State of affairs

On 2 September 1945, the Second World War officially ended with the Japanese government’s formal surrender aboard the USS ‘Missouri’ in Tokyo Bay. Immediately, it became clear that questions over the future of the British Empire would dominate postwar affairs in Asia and beyond.

Already in September, Japan’s defeat had brought simmering tensions in Southeast Asia to a head. In French Indochina (now Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos) and Malaya (now Malaysia), the prospect of a return to European colonialism inspired popular resistance.

In both cases, the British Army was involved in efforts to restore order and ultimately reinstate imperial control. Conversely, Britain now explicitly promised a pathway to independence for its own colonial possessions in India.

In Europe, the work of reconstruction was well underway. British soldiers were assigned all manner of tasks, ranging from rebuilding physical infrastructure and clearing spent munitions to restarting schools.

Some of the most challenging assignments were in Germany, where the Allied military government was now in full swing. From the trial of Nazi war criminals to the ‘re-education’ of the general population, the Allies attempted to implement the Potsdam Agreement amid the chaos and disorder that characterised much of this postwar world.

‘It is our duty to understand each other, what the differences and interests may be, so that all those who died on the battlefield and elsewhere did not give their lives in vain. You’ve lost the bridge at Arnhem but you and the other men of the 1st Airborne Division have built another one at Apeldoorn, a bridge of mutual appreciation.’Letter from Dr Pilaar, a Dutch civilian doctor, to Captain Timothy Romilly, 1st Parachute Squadron, Royal Engineers - Romilly had been wounded and captured at Arnhem in 1944, but had since returned to the UK — 1 September 1945

Second World War officially ends

2 September 1945

After six years, the Second World War formally came to an end with the signing of the Japanese Instrument of Surrender aboard the USS 'Missouri' in Tokyo Bay.

In mid-August, the news of Japan’s intention to surrender had inspired large celebrations in Britain and around the world.

