Creative challenges

Jules George, a war artist working with the Ministry of Defence, travelled to Afghanistan in 2010 to draw troops on campaign. While embedded with the Army in Helmand Province, he endured the same hostile conditions as the soldiers serving there. But he also encountered an array of problems specific to his role as an artist.

Jules George sketching in Afghanistan in 2010

Original sketch for 'Battle, Afghanistan, 2010' (© Jules George)

Weather, enemy fire and equipment were just some of the challenges Jules had to overcome. The situation on the ground could change very quickly, meaning there was rarely time to focus on something long enough to draw it. The nature of the terrain also presented obstacles to his way of sketching.

Simply keeping hold of his work was sometimes tricky. Jules lost the contents of one sketchbook when he was knocked off his feet by the downdraft from a helicopter, gashing his drawing hand in the process.

‘It was the first time that I had literally drawn and walked at the same time, whilst also endeavouring to carefully follow the previous footsteps, only too aware of the possibility of stepping on an IED [improvised explosive device].’Jules George on painting in Afghanistan

On the spot

Given these difficulties, many paintings of conflict zones supposedly created on the spot have in fact often been finished later in the comfort of a studio.

Artists frequently bring together a number of perspectives or detailed studies sketched on location in order to create one composition on a canvas. They use devices to heighten drama or create dynamism while retaining the immediacy of the scene they witnessed.

The watercolour above, 'An East View of the Great Cataract of Niagara', is an example of this. Dating from 1762, it is inscribed: 'Done on the spot by Thomas Davies Capt Royal Artillery'. While we know that Captain Davies sketched Niagara Falls from life, it's unlikely that he completed his painting in that environment.

Surveying the landscape

Captain Davies carried out his sketches as part of a territorial survey. As Britain’s empire grew in the late 18th century, military engineers studied and drew the newly-captured lands to record their economic and military potential.

In 1767, the East India Company, which ruled large parts of the Indian subcontinent, created the Survey of India to help consolidate its territory. The work carried out by this agency led to the European discovery of Mount Everest, and is continued by the Indian civil services today.

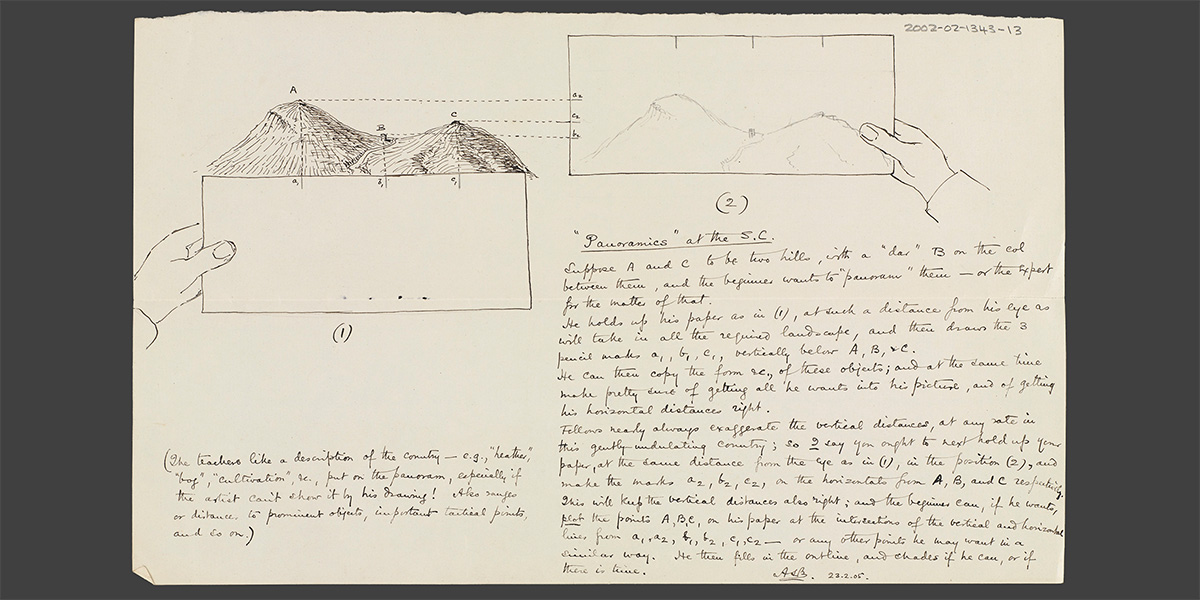

Notes on the method of drawing panoramas, by Archibald Crawford who taught mapping at the Staff College, 1905

