Occupation

On 7 May 1945, after months of fierce fighting, the Germans agreed to Allied demands for unconditional surrender, finally ending six years of warfare that had left millions dead and much of Europe in ruins. The following day, Tuesday 8 May 1945, was declared 'Victory in Europe' (VE) Day, and marked the formal end of the European war. The Allies were now faced with occupying a conquered and destroyed nation.

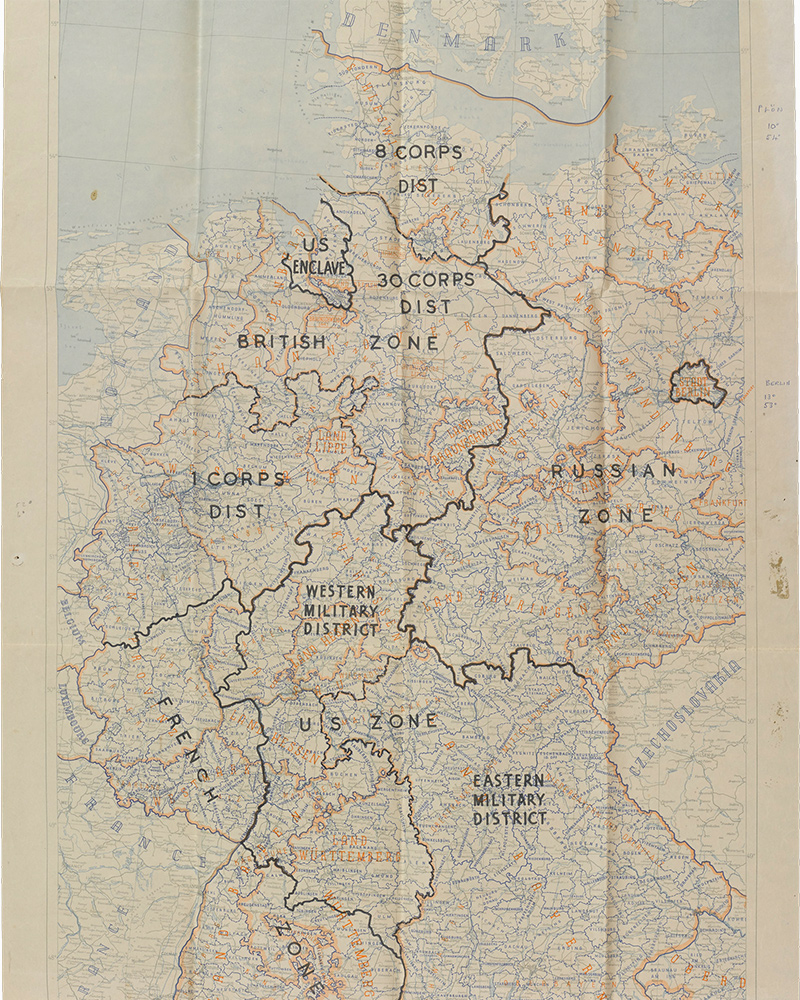

It had already been agreed that Germany and Austria would be divided into four occupation zones: Soviet, American, French and British. Each of the major powers was the sole political and legal authority in its zone.

The German capital of Berlin, despite being deep inside the Soviet occupation area, was also to be split into four separate zones. The four powers would also work together via the Berlin-based Allied Control Council, formed in August 1945, which would oversee matters relating to the whole of Germany.

BAOR

On 25 August 1945, Field Marshal Montgomery's 21st Army Group was renamed the British Army of the Rhine (BAOR). It was made responsible for the occupation and administration of the British Zone in north-west Germany. In this task, it was assisted by the Control Commission Germany (CCG). This consisted of British civil servants and military personnel. It took over aspects of local government, policing, housing and transport.

The BAOR’s headquarters were established in Bad Oeynhausen in North Rhine-Westphalia. Both here and elsewhere, it requisitioned German buildings for military administration and accommodation, exacerbating the housing shortage. Indeed, with around 800,000 Commonwealth soldiers in Germany by the end of 1945, finding barracks and camps for them all in a ruined country was major headache.