XIII Corps says ‘Finito!’ to fighting

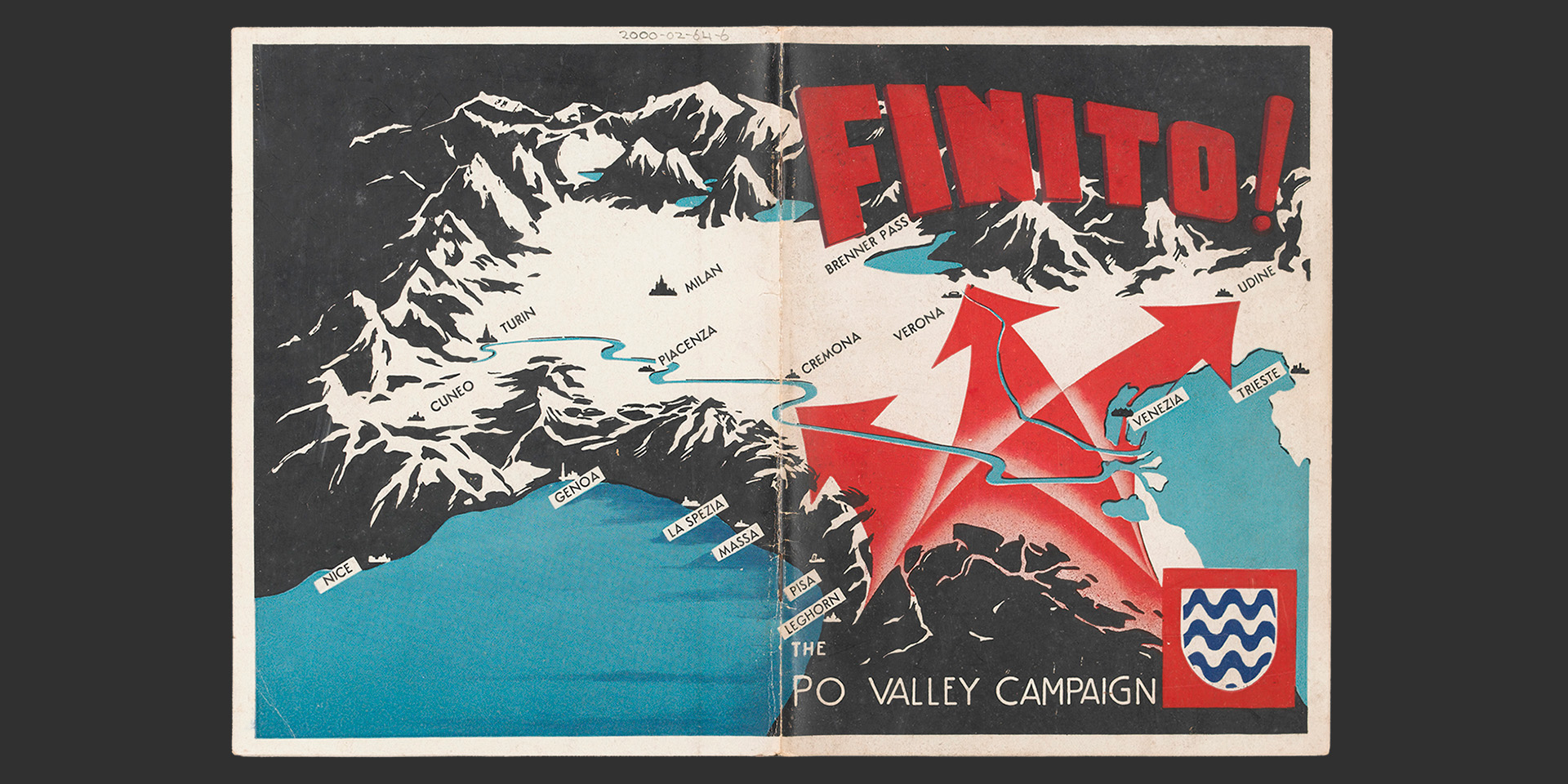

This stylised map was produced as part of the official programme for the XIII Corps Searchlight Tattoo, held in Trieste in September 1945.

The map shows XIII Corps's advance through northern Italy as part of the US Fifth Army during the final stages of the Second World War, prior to its return to the Eighth Army and occupation duties in Trieste.

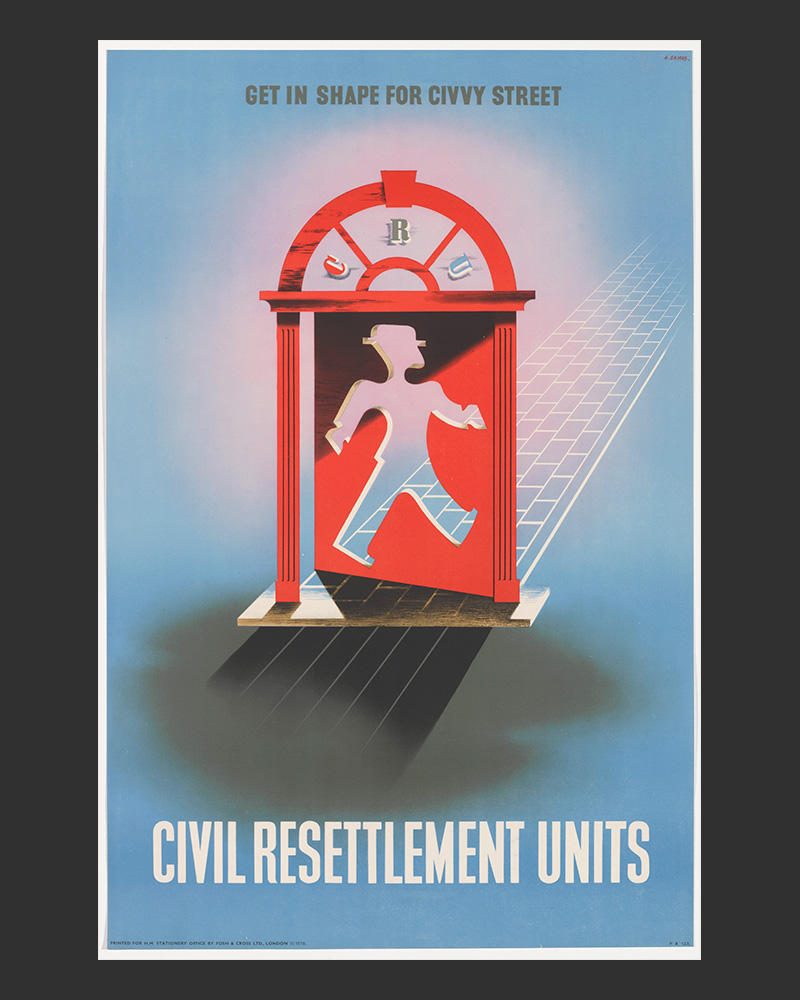

Get in shape for civvy street

Many British troops were impatient to be demobilised so they could return home. But the process was long and cumbersome.

