city of Tunis, their ultimate objective.

During an operation to clear Djebel Abiod at the end of March, Chester had a nasty shock. While surveying the landscape, the glinting light from the lens of his binoculars attracted the attention of an enemy sniper, who took a shot at him.

The bullet shattered his binoculars, spraying his face with splinters and taking a chunk out of his nose. He suffered no serious harm, but the injury was compounded by a nasty illness, and Chester was hospitalised for several weeks. For the rest of his life, the scar on his nose reminded him of this incident.

Churchill tanks of the North Irish Horse supporting the attack on Longstop Hill, 1943

The Battle of Longstop Hill

The campaign culminated in April at the Battle of Longstop Hill. Here, the Churchill tanks proved their worth. Their remarkable climbing ability enabled them to scale the hill and overrun positions the enemy had believed to be completely inaccessible to tanks.

This victory opened the path to Tunis and helped bring about a decisive victory for the Allies in North Africa. It also helped to ensure the continued production of the Churchill, which had been due to be retired that year.

‘Impossible that anyone could get up there’

Interviewed in 2012, Gerry Chester recounts the assault on Longstop Hill in April 1943.

New kit

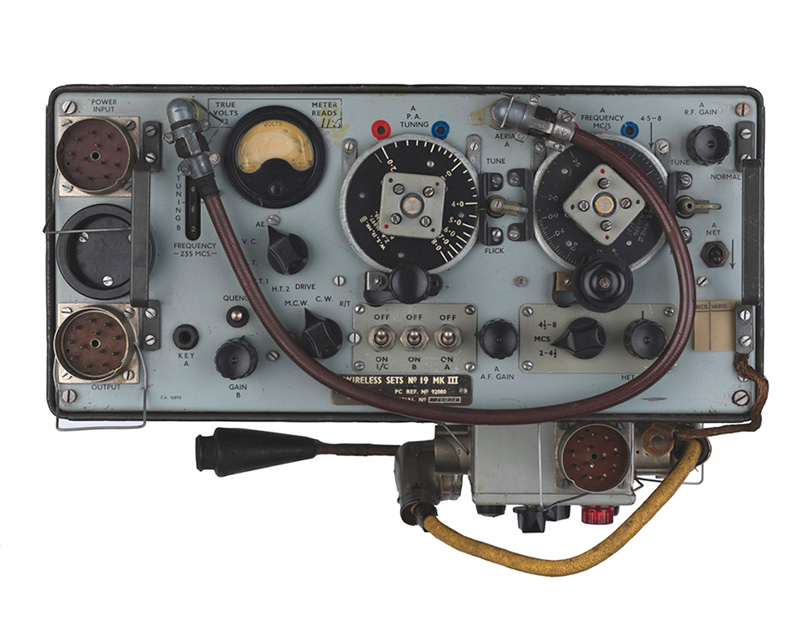

The regiment remained in Africa for many months. During this time, Chester was promoted to corporal and was posted to Constantine (now Qacentina) in Algeria. Here, he received training in the latest No 19 Wireless Set, with which his unit's tanks were now to be equipped.

This radio was highly versatile, enabling three levels of communication. An A-set provided communication at squadron and regimental level, a B-set provided inter-tank communication, and an internal channel enabled communication between crew members. This system would enhance the regiment’s performance in battle.

However, to maintain its effectiveness, a careful process, known as ‘netting’, had to be undertaken frequently to ensure that all wirelesses were on the same wavelength. ‘Netting’ would become one of Chester’s most important routine jobs.

No 19 Wireless Set, 1943

‘Although much of the course was devoted to the less practical matters, such as circuitry and valve function, it was one that I thoroughly enjoyed. One thing I learnt never to be forgotten was that the B-set was a “self-excited, super-regenerative, local oscillator”.’Gerry Chester on training with the No 19 Wireless Set

The Hitler Line

In 1944, the North Irish Horse was deployed to Italy, where the Allies were fighting a protracted campaign against the Germans. On 23 May, it took part in an assault on the ‘Hitler Line’, a defensive position running through the Aurunci mountains, south of Rome.

Chester’s tank was placed in the vanguard of the attack. It was quickly knocked out by anti-tank fire, leaving one of the crew dead and their tank commander severely wounded. Chester was lightly wounded, but he and the other surviving crew members were able to escape and carry their stricken officer to safety. Chester was later honoured with a mention in despatches for this action.

The battle cost the North Irish Horse 36 officers and men killed, 36 wounded and 32 tanks destroyed. This was the bloodiest day in the regiment’s history and was later commemorated by a special regimental parade held each year in Belfast.

Infantry and tanks moving up to the Hitler Line, May 1944

Chester and his crew on their tank, 'Ballyrashane', c1944 (Image courtesy of the Reverend Philip Chester)

‘He thanked us for saving his life’

Interviewed in 2012, Gerry Chester describes the time his tank was knocked out during the assault on the Hitler Line in May 1944.

Tough terrain

Chester and his unit continued to support the Allied drive northwards. During this advance, they broke through a series of German positions. A notable success was an assault on the Incontro Monastery in early August, where the climbing capability of the Churchill once again proved invaluable.

Italy’s mountainous terrain could still proved treacherous at times. Later that month, during their approach to the German’s Gothic Line defences in the northern Apennines, one of their tanks tumbled 200 feet into a ravine, killing one man and seriously wounding three others.

Crossing Italy’s many rivers could also prove problematic. This was aggravated by the heavy rain that fell during the autumn and winter of 1944.

A tank bogged down in a river in Italy, 1943

Regimental historian

Chester continued with his unit until April 1945, when he was granted a well-earned period of leave. He returned to Italy later that year and was then stationed in Austria and Germany as part of the Allied occupation forces. He left the Army at the end of 1946 and went on to work for Imperial Chemicals.

Later in life, he took a passionate interest in the history of his regiment. He diligently compiled a series of volumes which record a range of regimental information relating to its service in the two world wars. These volumes serve as a valuable historical resource and a fitting memorial to this remarkable tankman.