Victory in Europe

When 8 May 1945 was declared Victory in Europe Day (VE Day), British soldiers and civilians were finally able to celebrate the defeat of Nazi Germany after six long years of war.

Across the world, crowds flocked to greet the good news. From conga lines on London's Trafalgar Square to a grand victory parade through the streets of the Kenyan capital, Nairobi, there was no shortage of revelry.

Yet for some, the news prompted a more sober response. Whether remembering lost loved ones or contemplating the uncertain prospect of what was to come next, VE Day was also a time for reflection.

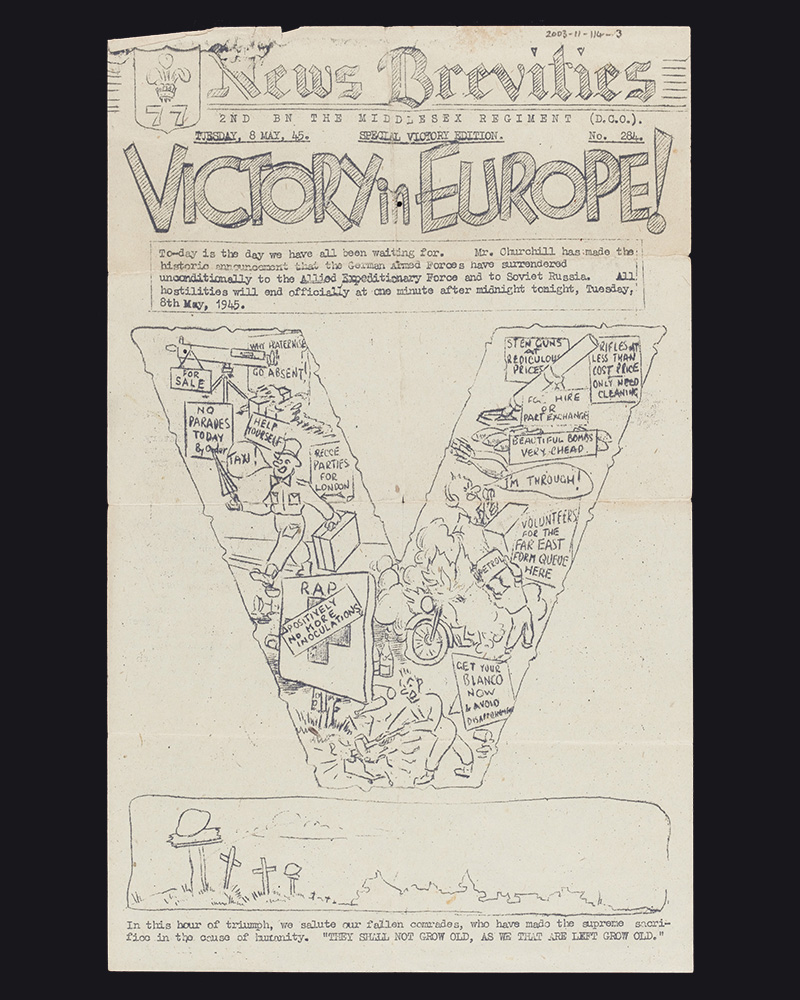

Special victory edition of 'News Brevitas', the newsletter of 2nd Battalion, The Middlesex Regiment, 8 May 1945

VE Day edition of ‘Union Jack’, the British Forces daily newspaper, issued in Northern Italy, 8 May 1945

Meanwhile, British and Indian soldiers in Burma (now Myanmar) continued to encounter fierce Japanese resistance. Faced with the additional challenge of monsoon weather conditions, their advance had slowed significantly.

The capture of the capital Rangoon (now Yangon) in early May allowed many soldiers in the region to celebrate their own hard-fought victory. However, the defeat of Japanese forces in Burma did not mark an end to the conflict. Plans were under way for an invasion of Japan's home islands in the months to come.

‘We have won the German war. Let us now win the peace.’Field Marshal Montgomery’s victory speech to soldiers of the 21st Army, Germany — 8 May 1945

Winning the peace

With the war in Europe at an end, soldiers of the British Army now confronted the complex challenges of the peace. In Germany, a combined force of British soldiers and civilians ran a military government alongside their French, American and Soviet counterparts.

For the hundreds of thousands of British soldiers stationed across north-west Germany, the task ahead was daunting. Almost every large town and city was in ruins after years of Allied bombing, basic utilities were generally unavailable, and millions of civilians lived among the rubble in desperate need of food.

For the first weeks after VE Day, British and Allied soldiers fought desperately against the total breakdown of German society as they attempted to establish their own authority as occupiers.