This was partly by design as the government was keen to avoid a repeat of the mass unemployment that had occurred after the First World War. At the same time, logistical difficulties and delays were a source of frustration.

‘Anyone who has served in the Army knows the kind of discussion which follows the introduction of any new thing, whether it is the promotion of a new lance-corporal, the announcement that the unit is going to move, or the introduction of a new shade of blanco. The pros and cons are pretty thoroughly talked over in the barrack-room as soon as anything happens. The release of the early age and Service groups stirred up plenty of discussion about what it’s going to be like in Civvy Street, and among other things just what happens when the soldier goes through the Release machinery.’‘We All Go the Same Way Home’, Brigadier JV Faviell, Deputy Director of Recruiting and Demobilisation — September 1945

Image courtesy of IWM

Berlin Victory Parade

On 7 September, the four Allied occupiers (Britain, France, the USA and the Soviet Union) held a grand victory parade in the German capital.

Above, British Sexton self-propelled guns are pictured on the parade route.

Japanese forces surrender in Southeast Asia and the Pacific

On 12 September, General Seishiro Itagaki surrendered to Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten, Supreme Allied Commander in Southeast Asia, at the Municipal Building in Singapore.

This formal ceremony (pictured above) came six days after the surrender of Japanese forces in New Guinea, New Britain (both now part of Papua New Guinea) and the Solomon Islands aboard the British aircraft carrier HMS 'Glory' at Rabaul, New Guinea.

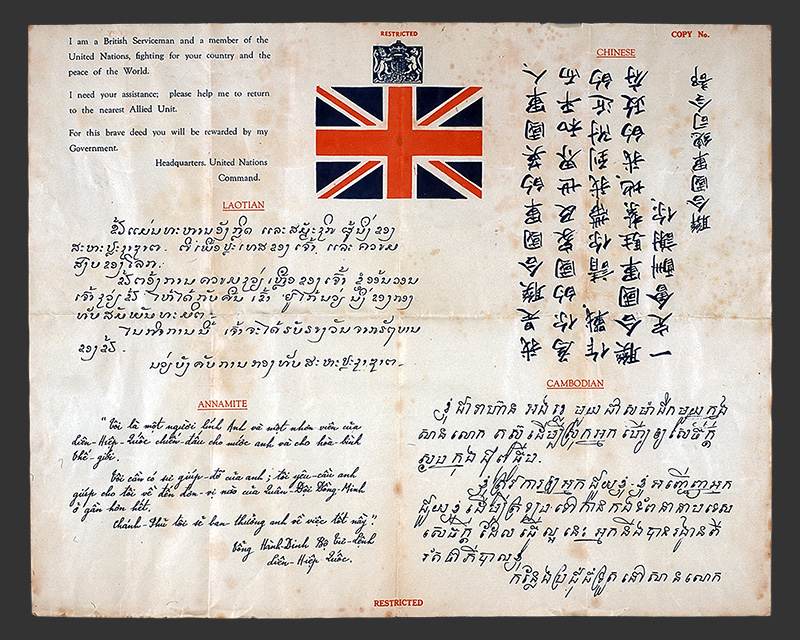

The British Army in French Indochina

On 13 September, Major General Douglas Gracey arrived in Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam) to receive the surrender of the Japanese garrison.

He encountered a febrile political situation. Eleven days earlier, Ho Chi Minh, the leader of the Vietnamese independence movement (Viet Minh), had proclaimed the Democratic Republic of Vietnam’s independence from France.

Upon Gracey’s arrival in Saigon, he ordered troops of the 20th Indian Division to relieve Viet Minh soldiers from key positions around the city. These strategic locations were then handed over to rearmed French colonial soldiers.

This intervention led to battles with members of the Viet Minh across French Indochina (now Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos). Over the course of the next six months, 40 members of the British forces and more than 2,500 Vietnamese fighters were killed.

The success of the combined Franco-British offensive (which also included the deployment of rearmed Japanese soldiers) forced the Viet Minh to retreat to the countryside.

Following the withdrawal of British forces in the summer of 1946, the Vietnamese independence movement instigated a protracted and ultimately successful guerrilla war against France that lasted until 1954.