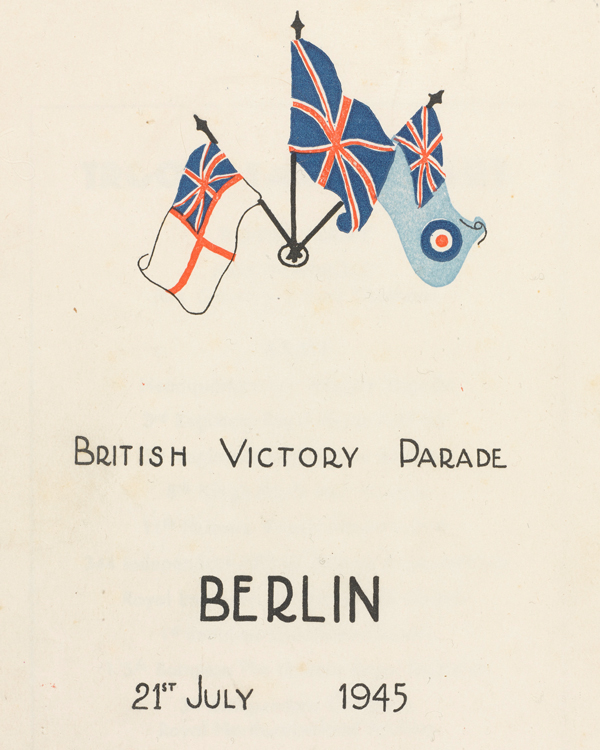

Celebration

On 21 July 1945, the British held a victory parade through Berlin to commemorate and celebrate the end of the war. Many other parades had already been held across the British zone.

While an integral part of the Victory in Europe (VE) celebrations, these events also helped enforce a sense of defeat on the Germans and served to remind them that they were occupied.

Last-ditch resistance

Following their victory, the Allies feared that Nazi fanatics might wage a partisan war against the occupation, and gather in the mountains of Bavaria and Austria, in the so-called 'Alpine Redoubt'. These concerns proved unfounded and were largely the result of German propaganda fooling Allied intelligence services.

Another last-ditch Nazi resistance effort, the Werewolf plan, was also something of a damp squib. This was aimed at encouraging acts of sabotage and reprisals against collaborators in areas occupied by the Allies. Despite its limitations, it was a useful propaganda device that helped convince the most ardent Nazi supporters to carry on fighting in the final weeks of the war.

In any case, the Allies took the threat seriously and had interned around 100,000 civilian suspects by the end of 1945. They also kept many German officers in prisoner-of-war camps for longer to prevent them supporting the Werewolf campaign on release.

The last Werewolf activities petered out in early 1947, with its operatives having failed to mobilise a war-weary population to support their doomed struggle.

War criminals

Thousands of men and women suspected of involvement in the concentration camp system and other crimes across Europe were rounded up by Allied forces. The key Nazi leaders were to be dealt with jointly by the main Allied powers, while the rest would be punished in those countries where they had committed their atrocities. Apprehending these lesser-known Nazis became the responsibility of the Allies depending on which zone of Germany or Austria they controlled.

Between November 1945 and October 1946, the Nuremberg military tribunal tried 24 leading Nazis and charged them with crimes against peace, war crimes and crimes against humanity. Eleven were executed and the others sentenced to varying terms of imprisonment.

Investigation teams

The BAOR was responsible for pursuing suspected war criminals in its zone of north-west Germany. It established the British Army War Crimes Investigation Teams (WCIT), which was assisted by other units, including the Special Air Service (SAS).

Among those brought to trial were the SS personnel of Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, which had been liberated by the British in April 1945. Those found guilty included Commandant Josef Kramer who was sentenced to death by a military court and hanged on 13 December 1945.

The most famous Nazi caught by the British was Heinrich Himmler, chief of the SS and one of the main architects of the Holocaust. He was arrested, while in disguise, at a checkpoint and taken to an interrogation camp near Lüneburg on 23 May 1945. Under interrogation, Himmler admitted who he was, but avoided trial by committing suicide with a concealed cyanide pill.

Political support for war crimes prosecutions soon declined. As relations with the Soviet Union deteriorated, it was considered more expedient to make friends with Germany rather than keep prosecuting its people and alienate them from the West. As early as April 1946, the British government was calling for cuts to the WCIT. Many investigating officers were demobbed without being replaced. By early 1948, only a handful of cases were being pursued.

