Explore more from In Their Own Words

In Their Own Words: Major General Sir Charles Melliss VC

18 minute read

Colonel [later Major General Sir] Charles Melliss VC, c1910

Father’s footsteps

Charles John Melliss was born in 1862 in Mhow (now a suburb of Indore in the Indian state of Madhya Pradesh).

His father, Lieutenant General George Melliss, was a professional soldier who served on the Staff Corps of the British Indian Army.

Charles also opted for a career in the military. He was originally commissioned into the East Yorkshire Regiment in 1882, before transferring to the Indian Army two years later.

Imperial soldiering

As a junior officer with the 9th Bombay Infantry, Melliss first saw action in East Africa during the M’Wele campaign of 1895-96. He then took part in the Kurram Valley and Tirah Operations on India’s North-West Frontier during 1897-98.

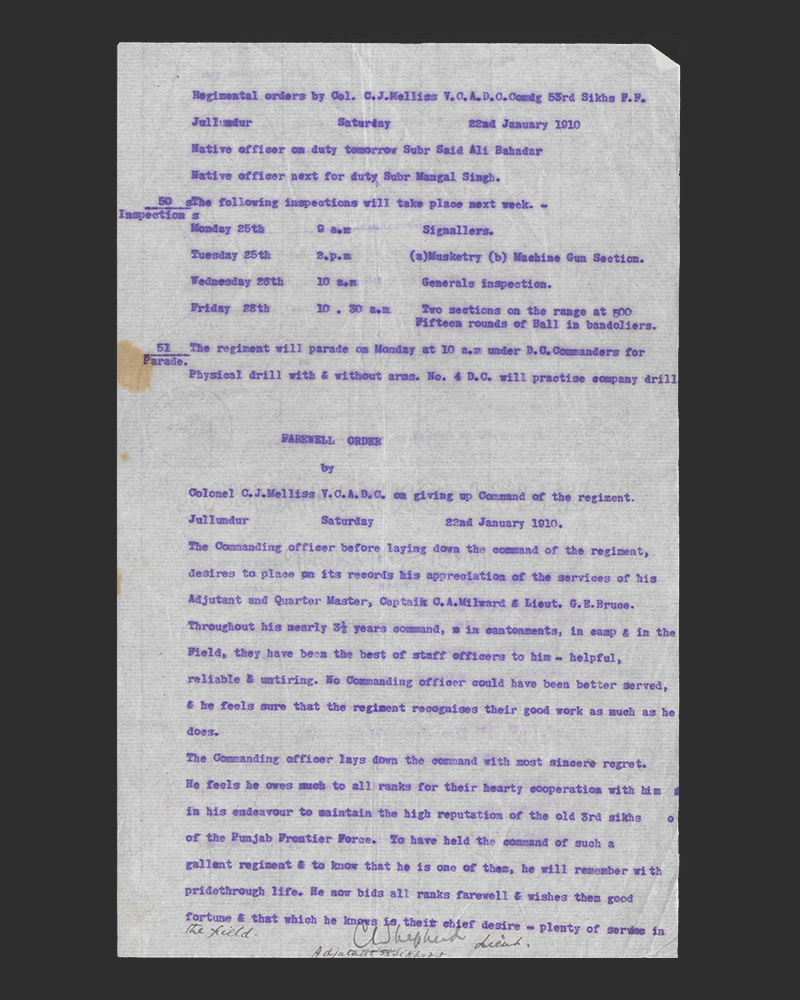

In the years that followed, he saw further service in Africa and India with a variety of units, rising to become commander of the 53rd Sikhs (Frontier Force), a regiment with which he formed a special bond.

Last regimental orders issued by Colonel Charles Melliss VC on laying down command of the 53rd Sikhs (Frontier Force), 1910

Lifesaving at sea

Melliss would undertake many brave actions during his career. A prime example came in May 1899, when he was travelling to West Africa by sea aboard the SS 'Sokoto’ to take up a command in the 1st Battalion of the West African Frontier Force.

Around midnight, a member of the ship's crew was lost overboard off Cape Coast Castle on the Gold Coast (now Ghana). Melliss leapt into the shark-infested waters to rescue him, an act for which he was awarded the bronze medal of the Royal Humane Society.

‘If I had not had the constant idea of sharks in my mind I shouldn’t have minded the thing a bit, as it was, I was in a deuced hurry to get out of the water.’Charles Melliss reflecting on saving the life of an overboard sailor, diary entry — 14 May 1899

Big-game hunting

Adventurous by nature, Melliss cultivated a love of big-game hunting in Africa and India. Lions and tigers were his favourite quarry, and such was his enthusiasm that he wrote about his experiences in a book entitled ‘Lion-Hunting in Somali-land’ (1895).

This was, of course, a highly dangerous pastime. During one fateful hunting expedition in East Africa in 1903, Melliss was severely mauled by a lion and nearly lost an arm. Remarkably, this did not deter him from continuing to pursue his passion.