Prisoners of war

Following the rapid advance of Japanese forces in 1941-42, around 67,000 British service personnel were taken as prisoners of war (POWs).

Conditions varied, but many of them were treated terribly and made to undertake gruelling labour details. The overall mortality rate was more than 25 per cent, seven times that experienced in German-run POW camps.

In late 1945, the survivors slowly returned home, although most did not arrive until October or later. Many carried with them the physical and psychological scars of their time in captivity.

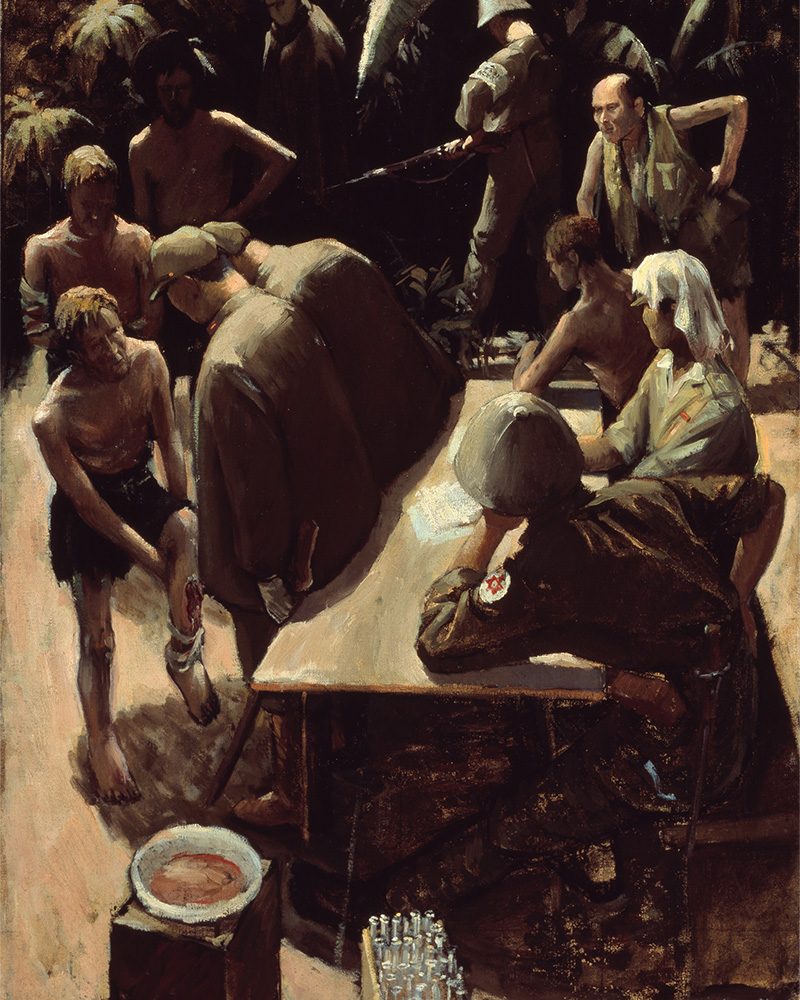

Death Railway

The painting above depicts a Japanese medical inspection at a POW hospital camp in Thailand. Those fit enough to stand were sent back to work as forced labourers on the notorious 'Death Railway' being built between Thailand and Burma (now Myanmar).

More than 10,000 British, Australian and Dutch POWs - along with even more Chinese, Malay, Tamil, Thai and Burmese civilians - died during the railway's construction.

‘Brilliant morning, the lads are on the lookout for planes again. At 10.a.m. I went for a walk to a village about 6 miles from camp, the scenery was really lovely. I got to the village at about 12.30, had a look around the village school. The kids were rather shy at first but they are soon coaxed... I had some Mochi cake with sugar and tomatoes, and about 1½ bottles of Sake (a rice wine). I got back to camp at 4.30. No sign of a plane we are disappointed again, maybe tomorrow.’Diary of Corporal Abraham Gumburd recording his time in a Japanese POW camp while awaiting his passage home — 12 September 1945

British Military Administration (Malaya) established

12 September 1945

In mid-September, British forces returned to Malaya following a period under Japanese occupation.

The British Military Administration (Malaya) was an intermediary governing authority tasked with reestablishing Britain’s control of the country, including its valuable rubber plantations. It was envisioned that the loose confederation of states known as British Malaya would ultimately be brought into a more centralised structure as part of the British Empire.