The British delegation to Potsdam visits the ruins of the Reichstag in Berlin, 16 July 1945

Elsewhere in Europe, the British Army took part in the various ‘Control Commissions’ set up to administer former Axis nations, including in Italy and Romania. In every case, the prevailing conditions were different: the tasks given to Britain’s soldiers ranged from diplomacy to firefighting.

There were cross-continental challenges too, not least of which were the millions of ‘Displaced Persons’ left stranded across Europe and desperately seeking a route home. These refugees included former forced labourers and Holocaust survivors. The British Army and its allies were also responsible for pursuing justice against suspected perpetrators of the Holocaust in Germany and beyond.

It was only at Potsdam (17 July – 2 August 1945) that the ‘Big Three’ – the United Kingdom, the United States and the Soviet Union – agreed upon a final plan for ‘winning the peace’ in Europe. Most importantly, the Allies established the main objectives of the occupation of Germany, best summarised as the ‘Four Ds’: Denazification, Demilitarisation, De-industrialisation and Democratisation.

In addition, large swathes of German territory would now become part of Poland, requiring a major westward population transfer of the existing German inhabitants of this region. Other outstanding territorial and political disputes were expected to be resolved in the years ahead.

The Potsdam Conference

We'll meet again

It was clear in the summer of 1945 that the British Army’s work was far from done, whether it was the pursuit of a final victory against Japan or the complex challenges of ‘winning the peace’ in Europe.

There was, at least, no shortage of personnel. In June 1945, the Army reached its wartime peak of 3.1 million serving soldiers, with expertise ranging from warfighting to civil engineering.

But what did the future hold? The overwhelming majority of Britain’s soldiers were conscripts, now eagerly anticipating their return to ‘civvy street’. Yet their path home was anything but straightforward.

After the First World War (1914-18), a chaotic demobilisation process had brought about mass unemployment and contributed to a major economic depression in Britain. In 1945, the British government attempted to implement a much more methodical, systematic approach.

Many British soldiers would be waiting for months, even years, before their number (representing a combination of age and service length) was called. There were some fast-tracked exceptions, including those deemed vital to postwar reconstruction. Likewise, liberated British prisoners of war in Europe were now urgently returned home after years of imprisonment.

For everyone, whether facing the prospect of a possible transfer to the Far East or looking forward to a reunion with loved ones back in Britain, there was hope for a fresh start once the war was over.

In July 1945, the UK held its first general election for a decade. The unexpected landslide for the Labour Party’s socialist programme of radical reform was, in part, a consequence of the common demand among soldiers and civilians alike for some recognition of their sacrifices during a time of national emergency.

‘[Demobilisation is] a problem the solution of which will determine the happiness, contentment and future prosperity of this country of ours for many years to come.’Ernest Bevin, Minister of Labour, London — 12 May 1945

The end is just the beginning

In mid-July, the world changed forever. The successful detonation of a nuclear bomb marked the beginning of the atomic age. This weapon of overwhelming destructive force would radically reshape warfare in the decades to come.

In early August, the United States opted to use their new superweapon on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The unprecedented devastation that resulted, and the threat of further nuclear attacks, quickly prompted Japan’s total and unconditional surrender on 15 August.

Victory over Japan signalled the end of the Second World War, giving rise to further celebrations across Britain and the world. The defeat of Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy and Imperial Japan was a momentous achievement that had required huge sacrifices. Millions had lost their lives, cities and towns lay in ruins, and many of the survivors – both military and civilian – held on to the trauma of their experiences.

With the fighting finally over, attention now turned to the important work of reconstruction and the pursuit of a lasting peace in the East. The surrender of Japanese forces quickly instigated local power struggles across South-east Asia, as national independence movements staked a claim to control their own destiny rather than returning to European colonial rule.

British and Indian soldiers were soon tasked with reasserting control over Britain’s imperial holdings, including Hong Kong and Singapore. Around the same time, they also became entangled in armed conflict with anti-colonial movements in both Vietnam and Indonesia.

Across the globe, it was clear that the end of the Second World War marked the beginning of a whole new conflict over the future. In some places, this was primarily a question of diplomacy and ideology; in others, open warfare broke out between opposing factions.

On all fronts, British and Empire soldiers would be actively involved as occupiers, diplomats, imperial governors, peacekeepers, and much more besides.

‘Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.’J Robert Oppenheimer – the director of the Manhattan Project’s atomic bomb development programme – quoting the Bhagavad Gita upon witnessing the first ever nuclear explosion — 16 July 1945

On This Day: 1945

This story sets the scene for the second stage of our series exploring the British Army's role in 1945 - one of the most decisive years in modern history. The series draws upon the National Army Museum's vast collection of objects, photographs and personal testimonies.

Throughout 2025, a new instalment will be released each month that focuses on events from 80 years beforehand. The series will highlight the everyday experiences of Britain’s soldiers alongside events of grand historical significance.