An aid to military map-making

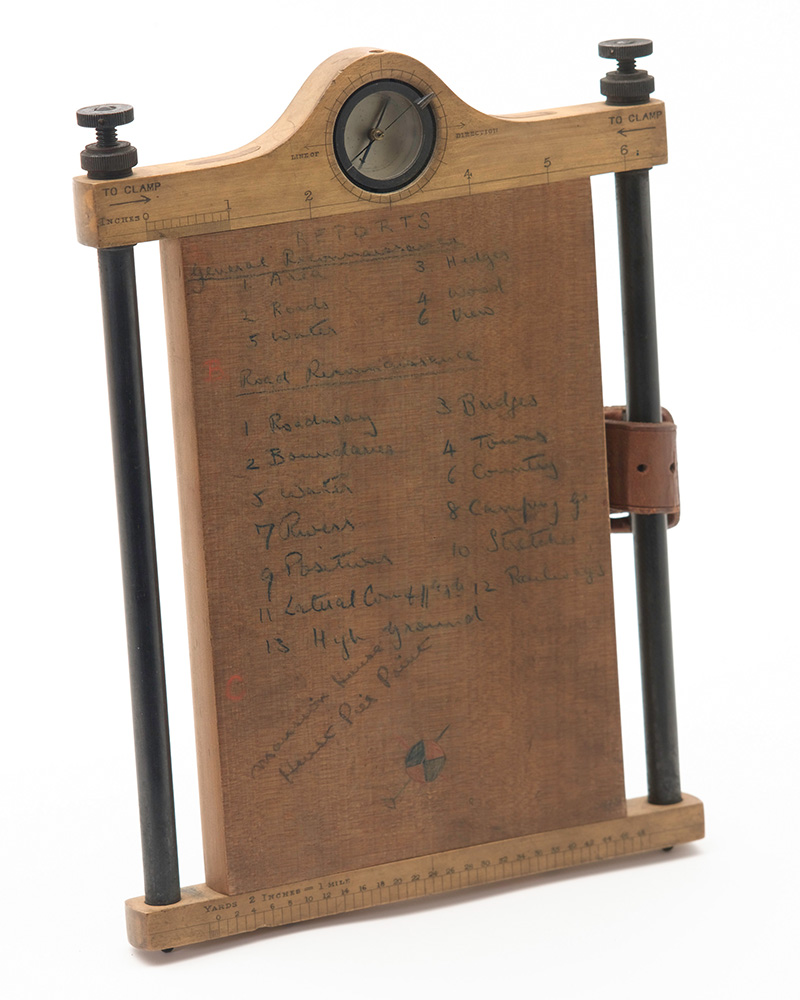

By 1833, a new School of Military Survey was established to train engineers in surveying, sketching and mapping. Around 1880, the military sketching or surveying board was introduced as an aid to military map-making.

The board was devised by Colonel WH Richards, a topographical instructor at the Royal Military College Sandhurst. It was intended to be used while riding - a leather strap attaches it to the user’s wrist.

Sketching boards were fitted with a compass and a clinometer, to measure the angle of tilt. Brass rollers on the sides held the paper steady. As a sketch was completed, these could be twisted to reveal more fresh paper.

Major Willoughby Verner patented a new version in 1887 with a scale at the bottom so that, when held in the hand, no other instruments were required.

Page from a sketchbook by William Barns Wollen, c1916

Shades of grey

Many of the artists who accompanied the Army to war used a technique called 'grisaille', painting entirely in shades of grey. By rendering the images in monochrome, they made it easier for engravers to transfer their pictures to printing blocks.