‘The absolute bliss of that moment is, of course, indescribable. Here had I two lions, actually waiting for me, all to myself, a vast plain on all sides, clear of jungle as a lawn, not another bush even in sight. I was going to get them – or they get me – that was the only uncertainty in the whole thing. Could the situation have been more perfect? Impossible.’Charles Melliss recounting his enjoyment of lion hunting in Somaliland — 1895

Ashanti War

Melliss’s most daring exploits came during the Ashanti War of 1900, where he repeatedly displayed the highest level of gallantry.

Also known as the War of the Golden Stool, this was the fifth in a series of conflicts that the British had fought with the Kingdom of Ashanti (or Asante) in the central region of the Gold Coast. These campaigns had served to establish a tenuous British control over the Ashanti people during the previous century.

This time, the pretext for war was a grave diplomatic blunder committed by the colonial governor, Sir Frederick Hodgson. In March 1900, during a visit to the Ashanti capital, Kumasi, Hodgson demanded to sit upon the sacred golden stool, an object believed to embody the soul of the Ashanti nation. Already plotting to rebel, the Ashanti seized upon this outrage to launch a full-scale uprising.

Rescue mission

Holed up in the British fort in Kumasi, Hodgson, along with his wife and retinue, endured a grim siege. They succeeded in breaking out in June, but a skeleton force remained to hold the fort. Meanwhile, an expedition under Colonel Sir James Wilcocks had been despatched to rescue them.

The relief force was composed of a variety of Britain's African Imperial units. Prominent among them were soldiers of the West African Frontier Force (WAFF), a recently established formation made up of men recruited from Nigeria, the Gold Coast, Sierra Leone and The Gambia. Intended mainly to police and defend these colonies, the WAFF would later see extensive service across Africa and in Southeast Asia.

After a challenging advance through hostile country, Wilcocks’s force reached Kumasi in early July, breaking through to the fort just as it was on brink of surrender. Having safely evacuated the remaining garrison, the British undertook further operations to put down the rebellion and re-assert control.

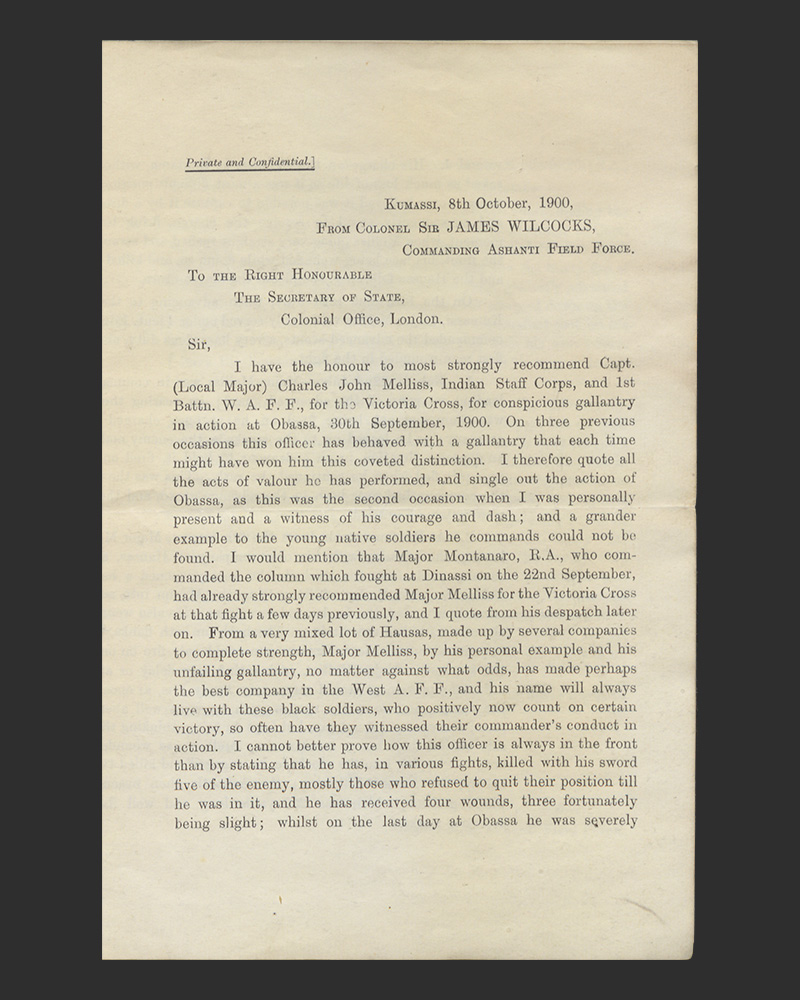

Victoria Cross

As a company commander with Wilcocks’s force, Melliss played his full part in the campaign. He was often in the thick of the action and was wounded on several occasions.