Administrators soon encountered a variety of problems, including a major economic downturn, growing crime and corruption, and an emergent communist-led national independence movement.

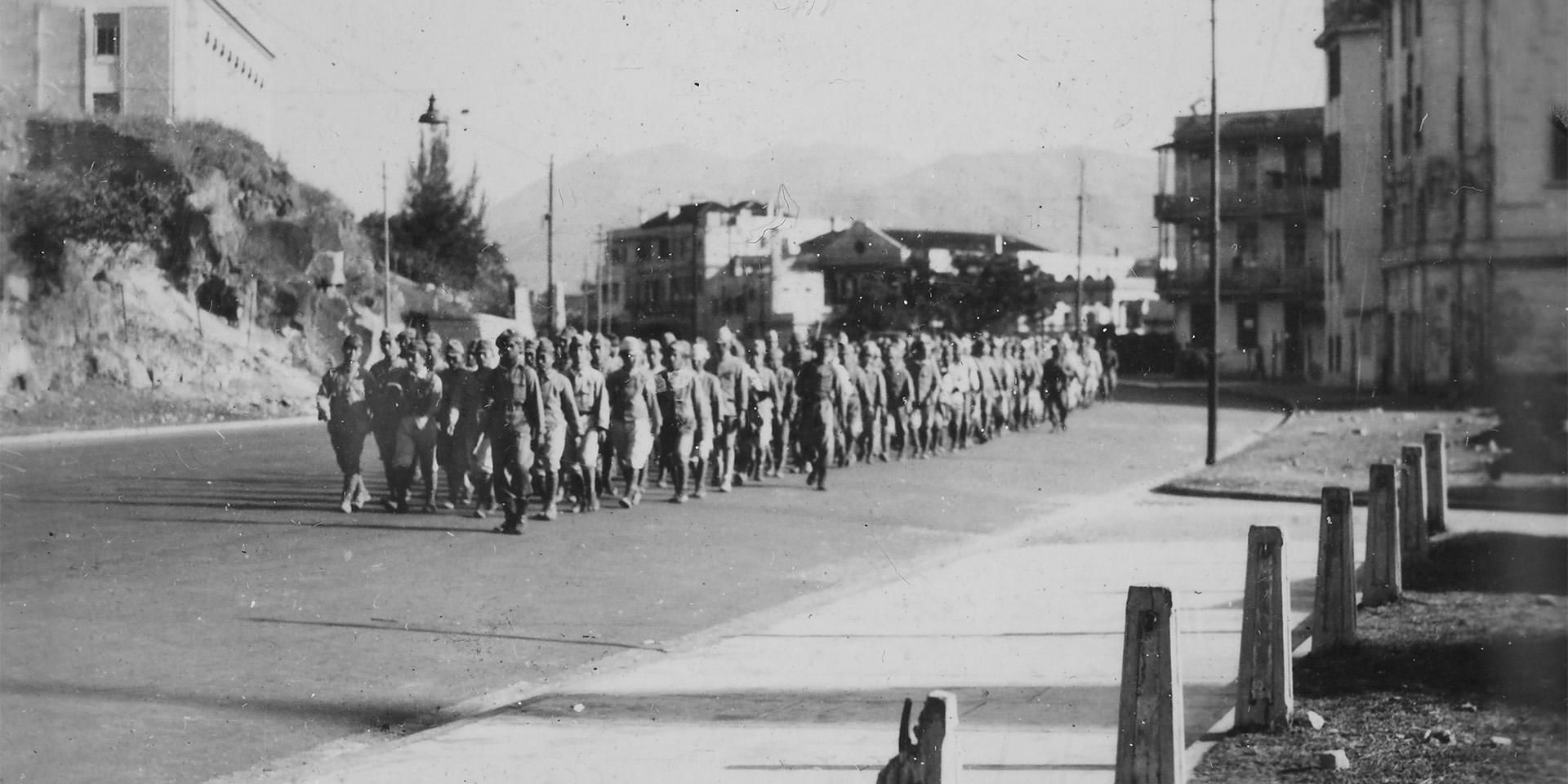

Japanese prisoners in Malaya

After the arrival of British forces in Malaya, the Japanese garrison surrendered and its soldiers were taken into captivity (pictured above).

Thousands of these Japanese POWs were transported to the islands of Rempang and Galang (in modern-day Indonesia) just south of Singapore, before their eventual repatriation to Japan.