By then, the WCIT had brought around 350 cases to trial involving over 1,000 accused Nazis. Of these, 667 were convicted of crimes and 230 sentenced to death. War crimes trials were also brought by many other countries, including the Soviet Union and Poland, but only a small fraction of guilty Nazis were ever punished.

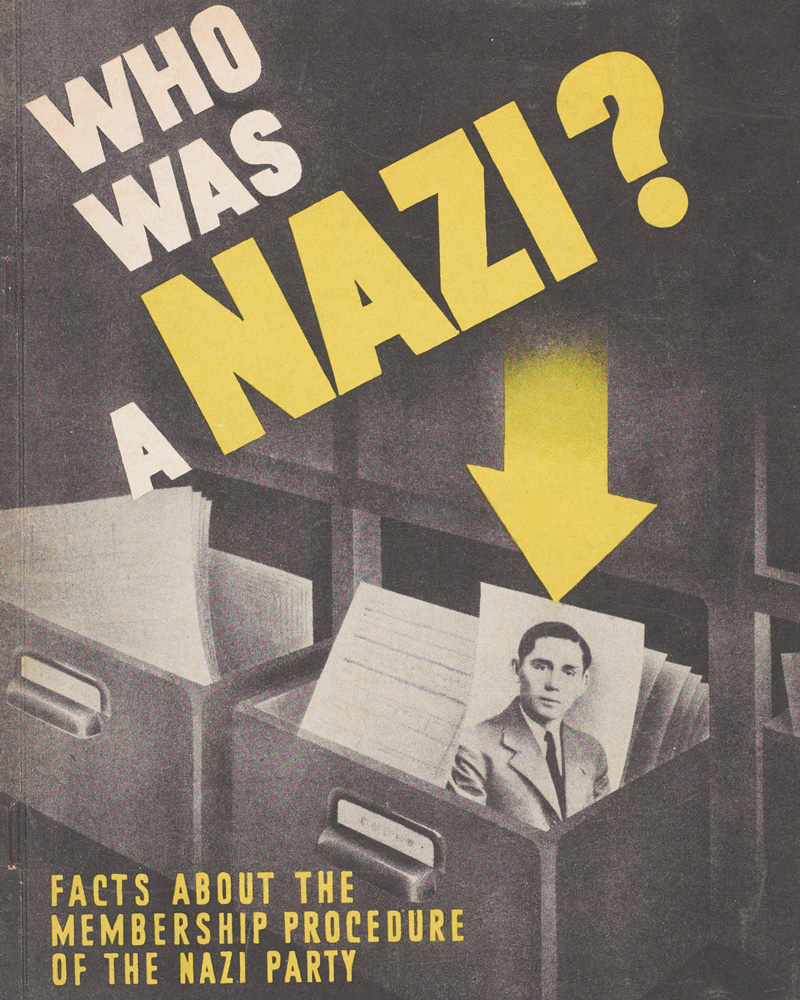

De-nazification

The hunt for war criminals was accompanied by a campaign to rid German and Austrian politics, industry, media, arts, and the judiciary of Nazis. Former party and SS members were removed from positions of power and influence, and Nazi organisations were abolished.

At the same time, hundreds of thousands of Germans were detained in internment camps while their backgrounds were investigated. There were nine such camps in the British zone, all guarded by British troops.

By late 1946, growing tensions with the Soviet Union, the economic importance of western Germany and a lack of Allied manpower to run the de-nazification effort, saw the campaign wind down. In their zone, the British handed over de-nazification panels to German authorities.

A ruined nation

The BAOR and Control Commission Germany also had to restart German economic life. Years of bombing and the recent fighting had left agriculture, industry and transport in ruins. Industrial output was down by a third from 1939 levels. There were shortages of food, clothes and fuel. Millions of people had been made homeless by the war.

In 1945-46, the British mobilised released German prisoners of war to assist in gathering the harvest (Operation Barleycorn) and to work in the Ruhr coal mines (Operation Coalscuttle). But this only provided limited assistance. For most Germans, life in the immediate post-war years was one of rationing, shortages and poverty.

