German withdrawal

Efforts to contain the Allied offensives of 1916 proved costly for the Germans. Their high command therefore decided on a defensive strategy for 1917.

Between February and April, they withdrew to a new fortified position known as the Hindenburg Line. Significantly shorter, and protected with pillboxes and deep belts of wire, it gave the Germans a stronger position to defend.

During their withdrawal, the Germans destroyed buildings, wells and watercourses, roads and railways. This prevented the Allies from fully exploiting the abandoned ground.

Allied plans

Initially, the Allies had planned a joint offensive with the Russians in the Spring. But, following revolution in February 1917, Russia withdrew its commitment to attack on the Eastern Front.

In March, the French instead opted to advance along the River Aisne. France’s new commander-in-chief, General Robert Nivelle, was convinced this would deliver a war-winning breakthrough.

The German withdrawal to the Hindenburg Line temporarily disrupted Nivelle’s plans. But the Allies eventually agreed that the British would launch a diversionary attack at Arras, drawing German troops away from the Aisne and assisting the French attack.

Arras

The Battle of Arras began with a barrage on 4 April 1917. The Allies had learnt valuable lessons from their mistakes on the Somme. Specialised artillery units targeted German guns through counter-battery fire. By adopting new methods like sound ranging and flash spotting, they neutralised enemy batteries before the attack.

The British were aware that they could not wipe out the Germans with shells. But their extended bombardment exhausted and demoralised enemy troops by pinning them down inside their dugouts without access to rations or supplies.

Early success

The British guns fell silent on 8 April. At 5.25am the following morning, after a delay to confuse the enemy, they resumed their fire in a hurricane five-minute bombardment. The troops then advanced.

The weather proved an unlikely ally. A sudden squall of heavy snowfall blew towards the German lines, allowing many of the attackers to reach their goals in poor visibilty.

Good progress was made, with elements of the First, Third and Fifth Armies advancing up to 8km (5 miles) in the first two days. The attack also achieved its objective of drawing German troops away from the Aisne in advance of the French assault.

‘At 5.30am the Canadians went over the top in front of Vimy Ridge, preceded by an intense barrage from our field guns, and also a liquid fire attack, the most wonderful sight you can possibly imagine… At 7.34am we went over behind our barrage followed by four tanks. By the time we reached the summit of the ridge there was not an ounce of wind left in any of the men and we were rather disorganised. On coming within sight of the Bosche we were met by machine gun and rifle fire. At one moment things looked rather black, as we came up to our barrage too soon and were compelled to halt for a couple of minutes, during which time we took cover as best we could in shell holes until the barrage lifted, but we managed to reach our objective, where the Bosche were ready to give themselves up… The trenches were wiped out of existence, and not a trace of wire, which bears testimony to the marvellous shooting of the artillery. They came streaming out of their dugouts by the hundreds, miserable wretches having been down there without food for days.’Letter from Second Lieutenant Robert Fitzgerald, The Oxford and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry — 21 May 1917

Attack slows

But the early progress was eventually halted by tough German resistance and logistics problems. Reinforcements, artillery and supplies could not keep up with the advancing troops. By 16 May - the official end of the battle - the Arras front had returned to the stalemate of trench warfare.

‘We had advanced so far and so quickly that our infantry outposts were now beyond the extreme range of their own field guns, so that we waited expectantly for our cavalry to come up and exploit the complete break in the German defensive system. But they did not come… That night our outlying patrols were actually withdrawn, in spite of protests, so that they could be covered by our guns, and the positions we gave up that evening we later had to fight four months to regain.’Lieutenant Richard Talbot Kelly, Royal Artillery — 1917

Heavy losses

Casualties surpassed 150,000 for the British and Canadians, and 100,000 for the Germans. Once again, there had been no breakthrough, although the Canadian Corps gained some success in taking Vimy Ridge, a key feature that dominated the surrounding area.

Several days later, the French offensive on the Aisne also ground to a halt after massive casualties. This latest failure led to mutinies in the French Army and Nivelle’s dismissal.