British forces return to Hong Kong

After four years of Japanese occupation, the future of Hong Kong remained uncertain following an American pronouncement that China should assume sovereignty of the territory.

On 16 September, Rear Admiral Sir Cecil Halliday Jepson Harcourt formally accepted the surrender of Japanese forces in Hong Kong and Britain resumed colonial control.

Occupiers and occupied

With German children now exempt from non-fraternisation regulations, British troops were free to entertain inquisitive youngsters.

Despite fierce anti-German sentiment still being common among the troops, most found it hard not to sympathise with young children who had only known war and hardship.

Amid serious food shortages for German civilians, many British troops opted to share their rations.

‘Yesterday evening I was "collected"… and carted off to [a] birthday celebration in my honour… In front of my place was this “triumphal arch”, one side designed by Elizabeth (13) and the German side by Margaret aged 9, and the whole stitched by Elizabeth on her mother’s sewing machine. Margaret… made me a bookmark… Mrs Nolte had made some doughnuts from stores left behind when the U.S. troops, who had once occupied the house, moved off. They were quite nice too, and the kids, who received permission to eat as many as they liked, dug in with a vengeance.’Letter from Sergeant Samuel Bates, Royal Signals, to his wife, while based in Goslar, Germany — 15 September 1945

Belgian troops and the occupation of Germany

In September 1945, it was announced that 17,000 Belgian troops would take part in the Allied occupation of Germany from the following spring.

They were to relieve soldiers stationed in the southernmost part of the British occupation zone.

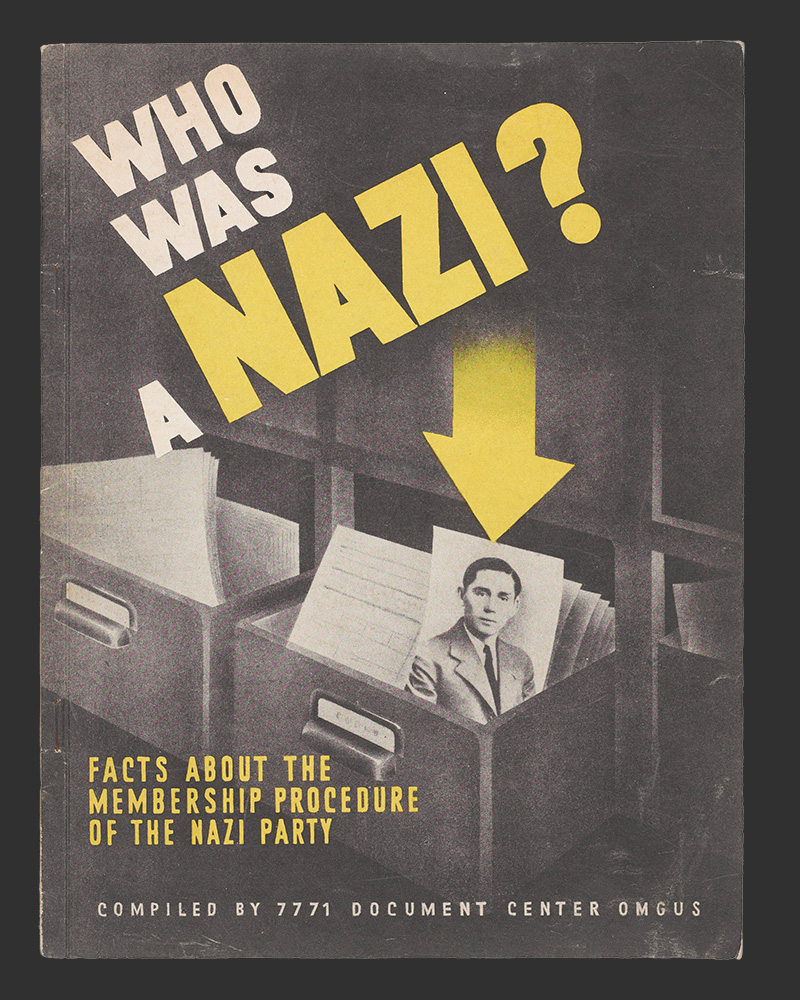

Denazification

In September, the Allied Control Council in Germany passed its first piece of legislation. Control Council Law No 1 repealed Nazi laws as part of denazification.

Ridding the country of Nazism was a complex process, with challenging decisions over who ought to face justice. The pamphlet above was published to help British and American soldiers during their investigations.