His most outstanding contribution came during one of the final engagements of the war, fought on 30 September at Obassa (now Obuasi), where the British encountered a formidable enemy position. Melliss led a valiant charge and was wounded in fierce hand-to-hand combat with an Ashanti soldier.

For his courage during this action, and throughout the campaign, Melliss received the Victoria Cross, Britain’s highest award for gallantry.

‘On the 30th September, 1900, at Obassa, Major Melliss, seeing that the enemy were very numerous, and intended to make a firm stand, hastily collected all stray men and any he could get together, and charged at their head, into the dense bush where the enemy were thick. His action carried all along with him; but the enemy were determined to have a hand-to-hand fight. One fired at Major Melliss, who put his sword through the man, and they rolled over together. Another Ashanti shot him through the foot, the wound paralysing the limb. His wild rush had, however, caused a regular panic among the enemy, who were at the same time charged by the Sikhs, and killed in numbers. Major Melliss also behaved with great gallantry on three previous occasions.’Victoria Cross citation for Major Charles Melliss — 1900

Mesopotamia

By the outbreak of the First Word War (1914-18), Melliss had attained the rank of major general and, in October 1914, was made commander of the newly formed 30th Indian Brigade. During 1915-16, he would see extensive service in Mesopotamia (now Iraq).

At the time, this region was controlled by the Ottoman Empire (centred on modern-day Turkey), which had entered the war on the side of Britain’s enemies in November 1914.

To demonstrate its power in the Middle East, and to secure access to vital oil supplies, Britain immediately proceeded to land a force at the head of the Persian Gulf and mount an offensive inland towards the southern Mesopotamian city of Basra.

A disaster in the making

This campaign held many grave risks. The initial force was small, composed only of units from the 6th (Poona) Indian Division under Lieutenant General Sir Arthur Barrett. Objectives were unclear and authority for the conduct of the campaign was poorly delineated between the Indian government, which exercised local control, and the British government, which held overall strategic direction.

Most seriously, planning for the campaign had been of the worst order, and little thought had been given to the logistical and medical capabilities that would be required in this inhospitable region.

Initial success

Despite these problems, the campaign enjoyed initial success. The Ottomans were unprepared for an invasion and Basra was swiftly secured.

This was followed up by the capture of Qurna (now Al-Qurnah), a strategic position further north at the confluence of the region’s two great rivers, the Tigris and the Euphrates.

Lieutenant General Sir John Nixon, 1912

Counterstrike

In April 1915, the Ottomans launched a counterattack, striking at the 6th Division’s camp at Shaiba, 8 miles (13km) south-west of Basra.

At this crucial juncture, the British command was in transition. Lieutenant General Sir John Nixon had arrived to take command of an expanded force, which now included Major General George Gorringe’s 12th Indian Division. Arthur Barrett had departed, but his replacement, Major General Charles Townshend, was not yet in post.

Melliss, who had only just arrived himself, was ordered to proceed to Shaiba to take command.

Major General Charles Melliss VC and staff in Mesopotamia, 1915

Shaiba

Melliss’s advance to the camp at Shaiba, accompanied by reinforcements, was severely hampered by seasonal floods which had inundated much of the surrounding area. His party arrived, under fire, in a flotilla of canoes to find a dangerous situation.

The British had succeeded in holding off the initial Ottoman attack, but were heavily outnumbered and surrounded on three sides. Taking charge, Melliss succeeded in organising a counterattack that drove the enemy completely from the field.

Touch and go

The Battle of Shaiba was hard fought and close run. In a letter to his wife, Kathleen, Melliss described just how precarious the affair had been.

He also revealed the heavy burden of responsibility that he felt for the lives of his men, telling her that he had spent the night worrying ‘if I had been rash & foolish & had thrown away good brave fellows in vain’.

‘I never want to go through the anxiety of some of that time, reports came into me of heavy losses on all sides & doubt if further advance was possible. I had thrown my last man into the fight - it still hung very doubtful... At last came a time when word came that our gun ammunition was running out! There was nothing for it but prepare plans for retiring (can you imagine my feelings!) ... When, to my joy, a report came to me that the Dorsets [Dorsetshire Regiment] & others had carried the enemy’s first line of trenches some 900 [yards?] in front of the woods & they were on the run. Can you imagine how thankful I felt.’Charles Melliss, in a letter to his wife, describing his feelings about the close-run battle of Shaiba — 22 April 1915

A harsh environment

In the months that followed, British objectives in Mesopotamia began to widen in scope under the ambitious leadership of Sir John Nixon.

Melliss’s brigade took part in operations as part of Gorringe’s 12th Indian Division, notably undertaking an advance along the Euphrates in June and July.

In letters to his wife, Melliss described the challenges of campaigning in this forbidding region. Intense heat, flies, mosquitos and sandstorms made daily life miserable for the troops and resulted in many sickness casualties.