Some artists, such as William Barns Wollen, were so familiar with using this technique for their images for the press that they continued to use it for preliminary studies for oil paintings.

Colour on campaign

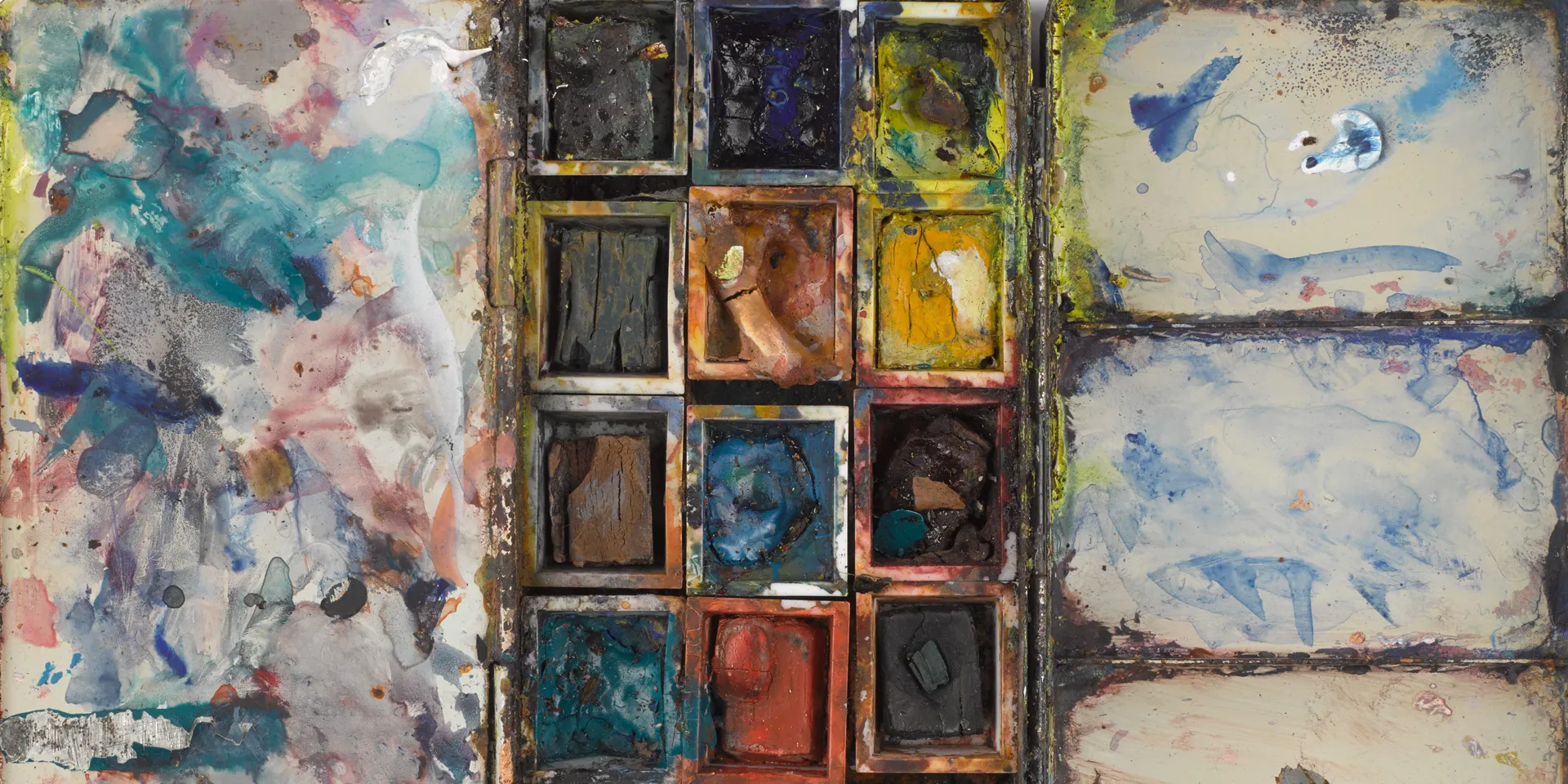

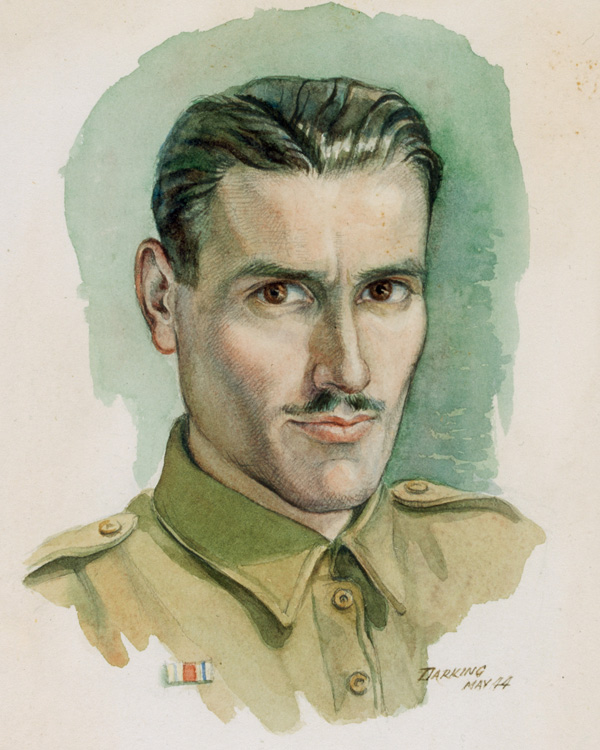

Other soldier-artists found ways to use colour in the midst of the action. The watercolour box pictured above was used by Sergeant Fred Darking when serving with the Royal Engineers during the Second World War (1939-45).

It measured just over 10cm x 5.5cm, and would have fitted easily into a pocket of his webbing equipment. Darking's watercolour pans have been well used and the fold-out palette retains evidence of the colours he mixed.

Fred Darking was born in Nottingham in 1911. He trained as a draughtsman and then worked as a commercial artist before the Second World War. In 1940, he enlisted and served in the Deception Unit of the Royal Engineers.

Darking worked with other painters, sculptors, architects, craftsmen and even magicians in the development of camouflage to make objects and soldiers ‘disappear’. Camouflage artists created designs of irregular, coloured shapes to blur the outline of objects and developed creative deception plans including inflatable tanks and dummy airfields and camps.

Although he was not an official war artist, the sketches that Darking produced in his spare time provide an important eyewitness record of the D-Day landings and subsequent campaigns through France, Belgium and Holland. He began to paint in order to help come to terms with his experiences of war. After the war, he set up an art school for demobilised soldiers.

Making do

Some soldier-artists, when short of materials, have resorted to using whatever is at hand to create their work.

On active service with the Chindits in Burma, Private Wilfrid Myers drew his fellow soldiers in the hilly jungle terrain. He sketched using camouflage cream or, as in the portrait below, 'Blanco' cleaning products.

Many soldiers have ended up drawing on army-issue forms or any other paper available. Similarly, some have painted on the lids of cigar boxes or discarded crates.

Douglas Farthing served in the Parachute Regiment for 23 years before retiring in 2008. Two years later, he returned to serve in a Territorial Army unit of the Royal Anglian Regiment. Wherever he was deployed, he carried a sketchbook in his kitbag to record his perspective of the reality of war. He also painted on the lids of crates and ammunition boxes.

‘I’m not sure whether it was an artistic response or a financial response, but it was quite a nice thing I was making things from what we used as soldiers.’Douglas Farthing on using unconventional drawing materials

