An Irish gentleman

Born in 1700, Philip Townsend was an Irishman of Anglo-Protestant descent. His grandfather, Colonel Richard Townsend, had been a prominent Parliamentarian officer during the British Civil Wars (1642-51).

In 1726, Philip inherited his father’s estate of Derry House in Rosscarbery, County Cork. Seven years later, he married Elizabeth Hungerford, the daughter of a fellow member of the Cork gentry. The couple were to enjoy a long and happy life together.

Surviving letters addressed to his ‘dearest dear Bess’ reveal the deep affection that Townsend felt for his wife. Extracts of these letter were published in ‘An Officer of the Long Parliament’ (1892), a book which chronicles the life of Richard Townsend and his descendants.

Detail from 'A New and Correct Map of the County of Cork' (1750), showing the location of Derry House and the Hungerford family's estate on Inchydoney Island (Source: gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France)

A mature volunteer

In April 1756, well into middle age, Townsend chose to join the Army, obtaining a commission in General Richard O’Farrell’s 22nd Regiment of Foot.

It's curious that a married man with six children would take up a military position so late in life. It's possible that he was compelled by debt. Or perhaps it reflected a desire to uphold his family’s tradition of military service. He may simply have had a hankering to go on a grand adventure before he grew too old.

Whatever the reason, in November 1756, he sailed with his regiment to North America, accompanied by his youngest son, Tom, who had also volunteered. Here, he was to take part in a struggle for continental supremacy between Britain and France, a campaign which formed part of a sprawling global conflict known to history as the Seven Years War (1756-63).