‘I shall never forget that experience of entering Hamburg... as far as the eye could see it was just devastation. What had obviously once been lovely buildings were now just ruins, shattered walls, great tumbles of stone, and a population seemingly staggering about like tired zombies. I remember the stench, too, as hundreds of bodies remained, still awaiting burial.’Corporal Albert Winstanley, Royal Army Medical Corps — 1946

Economic recovery

Initially, there was a reluctance among the wartime Allies about fully rebuilding the German economy. Some planners argued that Germany should be reconstructed purely as an agrarian state, one that lacked the heavy industry needed to wage a future war.

The victorious powers also seized German military, technological, industrial and scientific assets, as well as all patents in Germany. Many factories and laboratories were dismantled and shipped off as a form of reparations.

Eventually, however, the realisation that the economic recovery of Europe was largely dependent on the rebirth of German industry changed the minds of the Americans and British. They also feared the possibility of civil unrest developing, with an accompanying upsurge in Communist influence, if Germans' living standards did not improve.

This change in policy was exemplified by the introduction of the Deutsche Mark (DM) in 1948, which replaced the weak wartime currency, the Reichsmark (RM). This brought an end to the black market, helped stop inflation and stabilised the economic recovery.

In 1949, Marshall Aid was extended to the newly formed West Germany. This American package of economic and technical assistance boosted industry and raised living standards.

Demobilised German soldiers boarding lorries to be taken to reconstruction projects, June 1945 (© IWM (BU 7620))

Army's rebuilding role

Germany's economic rebirth was assisted by the British Army. Major Ivan Hirst and his comrades of the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers took over the Volkswagen plant in Wolfsburg in 1945, initially to make and repair cars for the British. The CCG provided raw materials and labour.

Eventually, Hirst helped turn Volkswagen into today's well-known brand. Most of the factory's workforce initially consisted of displaced persons from across Europe, but more Germans were employed as time went on. By the end of 1947, 20,0000 cars had been made.

Other German businesses were assisted by the Army, including the KWS Grain Factory and the Huth-Apparatebau radio factory in Hanover. The latter concern employed locals to make radio sets manufactured primarily from components salvaged from German military equipment.

The British Army also helped found 'Der Spiegel' magazine. The latter was co-founded in Hanover by Major John Chaloner who was assigned to the Public Relations and Information Services Control, a unit rebuilding the German media industry under the supervision of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office. He worked with recently released German prisoner of war Rudolf Augstein.

The BAOR also mobilised former enemy soldiers into the German Civil Labour Organisation (GCLO). This provided paid work and accommodation for thousands of men. By late 1947, over 50,0000 Germans were employed as labourers, drivers, mechanics and in many other roles. In 1948-49, the GCLO played a major part in supporting the Allied effort during the Berlin Airlift.

A civilian worker at the Huth-Apparatebau factory, Hanover, 1946 (© IWM (BU 12375))

Reconstruction

Field Marshal Sir Gerald Templer served as Director of Military Government in the British occupation zone after the war. In this British Army training film, he explains the motivations for the reconstruction of western Germany.

‘I had two civilian suits made while in Germany. It was all on the black market. It was stuff we sold that we shouldn’t have, but that was the way of life… Cigarettes were terribly short in Germany and their tobacco was awful, so they liked English cigarettes. For 200 cigarettes you could get a suit. There was nothing in the German shops at all. It was all black market.’Private Bernard Tamplin — 1947

