SOE agents with a Maquis group near Savournon, Hautes-Alpe, August 1944 (© IWM (HU 57107))

Setting Europe ablaze

In June 1940, a new volunteer force, the Special Operations Executive (SOE), was set up to wage a secret war. Its agents were mainly tasked with sabotage and subversion behind enemy lines. They had an influential supporter in Prime Minister Winston Churchill, who famously ordered them to 'set Europe ablaze!'

The SOE's director of operations was Brigadier Colin Gubbins, a Commando officer whose interest in irregular warfare originated from his service during the Irish War of Independence (1919-21). Gubbins had also been involved in planning a sabotage force to work behind the lines in the event of a successful German invasion of Britain.

Sabotage

Gubbins’s approach to warfare included blowing up trains, bridges and factories, as well as fostering revolt and guerrilla warfare in enemy-occupied countries.

After completing a gruelling training regime, SOE agents were parachuted into occupied Europe and eastern Asia to work with resistance movements. Many were serving soldiers, often with commando training, but others joined directly from civilian life.

Women also joined up. Some were enlisted in the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry (FANY) to disguise their secret work. They were the only women permitted a combat role during the Second World War.

Quiz

What was the average life expectancy of an SOE wireless operator in occupied France?

Unlike other special forces, SOE operatives usually wore civilian clothes. This meant they could expect to be shot as spies if captured. They also risked torture by German Gestapo operatives trying to extract information.

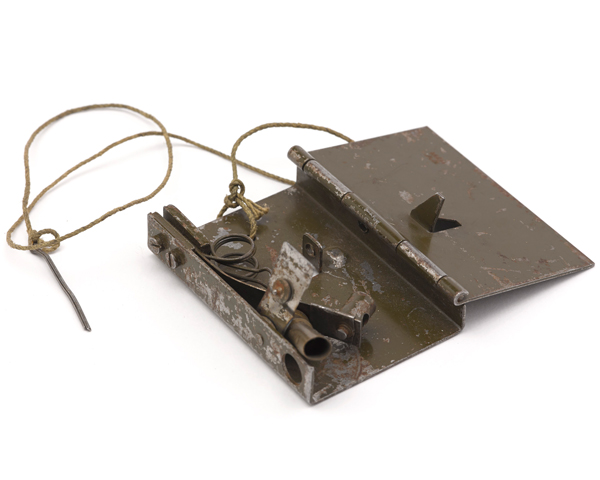

Special weapons

SOE operatives were often parachuted in with clandestine radio transmitters disguised to look like ordinary suitcases. They were also equipped with specially designed explosives, silenced guns and forged papers.

Research and development stations were set up near Welwyn in Hertfordshire, where scientists and technicians worked on specialist weapons, sabotage equipment and camouflage materials.

Official obstruction

The Secret Intelligence Service (SIS) - now known as MI6 - viewed the SOE with suspicion. Its head, Sir Stewart Menzies, argued that SOE agents were 'amateur, dangerous and bogus'. He brought massive internal political pressure to bear on the fledgling organisation.

The SIS did not want the SOE disrupting their agents' intelligence-gathering operations by blowing up bridges and factories. Similarly, Bomber Command resented having to loan aircraft for SOE missions. They wanted to win the war by bombing Germany to its knees. But with Churchill as their ally, the SOE - like many other wartime special forces - survived and flourished.

Michael Trotobas

A typical agent was Michael Trotobas. Half French, he was recruited to the SOE’s French Section after escaping from Dunkirk (1940) and given a commission in the Manchester Regiment. In 1941, he was parachuted into the Chateauroux area under the code name 'Sylvestre'.

Six weeks later, he was arrested with nine other agents. However, the following year, he took part in a mass escape from Mauzac prison, going on to establish and lead the Lille-based 'Farmer' circuit.

From 1943, Trotobas successfully led a sabotage campaign, targeting the Lans-Béthune railway, tool factories at Armentières, and naval depots at Boulogne and Calais. In June 1943, his group damaged the Lilles-Fives locomotive works.

Trotobas was killed in November 1943, while trying to evade arrest after the Germans extracted the address of his safe house from a captured agent.

He was recommended for a posthumous Victoria Cross, but this was rejected as no senior rank had been present to witness his bravery. This was a common outcome for special forces personnel.

Violette Szabo

Violette Szabo grew up in London. She had a French mother and an English father. Following the death of her French husband at the Battle of El Alamein in 1942, she joined the Auxiliary Territorial Service. Her French background made her an ideal recruit for SOE’s French Section and she was enlisted in the FANY as cover.

After training, Violette was parachuted into occupied France with her suitcase transmitter and fake papers, joining the 'Salesman' circuit in April 1944. When this group was exposed by the Germans, she was forced to return by plane to Britain.

During the D-Day landings she returned to France, parachuting into Limoges on 8 June 1944. She assisted the resistance in sabotaging German lines of communication. This included helping delay the deployment of the 2nd SS Panzer Division to Normandy.

Violette was captured on 10 June. Following her interrogation and torture she was sent to Ravensbruck concentration camp where she was executed in February 1945.

In December 1947, her five-year-old daughter Tania received the George Cross from King George VI on her mother's behalf.