Atlantic crossing

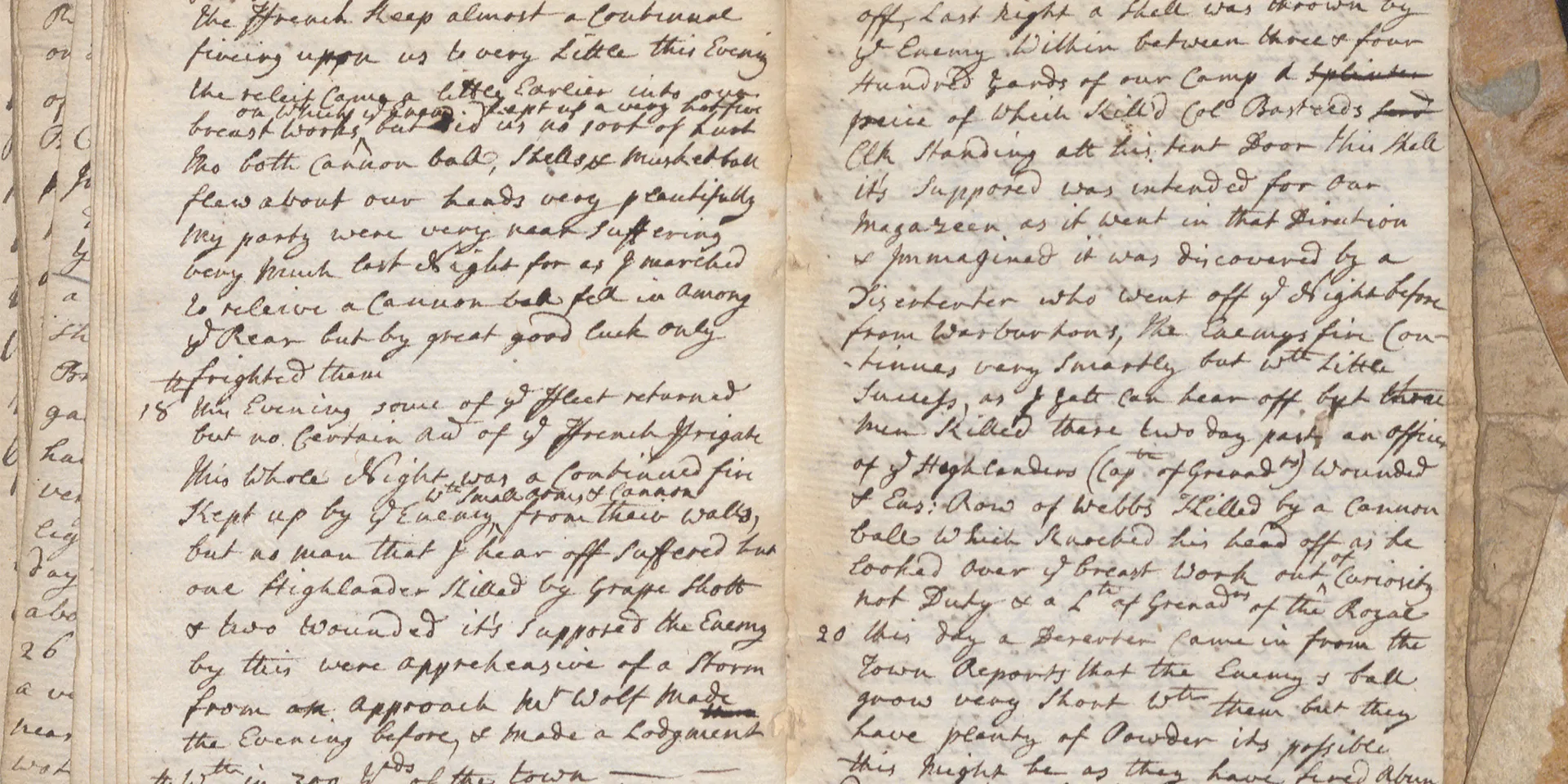

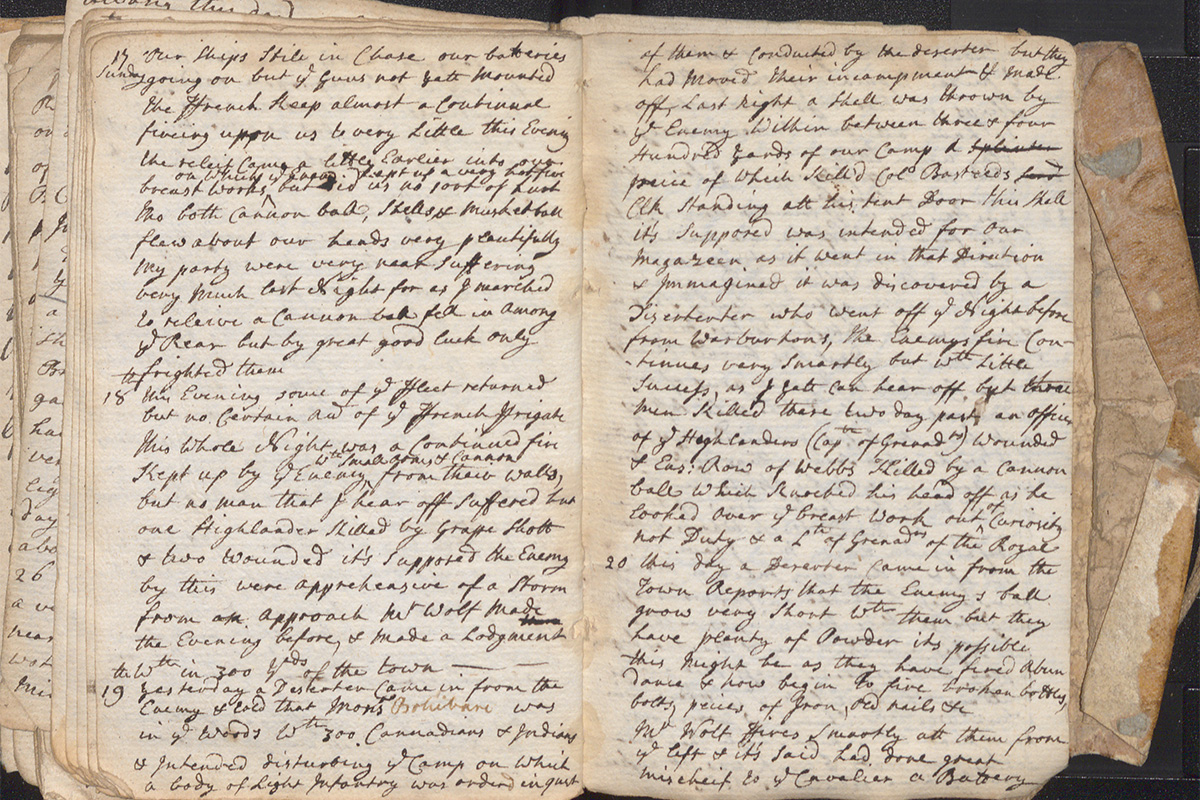

As he embarked on his journey, Townsend began a diary, which he kept up for the next 18 months of his service. He doesn't mention his motivation, but it seems likely that he wished to make a private record of what would surely be the most eventful episode in his life.

Atlantic crossings in the 18th century were long, arduous and fraught with danger. The 14-week voyage certainly took its toll on Townsend. His diary entries during this period are scant, a consequence not only of the monotony of the journey, but also of the terrible bouts of seasickness to which he succumbed for many weeks.

Travel writing

Townsend arrived in New York on 9 February 1757. He then travelled up the Hudson River to Albany, the front line of the war with the French.

His diary during this period has something of the feel of a travelogue, in which he captures his impressions of the country and its people. The splendour of the landscape especially caught his eye. He remarked of the Hudson that it is ‘a most beautiful river as one’s imagination can form without art to beautify it’.

Frontier warfare

These pleasant reflections stood in contrast to the harsh nature of the war in this isolated region. Here, the French with their indigenous American allies mounted raids upon the settlers of British frontier territory.