Black market

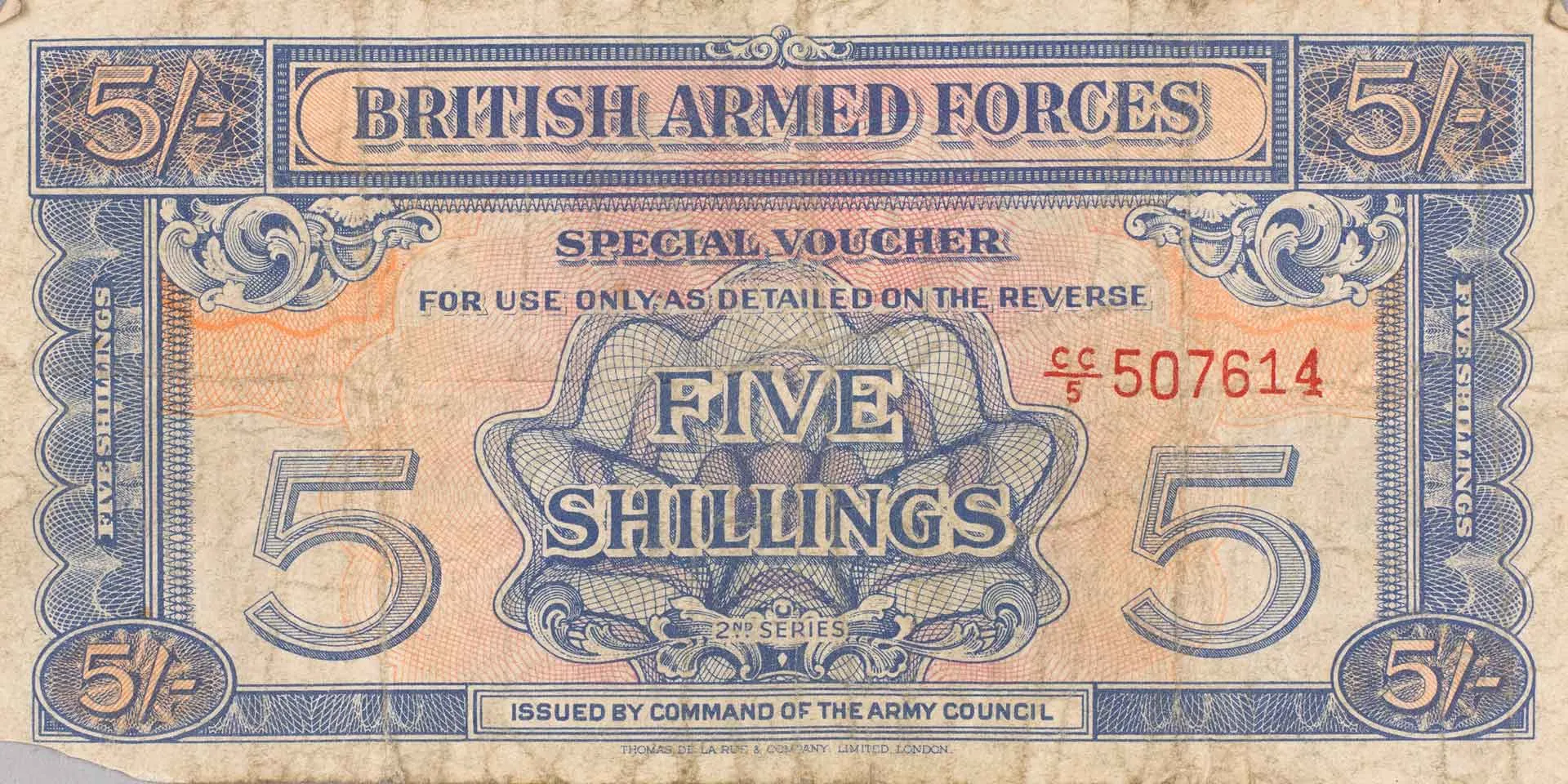

The shortage of food and other supplies immediately after the German surrender meant that illegal commerce, the so-called ‘black market’, filled the void. The wartime Reichsmark (RM) was almost worthless, so goods like cigarettes and coffee served as makeshift currency. Many goods were supplied to illegal traders by Allied servicemen.

British soldiers often bought goods cheaply in staff canteens and NAAFI shops, which were reserved for their use only, and sold them on the black market for RMs. Initially, RMs were accepted in Army canteens and stores and could be used to buy more goods, or converted into sterling and sent home as money orders. For example, a packet of NAAFI-issued cigarettes, which cost 1-2 shillings (5-10p), could be sold for 160RM on the black market, worth £4 at the official rate of exchange of 40RM to £1.

The CCG tried to stamp out the black market by investigating suspects, raiding markets and checking traffic at road blocks. In February 1948 alone, over 4,200 people were arrested for black market activities in the British zone.

From 1946, military involvement in the trade was partly curtailed by issuing troops with British Armed Forces Special Vouchers. This meant they had a different currency from the locals, and the only one accepted in NAAFI canteens and various messes.