‘We have had a pretty hard time of it, the heat has been great & the flies in swarms & never cease to worry from dawn until dark & dust storms in considerable frequency complete the picture. I doubt if I have ever had so trying a time in any show I have ever been in, or perhaps at 52 I feel it more, but the great heat & flies are a terrible combination, it is hard to put a morsal into your mouth for fear of swallowing flies that cluster on it & all the time swarms buzzed round one’s eyes, ears, & nose & there is not a tree or bush in the country for shade.’Charles Melliss, in a letter to his wife, describing the harsh conditions in Mesopotamia — 21 May 1915

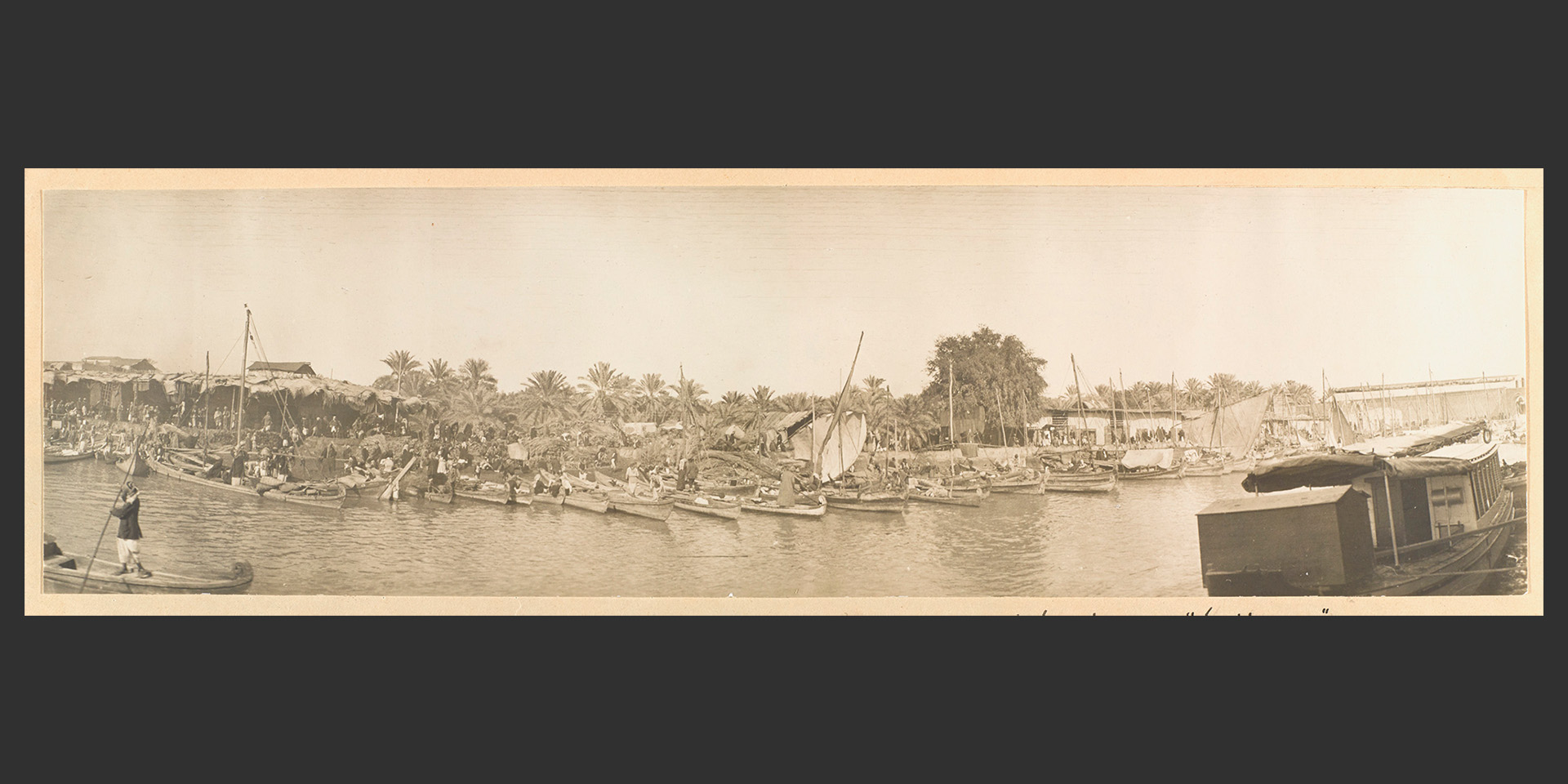

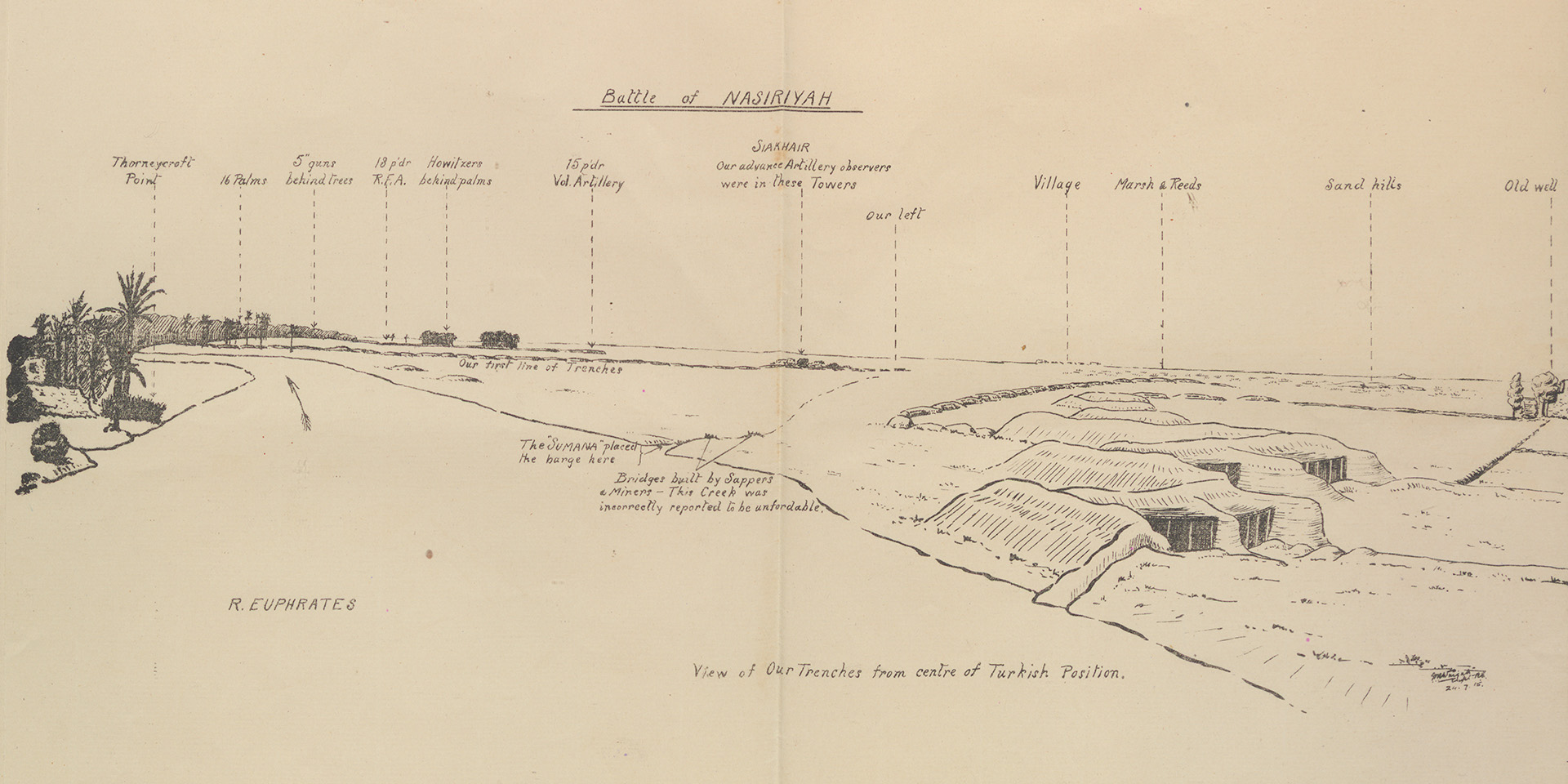

Nasiriyah

Their objective on the Euphrates was Nasiriyah, a significant administrative centre that would help secure control of the whole vilayet (or province) of Basra.

The advance upriver proved slow and arduous. The area around Nasiriyah was a quagmire, which greatly hampered the British force’s ability to manoeuvre.

During the series of assaults required to capture the town, the British position became critical. Success was only achieved through dogged determination and with the aid of substantial reinforcements.

A sketch of British trenches at the Battle of Nasiriyah, 1915

Strained relations

Melliss’s letters from this period also reveal his bitter criticisms of Gorringe’s leadership. Holding him responsible for their heavy casualties at Nasiriyah and for letting the retreating Ottoman force escape, Melliss concluded: ‘He is a rotten general & we all felt a great lack of confidence in him.’

Elsewhere, he recorded a spat between the two, which had resulted from Melliss's decision to advance into the town first - an act which Gorringe regarded as ‘subversive to discipline’.

Exhausted and ill from the strain, Melliss was granted a period of leave in India to rest and recuperate.

‘Falling into deep swamps up to your neck in hot mud as I did several times the other day does not help one to command.’Charles Melliss, in a letter written to his wife during the advance to Nasiriyah — 7 July 1915

Townshend’s Regatta

The operation along the Euphrates had been launched shortly after a separate offensive undertaken by Townshend’s 6th Division up the Tigris. This too was intended to cement British hold over Basra.

