Portrait of George Fulton (Frontispiece from the Biographical Memoirs of the late Captain GWW Fulton, 1913)

Early life

George William Wright Fulton was born in the town of Fatehgarh (in modern-day Uttar Pradesh, India) on 23 November 1825.

His father, Major George Bell Fulton - who hailed from Lisburn, County Antrim - enjoyed a distinguished career in the Bengal Artillery. But his service was cut short by his death in 1836, at the age of 47.

Two years later, the family returned to England, where young George completed his schooling at Mount Radford School in Exeter.

A family trade

Fulton followed in his father's military footsteps, joining the Bengal Army. He opted to specialise in engineering rather than artillery, and undertook training at Addiscombe Military College and the Royal Engineers Establishment, Chatham, before returning to India in 1843.

He would soon be joined by his brother, John, who enlisted with the Bengal Artillery, rising to the rank of lieutenant general.

Bad blood

Fulton married Sophia Isabella Wroughton at Allyghur (now Aligarh) on 15 February 1848. A letter published with his journal in 1913 reveals that their marriage was a happy one. The couple went on to have six children.

The letter also shows how Fulton’s service in India was blighted by a bitter conflict with his superior officer, a man he condemned as ‘the most unprincipled, insidious villain that ever lived’.

The feud raged on for several years and would ultimately result in Fulton being expelled from his posting at Jullander (now Jalandhar) in the Punjab region.

A new posting

Fulton's next posting was in Lucknow, a city (in modern-day Uttar Pradesh) renowned for its beauty. This was to prove a much happier chapter in his professional life. He got on well with his new commanding officer, Major John Anderson, and was able to advance his career by securing a promotion to the rank of captain.

Mutiny and rebellion

But this brighter spell was not to last. British rule in India was under growing threat, both from its own Indian troops and the wider populace. Following unrest in Berhampore and Barrackpore, a mutiny among the sepoys of the Bengal Army broke out at Meerut on 10 May 1857. This soon became a full-scale rebellion, which saw a large swathe of northern India engulfed in violence.

Lucknow under threat

Lucknow was the capital of Oudh, a region that had been annexed by the British in 1856. This act of conquest was one of the main causes of the rebellion, and Lucknow was to be a focal point of the fighting and the scene of an epic siege.

The uprising here began on 30 May, when the sepoys stationed outside the city mutinied. While this was immediately suppressed, the spirit of rebellion swiftly spread across the region. Soon, a much larger force of rebels had gathered to threaten the city.