Townsend recorded several brutal acts of war perpetrated by the enemy. These included an attack on a village in which 12 people were killed, 100 taken prisoner and 40 dwellings destroyed. On another occasion, he saw a raiding party attack a house near the fort where he was stationed. The inhabitants were slaughtered and the property was burned to the ground.

The bitter winter conditions prevented the British from coming to their aid. Townsend lamented in his diary: ‘We had no snow shoes and the snow was at least three feet deep.’

In a letter to his wife, he blamed the barbarity of these attacks on the French, writing: ‘By all accounts, the Indians [sic] never used such cruelty until instructed by them [i.e. the French].’ He also noted how these actions filled the men with resentment and a keen desire to exact revenge.

‘The enemy about three in the afternoon burned a house & barn opposite the fort and took from thence four youths & a girl, the man of the house being on this side of the river and had a melancholy prospect of his house and barn in flames, the youths & girl were miserably butchered some little distance from the house & scalped.’Townsend describing a brutal attack on a family dwelling — 19 February 1757

Louisbourg

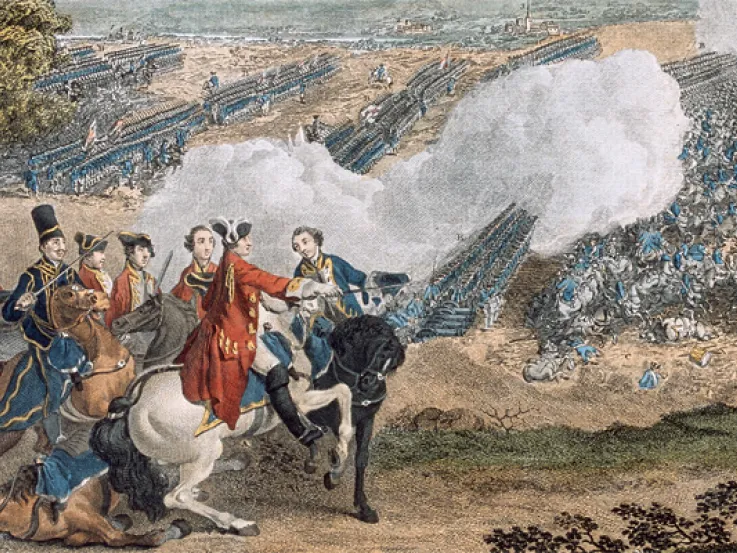

The opportunity for vengeance came in June 1758, when the 22nd Foot took part in the assault on the Fortress of Louisbourg on Île Royale (present-day Cape Breton Island, in the Canadian province of Nova Scotia).

Guarding the entrance to the Gulf of St Lawrence, and access to the St Lawrence River, Louisbourg was a vital strategic objective for the British. Its capture was a prerequisite for an invasion of Quebec, the heartland of French colonial possessions in North America.

The British used their naval supremacy to blockade the port, before launching an amphibious assault to capture the surrounding territory. They then laid siege lines, deployed their gun batteries, and proceeded to bombard the fortress, eventually forcing its surrender on 26 July.

Campaign narrative

Townsend was clearly conscious of the historical significance of the attack on Louisbourg. It forms the most detailed section of his diary.

His account includes many remarkable incidents of destructive fire, casualties and close shaves. It is also notable for a brief appraisal of Brigadier General James Wolfe, who would go on to die at the moment of victory over the French at the Battle of Quebec (1759), becoming a national hero.

However, this part of the diary is also the most impersonal. It has the character of a campaign history and Townsend makes only fleeting reference to himself and his unit. This detached style has a major drawback, failing to offer a deeper understanding of what it was like to experience war first-hand during this period.

‘My party were very near suffering very much last night for, as I marched to relieve, a cannonball fell in among the rear but by great good luck only frighted them.’Philip Townsend, diary entry — 17 July 1758

‘The most indefatigable active man I have heard of & to him very much is owing our success hitherto and forwardness in the siege.’Townsend on Brigadier General James Wolfe — 22 July 1758

Returning home

Despite this change in writing style, some insight into the personal toll that the campaign took on Townsend can be found near the end of the diary, where he notes (on 23 July) that he was excused from duty on account of cold and fatigue.

He elaborated upon his condition in a letter to his wife later that year, describing how he had been taken ill for nearly three weeks and had ‘such a tremor that I could scarce write’.

He was granted permission to sell his commission on the grounds of ill-health, believing the sum he would obtain would be sufficient to clear any debts. Tom, his son, continued in service and fought under Wolfe at Quebec.

Townsend eventually returned home to Ireland. Reunited with his family, he lived for many more years, dying at the ripe old age of 86.

Access to the Archive

The National Army Museum provides public access to its library and archival collections via the Templer Study Centre. Over the coming weeks and months, we will be sharing more stories across our website and social media channels, highlighting some of the valuable personal insights these collections hold.