With much of the region still waterlogged, Townshend assembled a bizarre fleet of assorted vessels - later christened ‘Townshend’s Regatta’ - to undertake the advance.

This improvisation gave rise to serious logistical problems. However, Townshend enjoyed remarkable success, breaking through the Ottoman position at Qurna and capturing the town of Amara, over 85 miles (137km) to the north.

Kut

Greatly encouraged, Nixon secured permission to mount another offensive. In September, he ordered Townshend to advance to the town of Kut-Al-Amara, a further 120 miles (193km) up the Tigris. Defeating the Ottoman defenders with a bold plan of attack, Townshend was again crowned with success.

Kut was occupied and became an important British base. But the victory was marred by the Ottomans’ ability to withdraw their force intact.

Baghdad

In a fateful decision, the British now succumbed to the temptation to mount yet another advance and attempt to take the city of Baghdad. This was an objective that Nixon and Lord Hardinge, Viceroy of India, had been eyeing for some time.

Divided and uncertain about the enterprise, the British government ultimately gave its sanction on the basis that capturing this fabled city would greatly boost British prestige in the Arab world.

The Mosque at Kazimain, north of Baghdad, 1917

Baghdad from the air, 1918

Ctesiphon

Townshend’s force was too small for such an operation. What's more, it was now situated at the end of a long and tenuous supply line, which made any further advance very risky.

Despite this vulnerability, in November 1915, the 6th Division engaged the Ottomans in a desperate battle at Ctesiphon, about 20 miles (32km) south-east of Baghdad.

By this time, Melliss had returned from India and joined Townshend’s force. Taking command of a mixed ‘flying column’ of cavalry and infantry, Melliss led a wide flanking attack intended to deliver a crushing blow to the Ottomans.

Pyrrhic victory

Like other aspects of the plan, Melliss’s attack failed. The British were obliged to cling on grimly until the close-fought engagement ended with an Ottoman withdrawal.

However, Townshend’s force had suffered many casualties and was incapable of exploiting this success. Moreover, the situation rapidly deteriorated when news came in that the Ottomans had been reinforced and were on the advance.

Now under severe pressure, the 6th Division embarked on a gruelling withdrawal to Kut, where Townshend chose to dig in and accept the risk of a siege.

Under siege

In the first week of December 1915, the Ottomans invested the town of Kut, beginning an ordeal for the beleaguered garrison that would last for the next five months.

In a long and detailed diary-letter to his wife, Melliss documented daily life under siege and recorded the many hardships and dangers that the men endured.

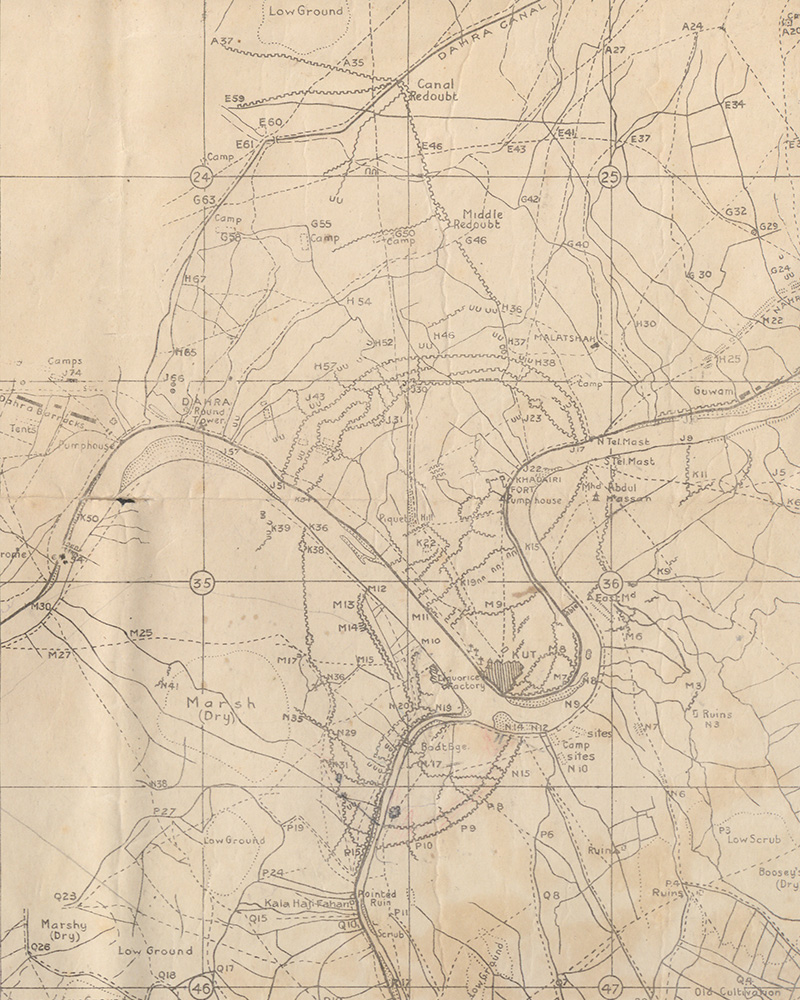

Military map of the area around Kut, Mesopotamia, 1916

Bombardment

Hoping to break the British position at Kut, the Ottomans mounted a series of assaults that culminated in a concerted attack on Christmas Eve. When this failed, they resorted to shelling and sniping, also tightening their blockade to cut off any help from the south.

