Imperial Federation

In 1877, Lord Carnarvon, Secretary of State for the Colonies, was keen to extend British imperial influence in South Africa. He appointed Sir Bartle Frere as High Commissioner to help him establish a federation of British colonies and Boer republics.

Carnarvon’s policy required Frere to gain control over Zululand, an independent kingdom bordering Natal (a British colony) and Transvaal (a Boer republic). However, King Cetshwayo rejected Frere's demands for federation, as this would result in a loss of power, and refused to disband his Zulu army.

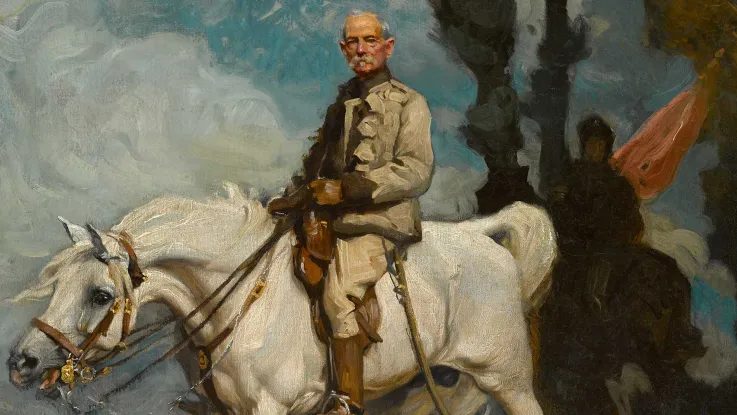

In January 1879, war began when a force led by Lieutenant-General Lord Chelmsford invaded Zululand to enforce Britain's demands.

Three columns

Lord Chelmsford split his invasion force into three columns. He planned to surround the Zulus and force them into battle before capturing the royal capital at Ulundi.

The right column crossed into Zululand near the mouth of the Tugela River to secure an abandoned missionary station at Eshowe as a base. The left column entered Zululand from the Transvaal and made for Utrecht.

Finally, the centre column, led by Chelmsford himself, crossed the Buffalo River at Rorke's Drift mission station to seek out the Zulu army.

‘If I am called upon to conduct operations against the Zulus, I shall… show them how hopelessly inferior they are to us in fighting power, although numerically stronger.’Lieutenant-General Lord Chelmsford — 1878

Formidable enemy

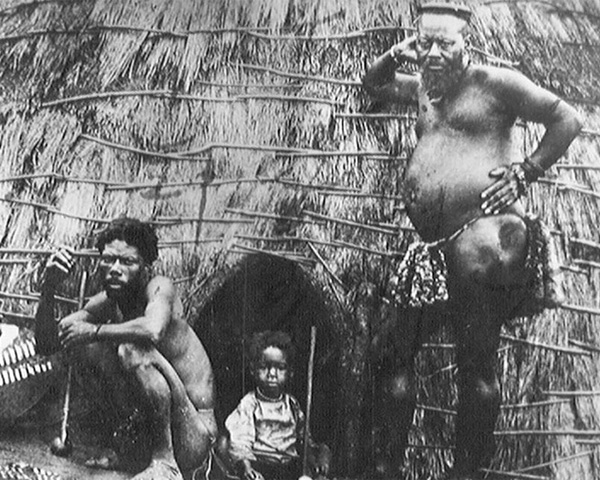

Fearing British aggression, Cetshwayo had already started to purchase guns before the war began. The Zulus now had thousands of old-fashioned muskets and a few modern rifles at their disposal. But their warriors were not properly trained in their use.

Most Zulus entered battle armed only with shields and spears. However, they still proved formidable opponents. They were courageous under fire, manoeuvred with great skill and were adept in hand-to-hand combat. Most of the actions fought during the war hinged on whether British firepower could keep the Zulus at bay.

‘March slowly, attack at dawn and eat up the red soldiers.’King Cetshwayo's orders to his troops at Isandlwana — 1879

Defeat at Isandlwana

On 22 January 1879, Chelmsford established a temporary camp for his column near Isandlwana, but neglected to encircle his wagons to strengthen its defence. After receiving intelligence reports that part of the Zulu army was nearby, he led part of his force out to find them.

Over 20,000 Zulus, the main part of Cetshwayo's army, then launched a surprise attack on Chelmsford's poorly fortified camp. Fighting in an over-extended line, and too far from their ammunition, the British were swamped by sheer weight of numbers. The majority of their 1,700 troops were killed. Supplies and ammunition were also seized.

The Zulus earned their greatest victory of the war and Chelmsford was left no choice but to retreat. The Victorian public was shocked by the news that 'spear-wielding savages' had defeated their army.

22-23 January

Rorke's Drift

22-23 January

Nyezane and Eshowe

31 January

Khambula

11 February

Chelmsford seeks reinforcement

28 March

Hlobane

29 March

Battle of Khambula

2 April

Gingindlovu

5 April

Relief of Eshowe

Gatling gun, Zululand, 1879

Politics and peace

The British government was concerned about the lack of military progress and possible Zulu threats to British territory in Natal. Orders were issued for Lord Chelmsford to be replaced by Sir Garnet Wolseley.

The Zulus were aware that Chelmsford was planning a second invasion and King Cetshwayo sent envoys to negotiate peace. But, eager to redeem himself before his replacement arrived, Chelmsford ignored Cetshwayo's pleas and invaded again at the end of May 1879. His reinforced army made steady progress, despite supply problems and constant skirmishing.

