Outbreak

In December 1740, King Frederick II of Prussia invaded the Austrian province of Silesia. This sparked a conflict that eventually saw Prussia ally itself with France, Bavaria, Spain, Sweden and Saxony.

These states all sought to exploit the succession struggle to acquire Habsburg possessions for themselves and diminish Austrian power. Ranged against them were Austria, Britain, the United Provinces and Russia.

Britain’s European war aims were to prevent the French from overrunning the Austrian Netherlands (now Belgium) and to protect its Hanoverian territory (King George II of Britain was also Elector of Hanover).

The British Army’s establishment was rapidly increased, new regiments were raised and in 1742 a force of 16,000 men was sent to Flanders in support of the Austrians.

War against France

In 1742, Austria and Prussia made peace, freeing the former to concentrate its efforts against France.

Lord Stair, the veteran British commander in the Low Countries, recommended a joint attack on the French at Dunkirk, followed by an invasion of France. However, he was overruled and in February 1743 he led his army into Germany.

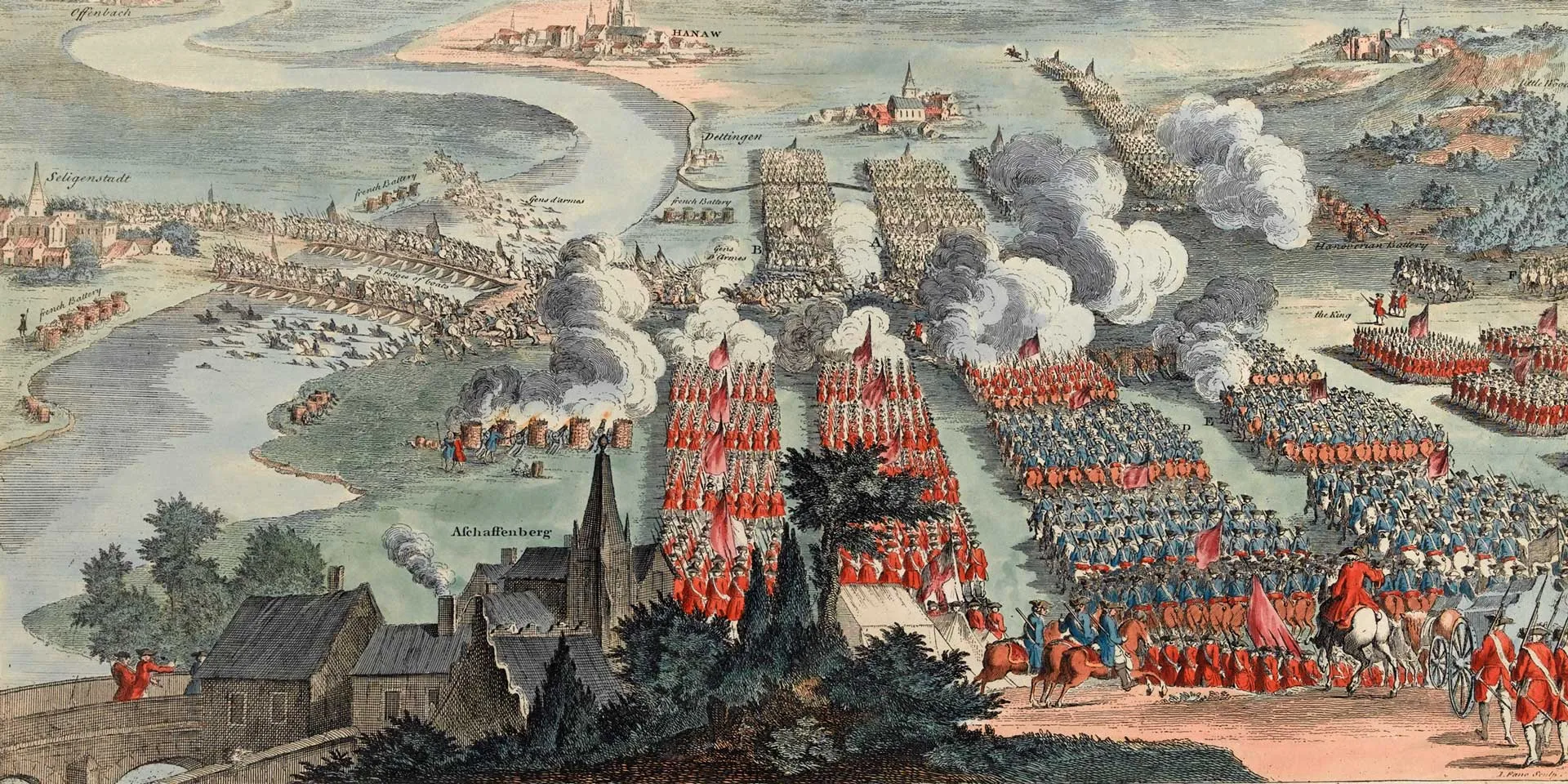

Dettingen

On 19 June, King George II arrived to take over command of the Army. Although his personal bravery was never in question, George was no general and he was soon outmanoeuvred by the French. On 27 June, he found himself near Dettingen in Bavaria, cut off from his base at Hanau and hemmed in between hills and the River Main.