The Ottoman bombardment took a steady toll in terms of casualties and placed the men of the garrison under continuous strain. Melliss experienced several near misses and recorded many other deaths and injuries from shells and bullets.

‘A noisy night last night much firing & a fair amount of shelling. Shells fell near the house & several bullets came into the house. 2 into my room [illegible] the window above my barricade of sandbags. I was awakened by splinters of plaster & wood falling on me but the bullets passed well above my bed & entered the wall. This is not altogether pleasant.’Charles Melliss, in a letter to his wife, recounting a near miss during the siege of Kut — 29 December 1915

Privations and suffering

Conditions inside the Kut garrison were harsh and got progressively worse. Although cooler, the winter brought torrential rain, which flooded out the trenches and made life miserable for the men.

Food became increasingly scarce and monotonous, eventually becoming restricted largely to bread and horse meat. This was a particular problem for the Indian soldiers, who were reluctant to eat horse on religious grounds.

Equally serious were the problems caused by the inadequate medical facilities. It was a constant struggle to cope with the steady stream of wounded and the rising cases of sickness caused by poor diet and hygiene.

‘It is horribly wet cold & gloomy & the poor men are in a dreadful state perishing with cold & wet.’Charles Melliss, in a letter to his wife, recounting the suffering of the troops in winter during the Siege of Kut — 21 January 1915

A clash of personalities

As a senior commander, Melliss was in frequent contact with Townshend. His letters provide a unique perspective upon this eccentric and controversial commander.

Like many who met Townshend, Melliss found him convivial company. However, he was bitterly critical of his abilities as a commander, decrying him as arrogant, incompetent and out of touch with the troops.

A notable run-in between the two came in late January, when stocks of provisions started to run low and Townshend began contemplating surrender or a breakout. Melliss recalled having to impress upon Townshend the importance of carrying on, using a newly discovered stock of grain and by slaughtering their transport animals.

In a heated exchange, Melliss informed Townshend that ‘it was our duty to our country & to our comrades to hang on here as long as possibly & that if he would not listen he should have it in black and white, meaning I would put it on the record’. This threat, Melliss believed, convinced Townshend to back down.

Major General Sir Charles Townshend, c1918

‘Townshend is a hopeless incapable dreamer & ass – vain as a peacock & full of military history comparisons, but as a practical soldier one’s grandmother would be as good. Sometimes one doesn’t know whether to laugh or cry at his incapacity. He never goes near the men or rarely – never goes near the front line of trenches & sees things for himself.’Charles Melliss, in a letter to his wife, criticising his superior, Charles Townshend — 25 December 1915

Surrender

Unlike Townshend, Melliss often visited the men in the front-line trenches and his presence did much to boost their morale. However, his letters document the deepening gloom that set in as repeated relief attempts launched by British forces from the south failed to break through and the situation in Kut continued to deteriorate.

Melliss was added to the ever-growing list of sickness casualties, spending the latter part of the siege in hospital.

By the end of April 1916, the garrison was on the brink of starvation and Townshend was finally compelled to surrender. The defeat at Kut is regarded as one of the worst in British military history.

Death march

The 13,000 men of the 6th Division were taken as prisoners of war. This experience was to be particularly traumatic for the other ranks and auxiliary personnel, who now faced the terrible ordeal of a forced march across hundreds of miles of difficult terrain to the Ottoman heartlands of Anatolia (in modern-day Turkey).

Exposed to the harsh climate and deprived of food, water and medical care, thousands would perish during this bitter journey. Many of those who survived would go on to die in the primitive Ottoman prison camps.

Contrasting reputations

Accepting preferential treatment from his captors, Townshend allowed himself to become detached from his troops and to live in relative comfort. This created the impression that he was more of a guest than a prisoner and that he was indifferent to the grim fate of his troops - a perception that would later damage his reputation.