Image courtesy of IWM

Belsen Trial Begins

On 17 September, the first war crimes trial began in Lüneburg, Germany. The Belsen trial was held under a Royal Warrant and took the form of a court martial, with British Army soldiers as judges.

This was the first time that anybody accused of war crimes in Nazi Germany faced justice. The defendants included Josef Kramer (pictured), the former commandant of Auschwitz-Birkenau and Bergen-Belsen camps.

Prime Minister Attlee promises Indian independence

On 19 September, Britain’s prime minister Clement Attlee made a worldwide broadcast promising independence for India ‘at the earliest possible date’.

It was a monumental decision that would have huge implications for the future of India, Britain and the British Army.

Hamburg, a city of rubble

By the late summer of 1945, British commanders in Germany held an increasingly pessimistic outlook. Much of the British zone lay in ruins.

In Hamburg (pictured), 50 per cent of all housing, 90 per cent of all schools and 40 per cent of hospitals were destroyed. Most towns and cities under British control were in a similar state.

Any attempt to ‘win the peace’ and implement the grand plans laid out at Potsdam would first require the restoration of the basic necessities of civilian life. Yet the means to achieve this were far from clear.

North-West German Broadcasting

As part of the re-education efforts in Germany, British Army authorities in Hamburg helped set up Nordwestdeutscher Rundfunk (NWDR) as the radio station for the British zone.

On 22 September, NWDR aired its first radio broadcast. The station was modelled on the BBC, complete with a charter. A former head of the BBC German Service, Hugh Carleton Greene, was its first director-general. It proved immensely popular among the local German population.

Black market in Germany

In postwar Germany, use of the black market was incredibly widespread among civilians and Allied troops alike. It was hugely detrimental to the struggling German economy – although for most Germans it was the only way to acquire many essentials, including sufficient food rations.

For British and Allied troops, the black market was more of a luxury. It offered a means to make money, obtain gifts and supplement already generous alcohol rations.

Within a year, the occupation authorities felt obliged to produce their own money to help curtail this illicit trading. British Armed Forces Special Vouchers (pictured) became the only valid tender for British personnel in official premises.

‘It was not long before the Allied soldier realized the vast purchasing and persuasive power he had in his possession of cigarettes... He saw that he could make money on which to have a good time, that he could not only keep his pay intact but could also acquire fountain pens, cinematograph apparatus, jewels, watches, antiques, diamonds and binoculars.’Extract from Lieutenant-Colonel Wilfred Byford-Jones’s memoir 'Berlin Twilight' — 1947

The food crisis

For the people of Europe - victors and vanquished, victims and perpetrators - hunger of varying degrees was a fact of life. These problems were felt most keenly in Germany, where the destruction was most pervasive.

The Allied occupiers were an exception to this near-universal rule. With their Navy, Army and Air Force Institutes (NAAFI) clubs and mess halls, British soldiers and civilian administrators were able to access a fantastic array of rations.

This contrasted not only with the local conditions, but even the experiences of friends and family back in Britain, where food remained relatively scarce.

‘The dinner by pre-war standards was not excessive. It was the normal pre-war guest night five courses, but each course was very good and ample, and the consequence was that I lay awake long while steam rollers rumbled around the guts. It is really shameful to be writing of such goings on in a world of dearth, and I take it that the nuit blanche [sleepless night] was only my deserts.’Letter from Lieutenant Colonel Harold Newman, British Army of the Rhine, to his wife — 23 September 1945

Non-contact rules fully relaxed

On 25 September, British authorities brought an end to the strict non-fraternisation rules between the occupiers and the occupied in Germany.

While regulations around British soldiers billeting in German households remained in place, all other restrictions were lifted.

Between 1947 and 1950, an estimated 10,000 British–German couples married, despite widespread prejudice.

Back in the saddle

The lifting of non-fraternisation rules meant that German civilians were now also able to spectate at British Army events – whether it be football matches or equestrian competitions.

Pictured above is Lieutenant William Stanhope, of the 15th/19th The King's Royal Hussars, competing at a regimental gymkhana near the town of Kappeln.