However, when the French attacked, their troops were broken by the steady volleys of the British infantry. Their rout was eventually completed by the British and Austrian cavalry. Although Stair wished to pursue the beaten French, the King decided to make for the safety of Hanau.

The battle had little strategic impact on the war but it demonstrated the fighting qualities of the British Army. Dettingen was also the last time a British monarch led his troops in battle.

Tournai

In 1744, the French succeeded in overrunning much of western Flanders. They resumed their offensive in 1745 and laid siege to the fortress of Tournai.

The British Army was now under the command of the King’s son, the Duke of Cumberland. In May 1745, he marched to relieve Tournai with an army of 47,000 including 23,000 British soldiers.

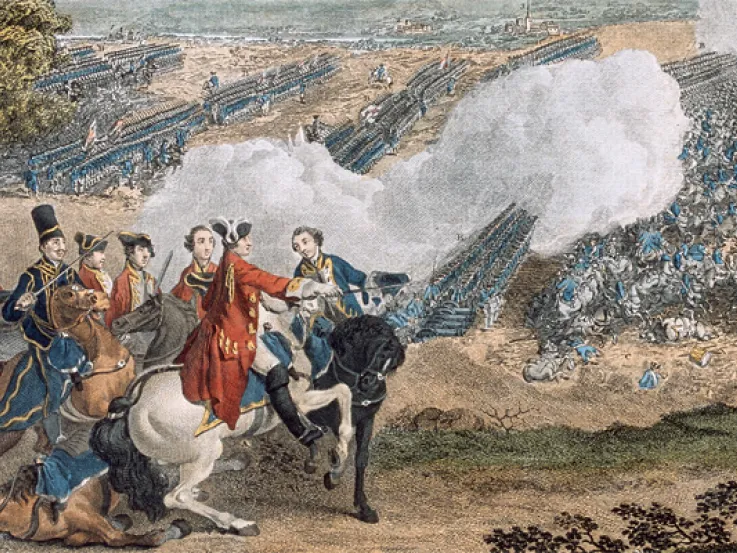

Fontenoy

On 11 May, Cumberland clashed with Marshal Maurice de Saxe’s French Army at Fontenoy. Although the French occupied a strong position defended by formidable redoubts, and had the advantage of numbers, Cumberland decided to attack. The Austrians and the Dutch made little progress, but in the centre the British and Hanoverian infantry broke into the French position.

Saxe, unable to sit on his horse due to dropsy and carried around in a wicker chariot, now counter-attacked with all his available infantry, cavalry and artillery. The British and Hanoverians withstood numerous assaults until, heavily outnumbered and with no support, they were forced to withdraw.

Fontenoy had once again demonstrated the fighting qualities of the British infantry, but it was nonetheless a defeat. Cumberland lost 7,500 men and Tournai surrendered ten days later.

French success

In July 1745, Saxe captured Ghent and its garrison of British and Dutch troops. Bruge, Oudenarde and Ostend soon followed. Shortly afterwards, the bulk of the British Army was withdrawn to deal with the Jacobite Rebellion at home, severely weakening the Allies in Flanders.

Saxe then continued to capture towns in the Austrian Netherlands, culminating with the fall of the capital, Brussels, in February 1746.

Lauffeld

Cumberland returned in 1747. But on 2 July, he was defeated by Saxe at the Battle of Lauffeld, fought near Tongeren and Maastricht. This engagement saw 67-year-old General Jean Louis Ligonier lead a desperate cavalry charge which preserved Cumberland’s beaten army from destruction.

Saxe followed this up with victories at Bergen op Zoom (September 1747) and Maastricht (May 1748).

Colonies

The war also involved colonial conflict, particularly between Britain and France. The French seized the British East India Company’s trading base of Madras, while the British unsuccessfully besieged Pondicherry.

In Canada, a force of British colonists, supported by the Royal Navy, captured the French fortress of Louisbourg.

Peace

By the Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle, signed in October 1748, France agreed to leave the Austrian Netherlands and give back Madras in return for Louisbourg. Maria Theresa was also confirmed as Austrian ruler.

In fact, the Peace turned out to be little more than a truce. Hostilities continued in India and Canada, and would soon break out again between Prussia and Austria.