Still, the Arras operation showed that the British had learned lessons from the Somme. They were developing new methods for set-piece attacks against German defences, including infantry-tank co-operation and close air support.

Messines

The British began another assault on 7 June 1917, with a series of huge mine explosions at Messines Ridge. They killed around 10,000 Germans and totally disrupted their lines.

Following the detonation of the mines, nine Allied infantry divisions attacked under a creeping artillery barrage, supported by 72 Mark IV tanks.

They gained their initial objectives due to the devastating effect of the mines. They were also helped by the German reserves being positioned too far back to intervene.

German counter-attacks continued until 14 June. But, by then, the entire Messines salient was in Allied hands.

New offensive

Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig intended to use the captured ridge and salient as a launch point for another offensive. This operation was designed to drive a hole in the enemy lines, advance to the Belgian coast and capture the ports, thus removing the German submarine threat to the British war effort.

An attack would also take the pressure off the French. Their army had experienced a series of mutinies following the disastrous Nivelle offensive and needed to recuperate.

Fatal delay

Unfortunately, Haig was persuaded to delay this new assault. General Herbert Plummer, the Second Army commander, believed the ridge first had to be consolidated. At the same time, Haig’s political superiors were reluctant to provide him with new troops for the offensive.

By the time Haig received the extra men he needed, the time for exploiting the breakthrough was long past. The Germans knew the offensive was coming and moved more troops in to bolster their defences.

They also constructed a formidable system of pillboxes made from reinforced concrete. These protected front-line troops from the Allied bombardment and were positioned to provide mutually supporting fire.

Passchendaele

Despite these drawbacks, the Third Battle of Ypres (or Passchendaele) was launched on 31 July 1917 after a two-week preliminary bombardment that failed to destroy the heavily fortified German positions. The initial Anglo-French attack (the Battle of Pilckem Ridge) was hampered by heavy rain and failed to achieve a breakthrough. But the Allies captured a substantial amount of ground from which they hoped to renew their assault.

The subsequent Battle of Langemarck (16-18 August) saw two days of fierce fighting in muddy conditions. This again resulted in small gains and heavy casualties for the British.

‘In the evening a small party of us went forward to locate possible gun positions... It was almost impossible to walk with any degree of safety. It was just a question of keeping to the lips of the shell holes. These, in most cases, had merged into wide extended holes already filling with water. Ahead, as far as I could see, conditions were the same, some of these water-filled depressions resembled small lakes, the result of clusters of shells falling in a limited area. 'The conditions finally brought us to a halt. There was no way vehicle or packhorse traffic could move. These conditions prevented sufficient supplies being brought forward quickly enough. Movement on any scale was too hazardous. Guns could not be brought to this location. The conditions provided the Germans with near perfect defensive cover. The land drainage system of the surrounding country had been destroyed.’Diary of Bombardier William Weyman, Royal Field Artillery — 8 August 1917

Bogged down

The foul weather and waterlogged terrain forced the British to halt the offensive temporarily in the hope that the ground would dry out. When it resumed, strong German resistance, including the use of mustard gas, saw the operation grind to a halt in the shell-churned mud.

Cost

By the time the Canadians had captured the town of Passchendaele on 6 November 1917, the British had advanced 8km (5 miles). Commonwealth and French losses approached 300,000. German casualties were 260,000.

This battle of attrition almost broke the resolve of both armies. The Germans, with fewer men, could less afford the casualties than the Allies. Nevertheless, Field Marshal Haig and the high command have since been accused of continuing the offensive long after it was clear to many that men were dying for relatively little strategic gain.

Cambrai

While the struggle at Passchendaele dragged on, the British high command approved a plan to attack and encircle the German-held town of Cambrai, an important railhead. It was defended by the formidable Hindenburg Line. The operation would be an 'all arms' battle, using tanks, cavalry, aircraft, artillery and infantry.

Surprise attack

On 20 November 1917, the Germans were surprised by a brief but intense artillery attack on a 10-mile front. Soon after, more than 400 British tanks advanced across the ground, supported by infantry.