Raids

The men and women of the SOE carried out many other famous operations, including the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich - Deputy Chief of the Schutzstaffel (SS) - in Czechoslovakia during 1942.

In 1943, SOE parachutists also took part in the destruction of the heavy water plant at Vemork in Norway, which delayed the Nazis’ atomic bomb programme.

Jedburgh

One of the SOE’s most important missions was Operation Jedburgh. Working with Americans from the Office of Strategic Services, its agents parachuted into France immediately before the D-Day landings and during the subsequent months. Its three-man teams led local resistance forces in actions that delayed German troop deployments to Normandy.

Jedburgh agents and the resistance successfully held up the movements of the 2nd SS Panzer Division. They siphoned off the axle oil from the division's rail transport cars, replacing it with abrasive grease that seized them up. Had this elite armoured force reached Normandy prior to the Allied breakout, it would have wreaked havoc.

During the subsequent campaign in Belgium and Holland, the teams continued to provide an essential link between resistance groups and the Allied command.

'The disruption of enemy rail communications, the harassing of German road moves and the continual and increasing strain placed on German security services throughout occupied Europe… played a very considerable part in our complete and final victory.'General Dwight Eisenhower, Supreme Allied Commander — May 1945

Partisans

In late 1941, Britain recognised Dragoljub Mihailovic's Serbian 'Chetniks' as the official resistance in Yugoslavia. SOE agents were sent to assist them in their fight against the Axis occupiers.

The 'Chetniks', however, soon became involved in a civil war against a rival resistance movement, the 'Partisans', led by Josip Broz, or 'Tito'. This force was communist, multi-ethnic and opposed to Mihailovic's Royalist movement. Growing 'Chetnik' collaboration with the Axis against Tito resulted in Britain switching its support to the 'Partisans' in December 1943.

From then on, SOE agents - often assisted by Commandos, the Special Boat Service and the Special Air Service - all fought alongside the Yugoslav resistance.

They undertook raids against Axis military installations and engaged in acts of sabotage. Together, they forced the Axis to garrison Yugoslavia with hundreds of thousands of soldiers, preventing their use on other war fronts.

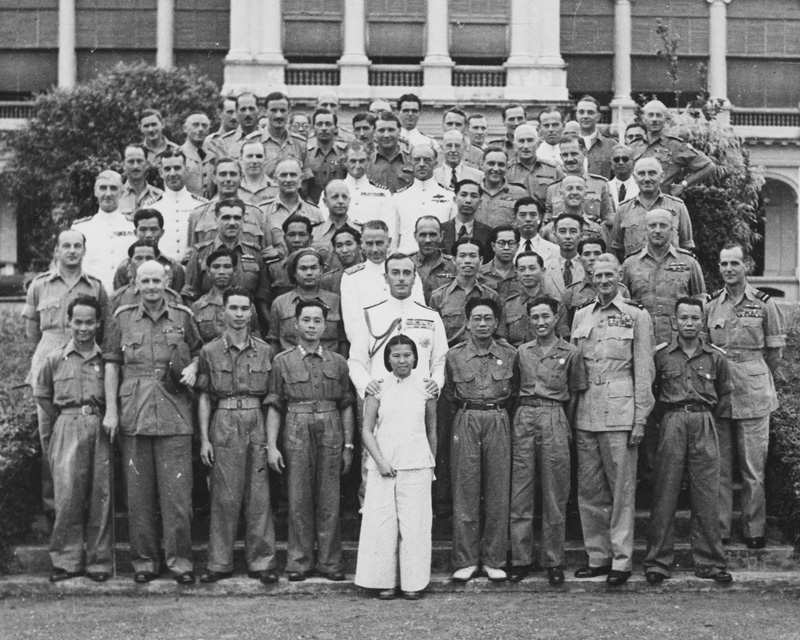

Force 136

In eastern Asia, the SOE established Force 136 to liaise with resistance groups in Japanese-occupied countries. Commanded by British officers, it recruited indigenous people in Burma (now Myanmar), Malaya (now Malaysia), China and Thailand to assist in sabotage and intelligence gathering.

This sometimes had unforeseen circumstances. In Malaya, Force 136 collaborated closely with the Malayan Peoples' Anti-Japanese Army (MPAJA). This was dominated by Chinese communists who went on to play a leading role in the Malayan Emergency (1948-60).

Disbanded in December 1945, the MPAJA was supposed to hand in its Allied-supplied weaponry to the British. But much remained hidden and was used by the communists in their subsequent guerrilla campaign.

Reprisals

SOE operations often relied on resistance support or help from local people. This sometimes led to brutal reprisals against civilian populations.

After the killing of Reinhard Heydrich in 1942, the SS murdered 5,000 men, women and children in two villages near Prague.

In June 1944, the 2nd SS Panzer Division massacred 642 French civilians in the village of Oradour-sur-Glane, angry at being harassed and delayed by SOE operatives and the resistance.

Disbandment

The SOE came under increasing pressure after its main supporter, Winston Churchill, was defeated in the 1945 general election. It also faced renewed opposition from the SIS and others in Whitehall who wanted control of British intelligence services and operations.

The SOE was abolished in January 1946. The SIS absorbed much of its training and research staff.