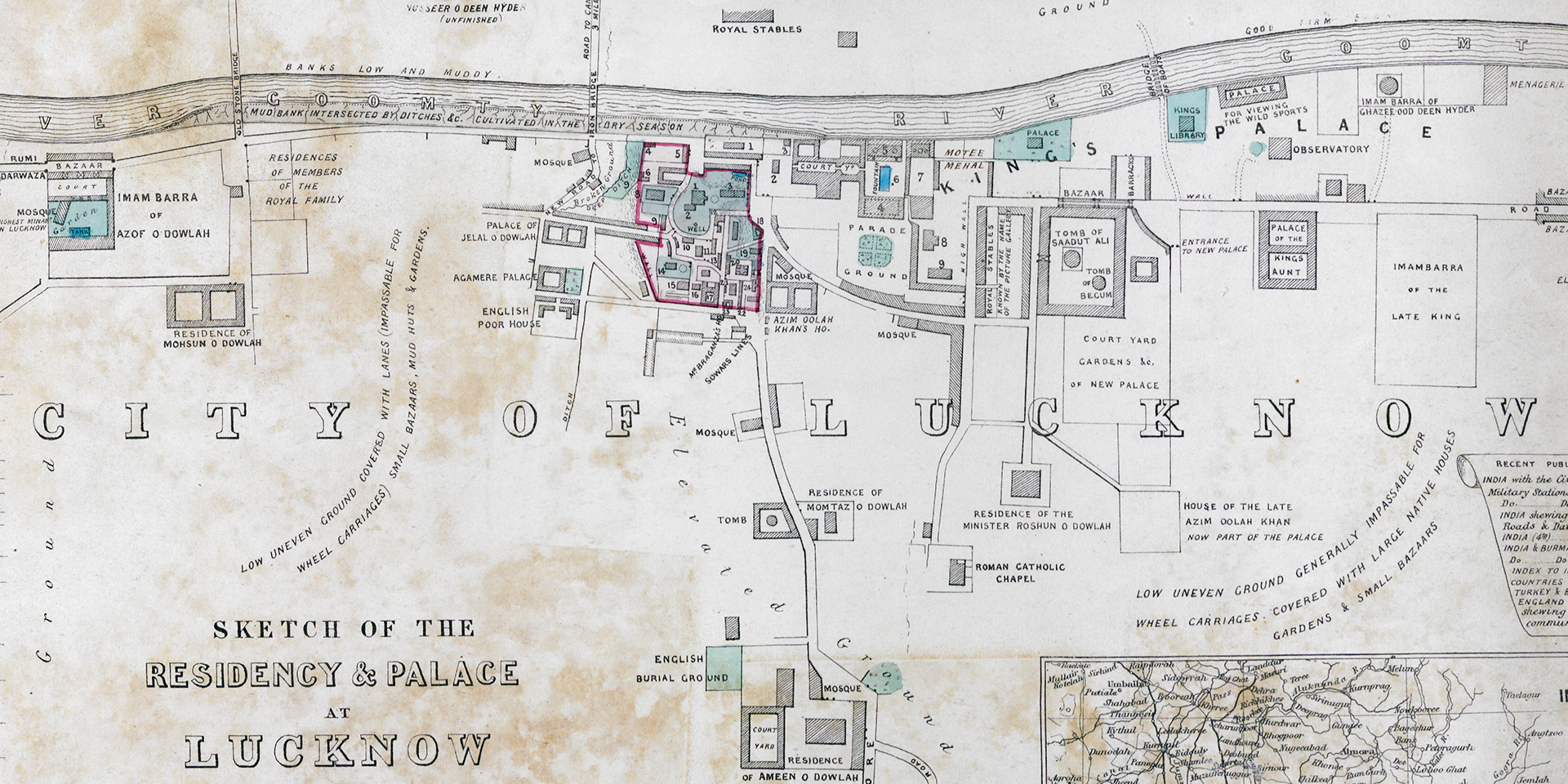

The Residency

With a lengthy siege now in prospect, British civilians and soldiers, together with the Indian troops who had remained loyal, withdrew into the government buildings known as the Residency. Situated in the heart of Lucknow, this was a sprawling complex spanning 30 acres (around 121,000 square metres, or roughly 10 times the size of Trafalgar Square).

The Residency was not designed for a military purpose and its defence presented a serious challenge. Most problematic was its proximity to buildings in the surrounding city which could provide cover for any besieging force or positions for hostile snipers and artillery.

Preparations

The British commander at Lucknow was Brigadier General Sir Henry Lawrence, Chief Commissioner of Oudh. He began laying in provisions of food and ammunition in good time. But he was slow to authorise the construction of defensive works and reluctant to destroy some of the valuable and ornate buildings in the vicinity.

Fulton’s task

The challenging task of preparing the Residency’s defences fell to Fulton. In his diary, he recalled having to beg for permission to begin. But, when finally authorised, he worked furiously to demolish buildings, dig entrenchments, and erect parapets and gun batteries to create a contiguous defensive system.

Despite these exertions, he complained that not one-third of the work had been completed in time.

Sketch of the Residency and Palace at Lucknow, 1857

Chinhat

The Siege of Lucknow began in earnest following a failed attempt to forestall it. On 30 June, Lawrence led a force out to engage the rebels, but suffered a bloody reverse at the Battle of Chinhat.

Badly weakened, and aware that no imminent help would be arriving from the outside world, the British had no choice but to retreat to the Residency buildings, hunker down and defend their positions to the utmost.

Heavy odds

The defenders could muster only around 1,700 troops - just over half of them British - to protect their mile-long perimeter and the 1,300 civilians who had now taken refuge in the Residency. Among them were hundreds of women and children.