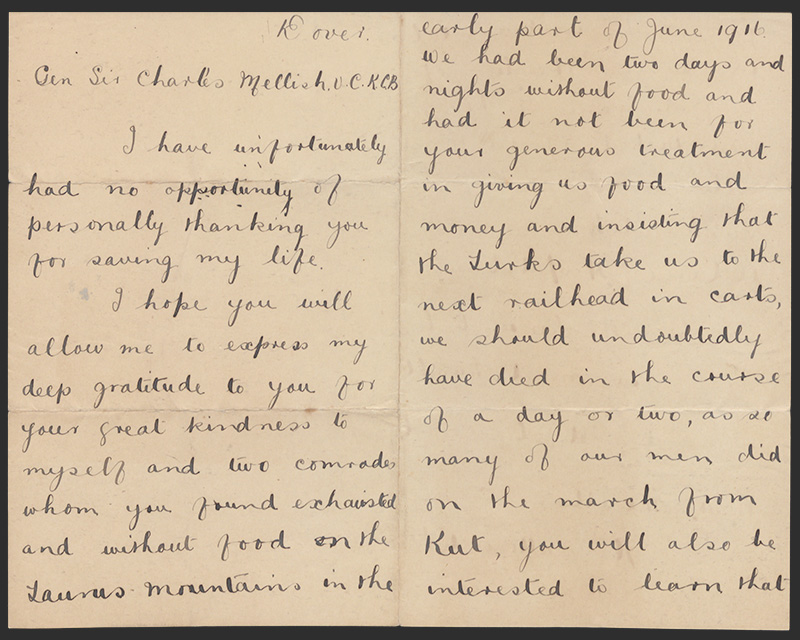

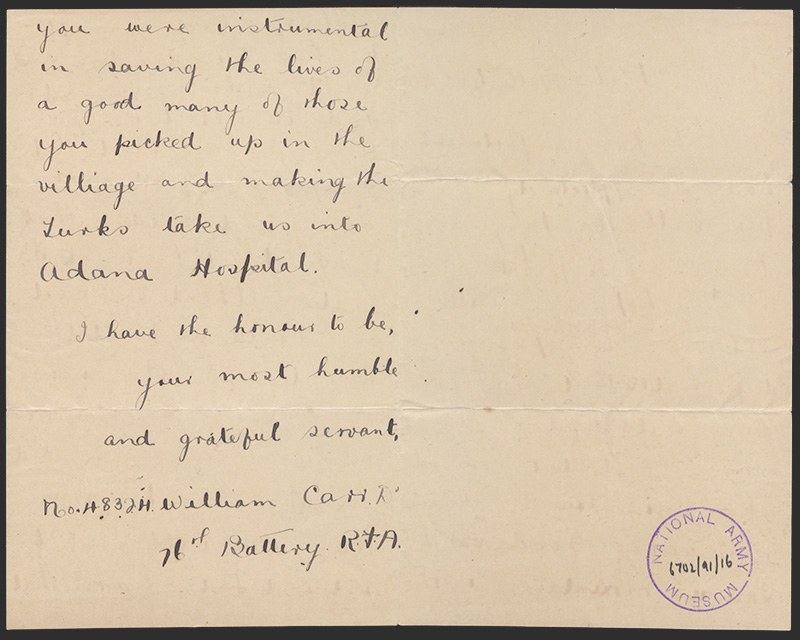

Melliss, by contrast, took great pains to assist the men. He rescued many from the brink of death along the march route and then wrote vociferously to the Ottoman authorities complaining about their treatment and trying to improve their living conditions. For these actions, he received the enduring gratitude of the survivors.

Letter to Melliss from Gunner William Carr of the Royal Artillery, thanking him for saving the lives of him and his comrades during their march from Kut to Anatolia, c1920

Breaking point

Melliss described the grim fate of the prisoners in a letter to the Secretary of State for War sent during his captivity in the city of Broussa (now Bursa) in 1917.

This letter also reveals the terrible toll that captivity had taken on Melliss's own health. He relates how his heart and nerves have been badly affected and that he has nearly reached breaking point from the mental strain.

‘I feel it beyond my powers of description to convey to you a picture of what I saw at some of the various halting places en route... I came across parties of our men, who were too exhausted to go further. They were lying about under a shelter or in any mud hovel given to them, some on the bare ground – others lucky to possess a blanket – many half clothed and without boots, which they had sold to purchase milk to keep life within them, there they lay in all stages of dysentery and semi starvation. Many terribly emaciated, some almost living skeletons, some dying, some dead.’Charles Melliss, in a letter to the Secretary of State for War, describing the fate of the prisoners taken at Kut — 15 August 1917

Retirement

Following his repatriation at the end of the war in 1918, Melliss was granted the honour of Knight Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George (KCMG) in recognition of his service.

He retired from the Indian Army in 1920, but was given the honorary appointment of Colonel of the 53rd Sikhs (Frontier Force), which he held until 1934.

He died in Camberley, Surrey in 1936, at the age of 73.

Access to the Archive

The National Army Museum provides public access to its library and archival collections via the Templer Study Centre. Over the coming weeks and months, we will be sharing more stories across our website and social media channels, highlighting some of the valuable personal insights these collections hold.