But the wider black market was only fully ended by West Germany’s economic recovery and by issuing a stable and trusted new currency, the Deutsche Mark (DM).

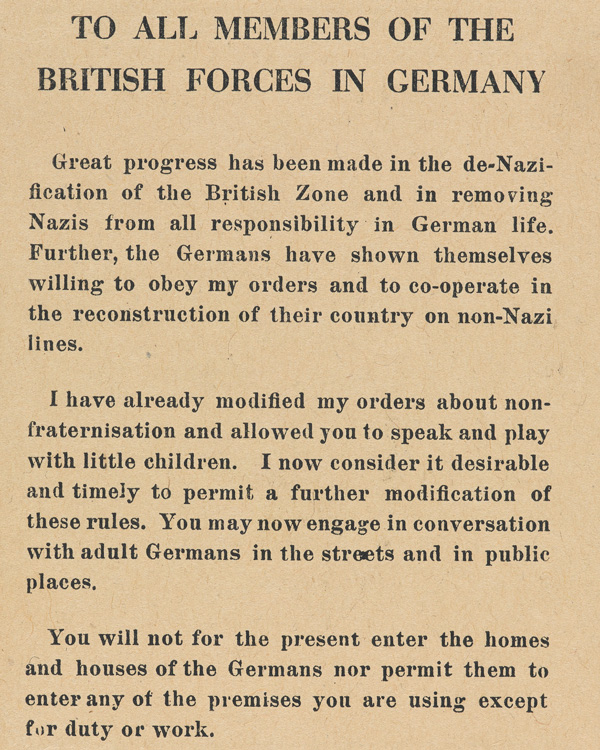

Non-fraternisation

From the Army's first crossing into enemy territory, personnel were expressly forbidden to have any social contact with Germans. In March 1945, Field Marshal Montgomery sent a letter outlining the policy to all soldiers in 21st Army Group. Its main focus was on enforcing a sense of defeat on the Germans:

‘Twenty-seven years ago the Allies occupied Germany: but Germany has been at war ever since. Our Army took no revenge in 1918; it was more than considerate… So accommodating were the occupying forces that the Germans came to believe that we would never fight them again in any cause. From that moment to this their continued aggression has brought misery to millions.’

‘You have a positive part in winning the peace by a definite code of behaviour. In streets, houses, cafes, cinemas etc, you must keep clear of Germans, man, woman and child, unless you meet them in the cause of duty. You must not walk out with them, or shake hands, or visit their homes, or make them gifts, or take gifts from them... In short, you must not fraternise with Germans at all.’Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery — March 1945

Policy change

But this policy proved unenforceable. Soldiers of all ranks resisted the ban on fraternisation. Many had to work with Germans to re-establish industrial concerns and local government, making it impossible to adhere to the policy's strict conditions.

Others actively sought out the company of German women, or worked closely with civilians in the black market, while some just felt pity for a poor and desperate people.

Eventually, the High Command accepted the policy was unworkable. In June 1945, soldiers were no longer forbidden from fraternising with children. The following month, they were authorised to hold conversations with adult Germans in public.

Finally, in September 1945, Montgomery cancelled his previous orders on the issue and simply reminded his soldiers that they were 'to conduct themselves with dignity, and to use common sense when dealing with Germans'.

Even so, he still banned his troops from billeting with German families, or from marrying Germans. But as time went on, these rules too were quietly forgotten.

The relaxation of fraternisation rules in Herford, July 1945 (© IWM (BU 8900))

Displaced persons

At the end of the war, the Allies also had to deal with millions of displaced persons (DPs). These included former concentration camp inmates, forced labourers taken from their homelands by the Nazis to work in Germany, and Allied prisoners of war (POWs) who had to be sent home.

The military in the various zones of Germany did what they could for DPs, many of whom were sick or malnourished. They were housed in makeshift camps where they were fed, medically checked and processed. But eventually, in October 1945, the Allies and Soviets handed responsibility for DPs to the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) .

In the British zone, the Army assisted UNRRA by providing transportation, supplies and security. Dealing with so many people took time. But by the end of 1945, over six million refugees had been repatriated by the military of the four occupied zones and UNRRA. The last German DP camps closed in the early 1950s.