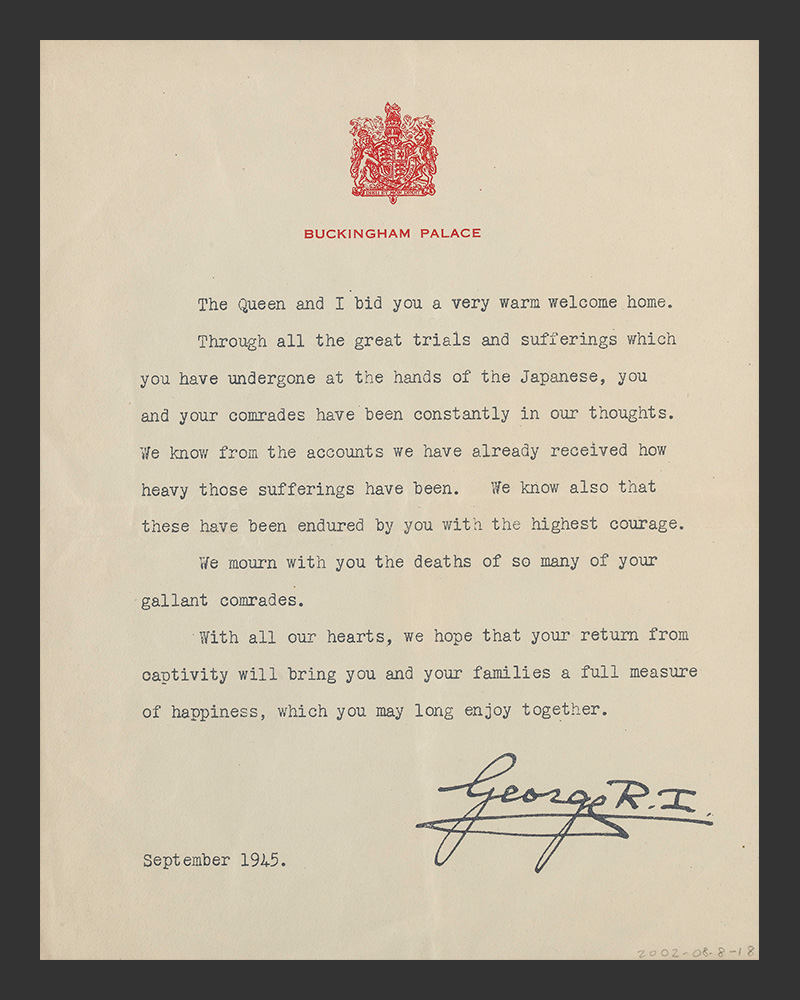

Welcome Home

In September 1945, King George VI sent this personal message to former prisoners of war returning home from Japanese camps in Asia.

‘It is quite hopeless at a time like this to try to give you any sort of idea of what I have been doing all these years… Like everybody else, I have been keeping my emotions locked up and simply not using them, and now when I am suddenly able to let go a bit I hardly know where or how to start. But for me you are still everything in the world, and everything I understand in the way of freedom, and happiness and fun.’Major Alan Glendinning's first letter home to his wife after several years in a Japanese POW camp

Trouble in Palestine escalates

During the 1945 general election campaign, the Labour Party had pledged to lift restrictions on Jewish immigration to the British mandate of Palestine, which had a majority-Arab population. However, once in power, the new foreign secretary Ernest Bevin was anxious not to inflame Arab opinion in the region and opted not to remove the immigration limits.

In Palestine, tensions heightened as armed Jewish resistance groups, with a shared goal of establishing a national homeland, now united in opposition to British forces and the Palestine Police. (A member of the mounted branch of the Palestine Police Force is pictured above).

After a series of Zionist paramilitary attacks, Britain declared a state of emergency in Palestine on 27 September.

‘At my request, I was taken to a Mosque near the Depot by Capt. Nur Asaf, a [Muslim] Officer who is my adjutant... The general appearance of the building was not very dissimilar to that of a London city church, with forecourt, surrounded by buildings, though in the forecourt were two minarets (which I can see from my bed) whence the faithful may be summoned to prayer.’Major Oliver Wright Holmes, Royal Army Ordnance Corps, documenting his time in Rangoon (now Yangon), Burma — 30 September 1945

On This Day: 1945

This is the ninth instalment of a series exploring the British Army's role in 1945 – one of the most decisive years in modern history – drawing upon the National Army Museum's vast collection of objects, photographs and personal testimonies.

Throughout 2025, a new instalment will be released each month that focuses on events from 80 years beforehand. The series will highlight the everyday experiences of Britain’s soldiers alongside events of grand historical significance.