Travelling light

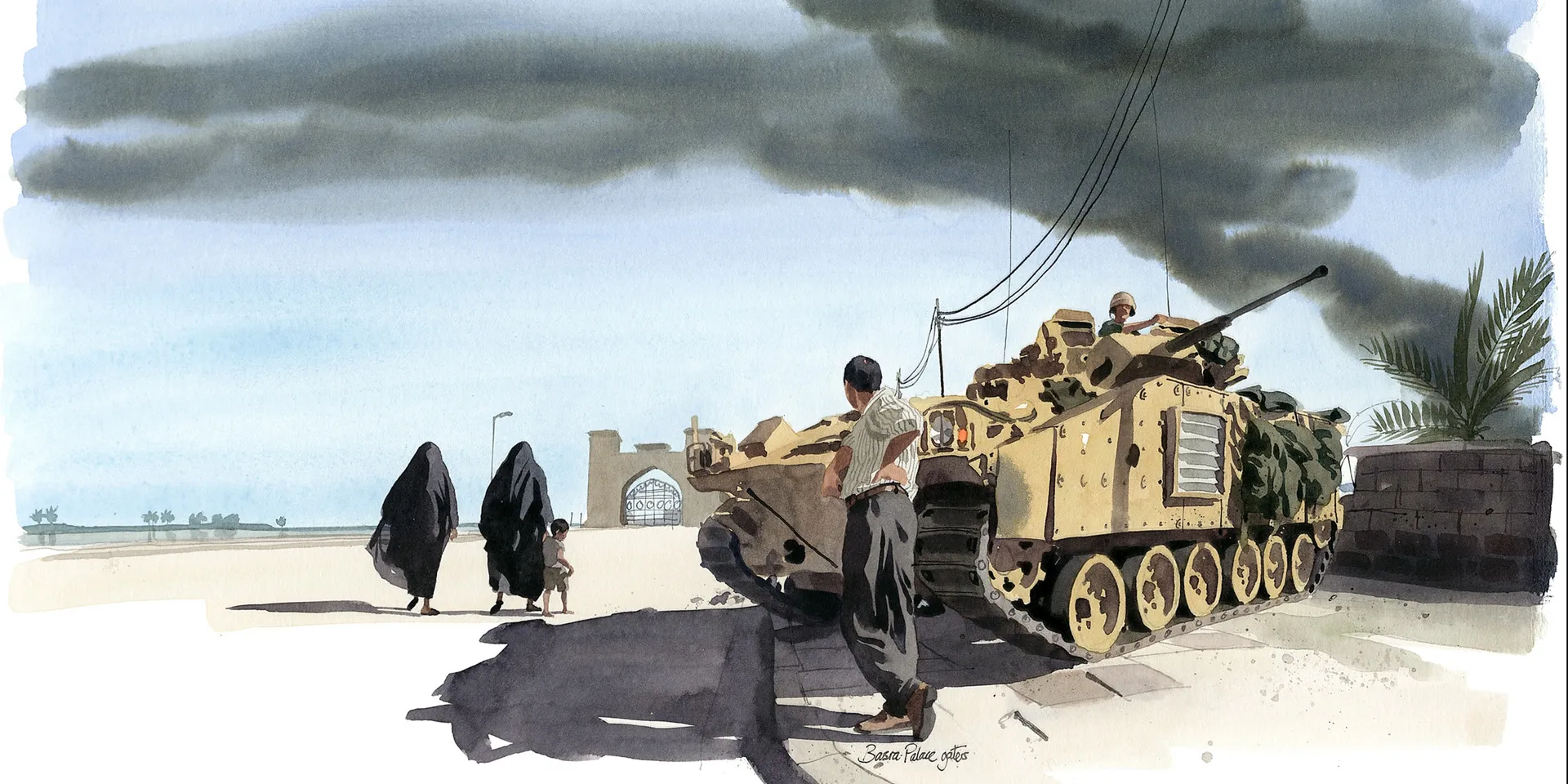

In March 2003, Matthew Cook was appointed war artist for 'The Times' and given a week to get ready for the impending war with Iraq. Already serving as a Territorial Army soldier, he also attended a short hostile environment training course before flying to Kuwait.

Matthew used a minimal kit while painting in Iraq in 2003, and again in Afghanistan in 2009. His tools included pens, pencils, brushes, a sketchbook and three pots of acrylic ink in primary colours, from which he mixed all the shades he needed to capture the scenes around him.

Unusually, Matthew used plastic airline food trays as palettes to mix his inks. Ever conscious of the need to carry as little equipment as possible, he even urinated in the water bottle used with this painting kit in order to save water!