A royal scandal

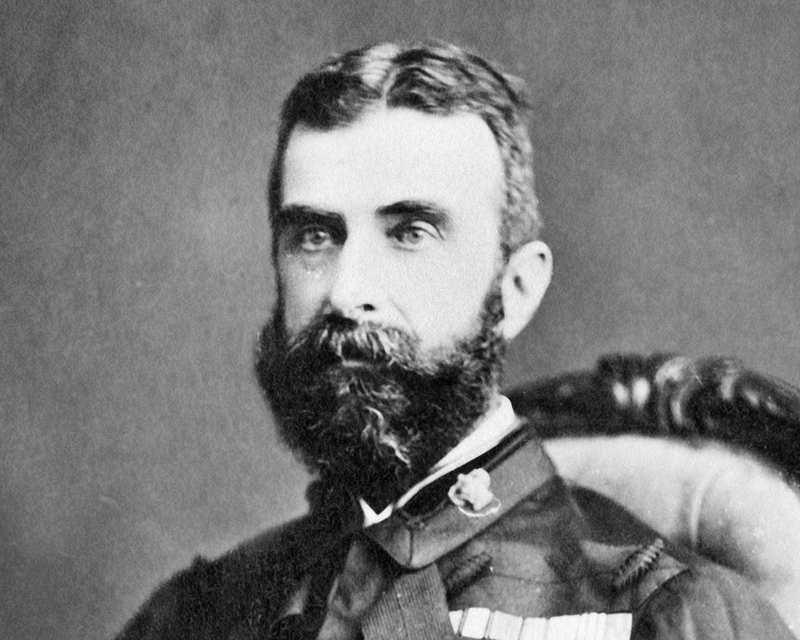

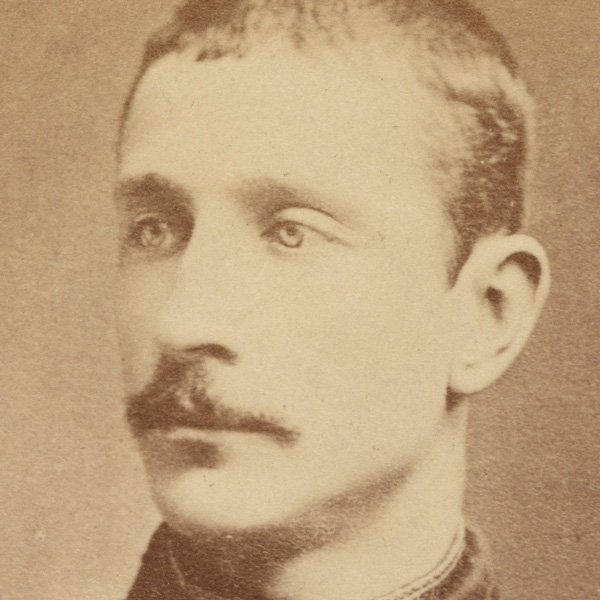

The French Prince Imperial, Louis-Napoléon - who had been exiled to England after his father, Napoleon III, was dethroned in 1870 - served on Lord Chelmsford's staff during the Zulu War.

He had only been allowed to go to South Africa after his mother, the Empress Eugenie, and Queen Victoria had intervened on his behalf. But this was on the strict condition that he be kept out of danger.

He was ambushed and killed near Ulundi on 1 June 1879, after setting out on a patrol without his full escort. His body was found with 18 spear wounds. It had also been ritually disembowelled. His death caused an international scandal.

Victory at Ulundi

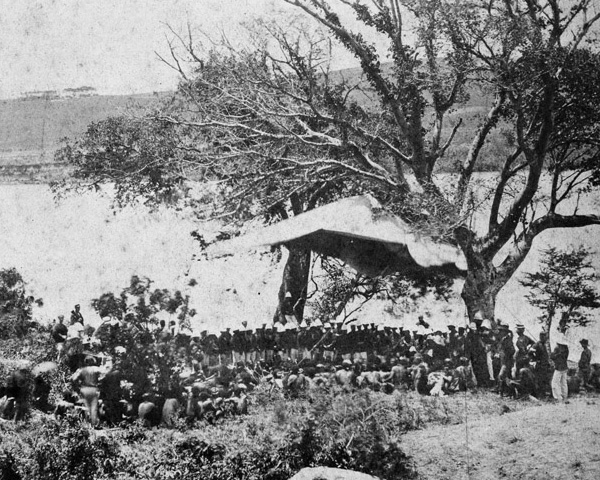

On 4 July, Chelmsford drew up his 5,000-strong army in a large square opposite Cetshwayo’s capital at Ulundi. Around 20,000 Zulus attacked in their usual fashion. But faced with Gatling guns and artillery, their brave charges soon petered out. The cavalry then drove the survivors from the field.

Around 6,000 Zulus had been slain for the loss of 10 men killed and 87 wounded. The British were so impressed by the courage of their opponents that they built a memorial to the Zulus at Ulundi along with their own.

Annexation

After the Battle of Ulundi, King Cetshwayo was hunted down and captured. The Zulu monarchy was suppressed and Zululand divided into autonomous areas.

Cetshwayo's possessions were seized, and he was exiled to Cape Town, and later London. In his absence, civil war ensued.

In 1883, the British attempted to restore order by returning Cetshwayo to his throne. However, his powers were now greatly reduced and he died the following year.

In 1887, Zululand was declared British territory and finally annexed to Natal ten years later.