A creeping artillery barrage assisted their assault and 14 Royal Flying Corps squadrons attacked trenches, supply convoys, artillery emplacements and other front-line installations.

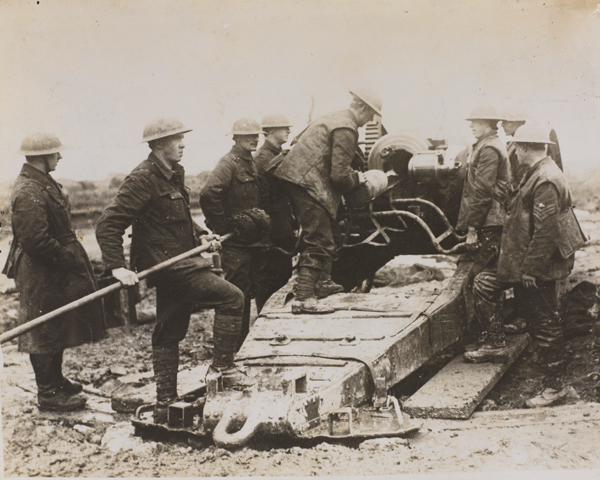

Tanks

Many tanks were fitted with huge bundles of sticks, known as fascines, to be tipped into the deep ditches of the enemy lines. These would form bridges over which the following tanks and infantry could crawl.

The initial attack went well, with some units advancing more than 5 miles from their starting points. Thousands of enemy prisoners were taken and all three lines of the Hindenburg defences were penetrated.

‘The tanks started and we all got up and on the move… We had formed up in artillery formation and we came to the gap in the wire, each section and platoon ran through the gap and took up the same formation the other side. This manoeuvre we had practiced over and over again… and everything seemed to be going well… Suddenly there was a tremendous row and I saw a huge red curtain of flame opposite – the barrage had come down on the German line. It was a marvellous site, all along the line red flame spurted in all directions and the noise was appalling. Soon the enemy began to send over a few shells in response... A few men had been hit, these we bandaged up and sent back to the dressing station. We got the men to dig themselves into the bank for by now the enemy had more or less got over the surprise and their machine guns were beginning to be effective; bullets were whistling above our heads… Many aeroplanes were going to and fro, some to fire on the retreating enemy, some to keep in communication with the artillery and some to let HQ know how the battle was going... It was extraordinary watching the tanks go forward followed by the infantry. The enemy shelled them heavily and we saw men falling everywhere and stretcher-bearers rushing up to look after them… Several tanks were knocked out and the infantry were unable to get very far.’Diary of Second Lieutenant Douglas McMurtrie, The Somerset Light Infantry — 20 November 1917

No breakthrough

But the success was short lived. Many tanks broke down or were destroyed by German artillery. Adequate reserves had not been allocated for any major breakthrough.

Indeed, the huge numbers of men stationed at Passchendaele meant there were insufficient troops available. Units also became isolated and there were communication difficulties amid the intense fighting.

Counter-attack

British progress slowed. On 30 November, the Germans launched a major counter-attack, using intensive artillery fire, mortars, gas attacks and infiltrating ‘storm troops’. These advanced deep into the British lines, causing panic in some areas and threatening to cut off several divisions in a trap.

After a period of bitter fighting, the British retreated, keeping only some of the gains they had made at the start of the operation.

The German assault eventually ran out of steam. They suffered similar difficulties to those faced by the British at the start of the battle, such as problems getting reinforcements and supplies forward and battlefield communications and command breaking down.

Overall, British casualties amounted to 44,000 killed, wounded or captured. The Germans sustained around 45,000 casualties.

Lessons

Cambrai demonstrated that the British could break deeply and quickly into the German defences with relatively few casualties. But it also showed that better communication was needed if reinforcements were to exploit the success.

This first massed deployment of tanks and aeroplanes, along with the ferocity and speed of the German counter-stroke, indicated the potential for a new form of offensive operation. It was a lesson that both sides sought to implement in the campaigns of 1918.