Exiles

Many displaced persons who were former residents of the Soviet Union, or from nations in Eastern Europe and the Balkans recently taken over by Communists, had no wish to return. Some had collaborated with the Germans and could expect little mercy. But even those forcibly taken by the Germans would still be suspects in the eyes of the Communist authorities.

Political opponents of the Communists also feared going home. Indeed, many of those who did return were jailed or executed in countries like Poland and Yugoslavia.

The British, in their zone of occupation, formed some of these people into the Civil Mixed Watchman Service. They were tasked with guard duties in the camps set up to deal with the tide of humanity moving through Germany. The British also established the Civilian Mixed Labour Organisation to undertake reconstruction work.

In 1959, both organisations were merged into the Mixed Service Organisation (MSO), which would continue to work for the BAOR for many years. MSO units had a British Army commanding officer and senior non-commissioned officers overseeing a multi-national rank and file.

German refugees

The western Allies also had to assist millions of German refugees. Many were from Germany's eastern provinces and had fled the vengeful Red Army, or were ethnic Germans forcibly expelled from countries like Poland and Czechoslovakia. Their numbers were swelled by thousands of German POWs returning from abroad.

Due to its location on the Baltic, the British zone received a great number of German refugees who had come by sea. This made the accommodation shortage even worse and also caused a reduction in the food ration in early 1946.

Eventually, most German refugees obtained accommodation and work as the economy recovered. Those Germans who had been expelled from Eastern European countries were assimilated by being granted German citizenship.

Disagreements

While the British got on with administering their zone, relations with the Soviet Union within the Allied Control Council gradually declined. The British, Americans and French were unable to come to an agreement with the Soviets about war reparations, the status of ethnic German refugees and the overall future of Germany.

In western Germany, the British and Americans unified their zones in 1947 so as to better co-operate politically and economically. The French joined them the following year. Meanwhile, in eastern Germany, the Soviets set about establishing a Communist political and economic system.

Iron curtain

These developments occurred against a backdrop of rising tensions between the Western Allies and Soviets elsewhere in Europe. Potential flashpoints included the threat of a Communist takeover in Greece, and growing Soviet demands for territorial concessions from Turkey.

In a speech in March 1946, less than a year after the war’s end, Winston Churchill denounced the Soviet imposition of Communism on the nations of Eastern Europe. His words came to define much of the post-war era: 'From Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic, an iron curtain has descended across the Continent.'

US President Harry Truman’s intention to support any nations threatened by Communism (the so-called Truman Doctrine of 1947) raised the stakes even higher.

In March 1948, the Soviet Union withdrew from the Allied Control Council after learning of Allied proposals to create a new West German state. There was now a growing concern in the West that the Soviets would attempt to impose by force their solution to the German question.

Troops arrive at RAF Gatow to reinforce the British garrison, Berlin Blockade, 1949 (© IWM (BER 49-144-002))

Berlin

The total breakdown of Soviet-Allied cooperation and joint administration in Germany became apparent with the Berlin Blockade in 1948-49. The Soviets, taking advantage of their zone's position surrounding the German capital, severed road and rail links between western Germany and Berlin.

The Western Allies responded by airlifting supplies to the people of West Berlin. The Allies were so alarmed by the Soviet actions that they decided the only answer was collective defence. The North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (Nato) was therefore formed in April 1949 with General Dwight Eisenhower as the first Supreme Allied Commander Europe.

Engineers building a Bailey Bridge in West Berlin to aid the movement of supplies, 1949 (© IWM (BER 49-161-027))

Two German states

In May 1949, the three western occupation zones were merged to form the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany). The Soviets followed suit in October 1949 with the establishment of the German Democratic Republic (East Germany).

In the west, the three post-war occupation zones were formally abolished by treaty in May 1955. That same month, West Germany joined Nato. It was also encouraged to build a new military, the Bundeswehr, which took its place alongside the BAOR as an ally in the burgeoning Cold War.

In response to West Germany joining Nato, the Communist states of Eastern Europe formed the Warsaw Pact under Soviet tutelage.

As a result of its commitments to Nato, Britain had to convert the BAOR from a static occupation force consisting of two divisions into a field force of at least four divisions. This force's main focus now changed to preparing to face an invasion of West Germany by the Warsaw Pact.