Although poorly led, the rebels numbered over 8,000 and would grow in strength as the siege progressed.

Over the coming weeks and months, the besieged garrison would suffer appallingly. Mercifully for Fulton, his family had been sent away to Simla in the far north, where many of the British stationed in India took refuge during the hot summer months.

Bombardment

After surrounding the Residency, the rebels commenced a bombardment of artillery and musket fire, which Fulton recorded as ‘the most infernal I ever experienced’. While their accuracy was mediocre, the sheer volume of fire resulted in many British casualties.

During the early days of the siege, the fraught situation was compounded by the carelessness of the inexperienced defenders, who often needlessly exposed themselves to danger.

Leadership losses

Lawrence was among the early casualties, mortally wounded by shell on 2 July. His successor, Major John Harris, was killed soon afterwards on 21 July.

Command subsequently fell to Brigadier Sir John Inglis of the 32nd Regiment of Foot, a British unit which formed the mainstay of the Lucknow garrison.

Morale

For Fulton, the early days of the siege were the most desperate. He was constantly needed and was kept frenetically busy.

After six days, he was at his wits' end and momentarily succumbed to a deep despair, writing: ‘I was so bewildered with calls in all directions, and want of sleep and fatigue had begun to tell their tale... for three hours I lay and gave in, in my heart, and thought we would be done for.’

However, he soon succeeded in rallying himself and restoring his faith in victory. He would later be widely praised by his comrades for his ability to remain cheerful and to inspire others with his leadership.

These qualities were sorely needed. The morale of the garrison became increasingly fragile as the siege progressed and was especially damaged on those occasions when a long-hoped-for relief force failed to arrive.

Mine warfare

Realising that the British would not be subdued by bombardment alone, the rebels adopted new tactics. Mining would prove one of their most persistent and dangerous methods of attack.

They made repeated attempts to dig tunnels under the Residency, where they could then deploy explosives to breach the defences. Unfortunately for them, their engineering skills were often found wanting.

During their first major effort, on 20 July, they blew their mine well short of their target, a key point known as the Redan. As the men advanced from the crater, they were badly exposed. Fulton recorded how they were ‘shot like sheep wherever they showed themselves’.

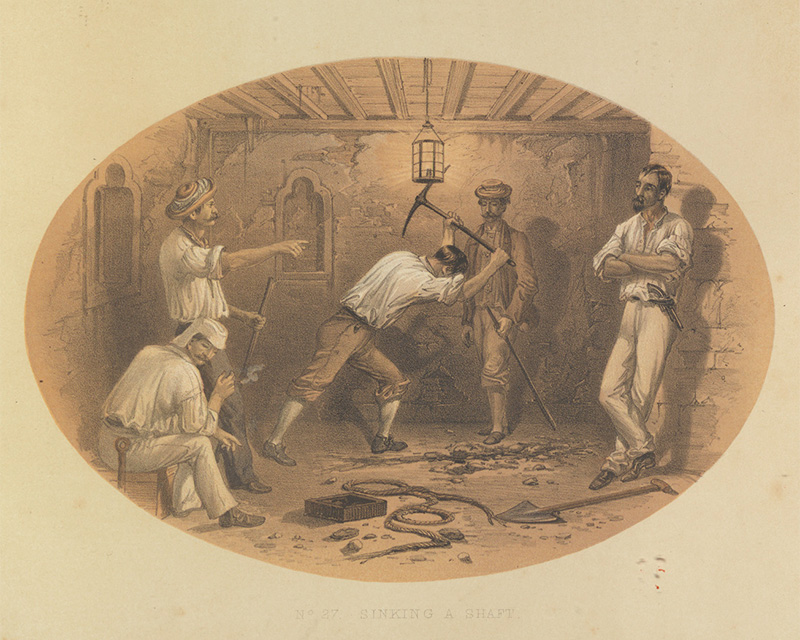

Defenders of Lucknow digging a counter-mine tunnel (Published in 'Sketches and Incidents of the Siege of Lucknow', 1860)

