Camp followers and impostors

For centuries, women have joined men on military campaigns. Until the 1850s, they held various unofficial roles in the Army as wives, cooks, nurses, midwives, seamstresses, laundresses and even prostitutes. They lived and worked with a regiment and sometimes travelled abroad with it. These women played a significant role in caring for the physical and emotional wellbeing of soldiers.

At the time, war was strictly seen as men's work. But that didn't stop some women from wanting to take part. There are several well-known cases of women disguising themselves in order to fight. However, their experience was far from the norm.

1639-51

Civil Wars of Britain

1688-1713

Nine Years War and War of the Spanish Succession

1740-48

War of the Austrian Succession

1815

Battle of Waterloo

1813-64

A surgeon of the Empire

Nursing

With the ongoing professionalisation of the Army in the second half of the 19th century, women found themselves increasingly excluded from service. However, one area where women's involvement flourished was through nursing.

Florence Nightingale revolutionised the nursing profession during the Crimean War (1854-56) and established its necessity by caring for sick and wounded soldiers. Professional, trained nurses returned to the battlefield in later conflicts and organisations were created to formalise their work.

1855

The Lady with the Lamp

1899-1902

Queen Alexandra's Imperial Nursing Service

1907

First Aid Nursing Yeomanry

War work for women

During the early 1900s, several quasi-military volunteer groups for women's work were established including the Women's Emergency Corps, the Women's Forage Corps, the Women's Defence Relief Corps and the Women's Land Army.

The outbreak of the First World War (1914-18) provoked a debate on women's roles in the conflict. The economic strain of the war meant that women were already working on the Home Front in factories. And volunteer groups like the Women's Legion cooked for the troops. Owing to manpower problems, the Army started looking for more formal ways to bring women into the fold.

21 July 1915

Jobs for women!

Summer 1916

Manpower problems

Spring 1917

Women on the Western Front

1917-18

WAACs at war

1918

Controller Alexandra Chalmers Watson resigns

6 February 1918

British women given the vote

April 1918

Queen Mary's Army Auxiliary Corps

Second World War

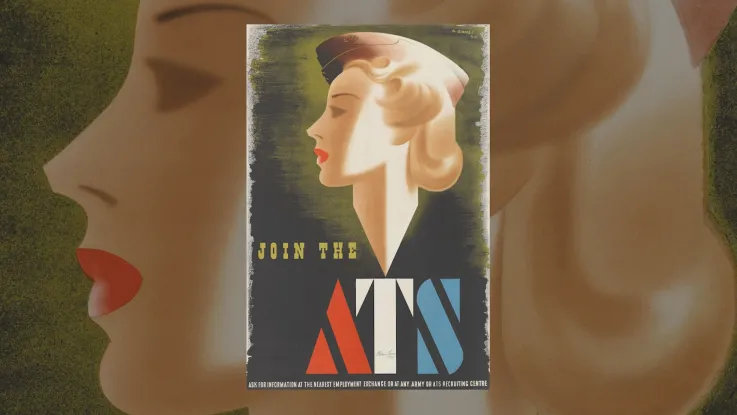

QMAAC had been disbanded in 1921, but it inspired the formation of the Auxiliary Territorial Service (ATS), which was established in September 1938. Women were still not allowed to fight in battle, but once again returned to supporting roles during the Second World War (1939-45).

They were cooks, clerks, drivers, radar operators, telephonists, anti-aircraft gunners, range finders, sound detectors, military police and ammunition inspectors. The Women's Royal Naval Service and the Women's Auxiliary Air Force were also established at that time. Women again went to work on the Home Front too, either in industrial roles, as before, or as part of the Women's Land Army.

July 1941

Auxiliary Territorial Service

December 1941

Conscription of women

February 1945

Royal service

8 May 1945

VE Day

Women's Royal Army Corps

The Women's Royal Army Corps (WRAC) was formed in 1949, absorbing the remaining troops of the ATS. It eventually included all women serving in the Army except medical and veterinary orderlies, chaplains and nurses.

Between 1949 and 1992, WRAC women served in over 40 trades in operations across the world including Cyprus (1955-59), Northern Ireland (1969-92), the Falklands (1982-83) and the Gulf (1990-91). Their many roles included patrolling with arms and explosive search dogs.

1 February 1949

Women's Royal Army Corps

March 1952

Harmonisation

1975

Supporting roles only

1991-92

Search dogs

1992

Disbandment

1992

Royal Irish Regiment

Women for combat roles

Following the disbandment of the WRAC in 1992, women were absorbed into the rest of the Army. But they were still largely restricted to support and medical positions.

Combat roles remained closed to the vast majority of female soldiers until 2016, despite the fact that women had already been present at the front for some time. Six women were killed in action in Iraq (2003-11), and another three in Afghanistan (2001-14). Some women had even served as combat medics and shown bravery under fire.

Much of the debate about female combat centred on the impact of gender integration on battle effectiveness. Many questioned whether female physical and psychological characteristics were suitable for combat, rather than looking at their overall contributions to teams and units.