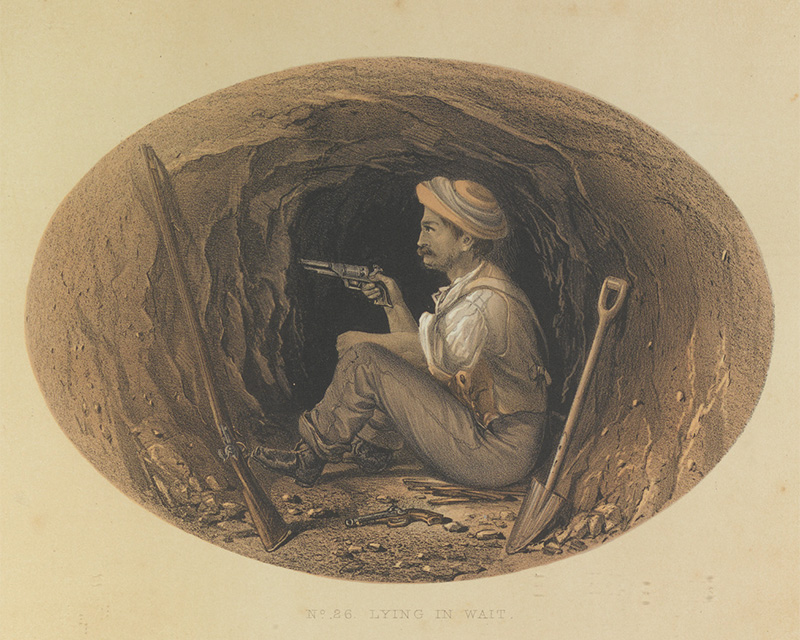

Fulton in a mine gallery, listening for enemy activity (Published in 'Sketches and Incidents of the Siege of Lucknow', 1860)

Counter-mining

More seriously for the besieging force, they faced an opponent who was well equipped to nullify this threat. Not only was Fulton himself a skilled engineer, he had the good fortune to be assisted by men of the 32nd Foot, a Cornish regiment in which many ex-miners served.

Under Fulton’s direction, extensive counter-mining operations were carried out. These involved digging tunnels that could then be used to break into or destroy those of the enemy, and prevent them from reaching their goal.

This was hot, hard, dirty and dangerous work. Fulton and his comrades often spent hours waiting patiently in mine galleries, listening out for any signs of enemy activity.

‘Some one looking for me asked one of the Europeans if I was in the mine. “Yes, sir,” said the sergeant, “there he has been the last two hours like a terrier at a rat-hole, and not likely to leave it either, all day.” Well I admit it is exciting, and mud, and dirt and water did not cool my ardour, but I got the whip hand of my enemies, and defeated a very serious attempt on a most important post filled with ladies and children!!!’Fulton recounting the efficacy of his mining activities — August 1857

Sorties

Fulton also led raiding parties to attack the buildings surrounding the Residency that were being used by snipers and artillery, or from where it was suspected that mines were being dug. These sorties were especially dangerous and could easily end in disaster.

While Fulton enjoyed some great successes, he also survived several close shaves. On one occasion, he took a tumble down an eight-foot trench. Another time, he was caught in the blast of an explosion, which left him severely concussed and nursing a badly wounded arm.

‘I ran across the street to the enemy’s house, fixed powder and hose. The troops got ready near me. The door was then blown open, and we rushed in and killed about 20, spiking a little gun. We saw no signs of mining. Everything went right, and only 2 men were wounded. I had neither sword, pistol, nor stick, having neglected all to carry the powder, etc., etc., which was heavy, and when I met two of the enemy in a door I was rushing into I had to run back ignominiously to bone a pistol. But it was too late then to shoot my friends. This job raised the spirits of the garrison and every one was pleased.’Fulton recounting a successful sortie — August 1857

In his element

Despite the dangers involved, Fulton clearly revelled in his work and took great pride and satisfaction in his many victories. Some encounters he even found highly amusing.

On one occasion, he defeated a tunnelling effort simply by shouting a warning to the enemy that they had been discovered: ‘I just put my head over the wall and called out in Hindustani a trifle of abuse, and “Bagho! Bagho!” - (Fly! Fly!) - when such a scuffle and bolt took place, I could not leave for half an hour for laughing.’

General assaults

The most dangerous moments were the massed attacks mounted by the rebels. During these crises, the defenders would have to fight desperately for every position, with even the sick and wounded mobilised to help.

Having learned that a British garrison at Cawnpore (now Kanpur) around 45 miles (72km) away had surrendered, and had then been betrayed and massacred, the British expected no mercy from the rebels and were desperate to avoid an equally grim fate.

Fortunately for them, the rebel attacks were poorly co-ordinated. Most of the attempts to breach the defence by mines or artillery bombardment failed, and they proved incapable of exploiting their few successes.

'Attack of the Mutineers on the Redan Battery at Lucknow, 30 July 1857'

Food

Vital though they were, these victories did nothing to alleviate the suffering of the besieged. As well as living day to day under enemy fire, food became a serious problem. Their rations, though adequate, were monotonous and lacked nutrition.

Fulton complained that the food was ‘wretched, worse cooked’, consisting of unpalatable stews and curries, and chapatis (flat breads) like ‘brass or lead’. Staples, such as eggs, milk, butter and fresh vegetables, were virtually unobtainable.

Disease

Even more grave was the risk of disease. The garrison lived cramped together in insanitary conditions, exposed to a harsh climate of intense heat and torrential monsoon rainfall. Combined with the lack of adequate medical supplies and facilities, this resulted in many people falling victim to illnesses, including smallpox and cholera.

Among them was Fulton’s commander, Major Anderson, who was stricken with dysentery early on in the siege and died on 11 August. Fulton himself was afflicted with liver trouble, although this proved less severe.

Death

Exposed to so many risks, Fulton’s chances of survival were always small. His luck finally ran out on 14 September, when he was killed by a round shot while inspecting a gun battery.

Lady Inglis - wife of Brigadier Inglis - recorded the tragic loss in her diary:

‘The shot took away the whole of the back of Captain Fulton's head, leaving his face like a mask still on his neck. When he was laid out on his back on a bed we could not see how he had been killed. His was the most important loss we sustained after that of Sir Henry Lawrence. Anyone except the brigadier [her husband] could have been better spared.'

'The Relief of Lucknow, 1857'

Relief

The timing of Fulton's death served to heighten its tragedy. Just 11 days later, a relief column led by Major General Sir Henry Havelock broke through. While this force was too weak to enable an evacuation, the reinforcements that Havelock brought ensured that the Residency could now be secured.

The Siege of Lucknow would drag on until 22 November, when a British column under Lieutenant General Sir Colin Campbell effected a breakthrough in sufficient strength to allow the garrison to withdraw.

One of the episodes that formed part of this final relief effort is worthy of special mention. On 16 November, Campbell’s troops were involved in fierce fighting for the rebel strongholds of the Secundra Bagh and the Shah Najaf. This resulted in the award of 17 Victoria Crosses (VCs) - Britain's most prestigious gallantry medal - the most for any battle in a single day.

Defender of Lucknow

Fulton's gallantry fully merited a VC. However, at this time, the award could not be conferred posthumously, and so his service and sacrifice went unrecognised. Today, he is a forgotten figure.

Nonetheless, he was lavished with praise by those who had lived and fought alongside him.

Brigadier Inglis wrote that he had fallen 'in a good cause, and in the active and zealous fulfilment of his duty, beloved and appreciated by all around’.

Martin Gubbins, one of the senior officials of the garrison, described him as ‘the life and soul of everything that was persevering, chivalrous and daring’, adding: ‘To Fulton all will join in conceding the title of “The Defender of Lucknow”.’

Access to the Archive

The National Army Museum provides public access to its library and archival collections via the Templer Study Centre. Over the coming weeks and months, we will be sharing more stories across our website and social media channels, highlighting some of the valuable personal insights these collections hold.