Centres of revolt

Following the outbreak of the Indian Rebellion at Meerut in May 1857, uprisings occurred across northern and central India. The main centres of revolt were Delhi, Cawnpore (now Kanpur), Lucknow, Jhansi and Gwalior.

For over a year, the British struggled to retain their rule during a bloody and often cruel campaign that witnessed atrocities by both sides.

Delhi

The city of Delhi became the centre of the uprising. It was the seat of Bahadur Shah Zafar, the old and largely powerless Mughal emperor. The mutineers from Meerut had immediately gone there to ask for his support and leadership, which he reluctantly gave.

Delhi occupied a key strategic position between Calcutta (now Kolkata) and the new territories of the Punjab. Its recapture was a priority for the British.

11 May 1857

Aided by a mob from the Delhi bazaar, the rebels killed Europeans and Indian Christians.

7 June 1857

A hastily raised force of 4,000 men succeeded in occupying a ridge overlooking Delhi, but was too weak to succeed in retaking the city.

July-August 1857

Faced by over 30,000 mutineers, the British came under increasing pressure. The army began to suffer losses through cholera. In searing heat, the British held off repeated rebel efforts to take the ridge.

14 August 1857

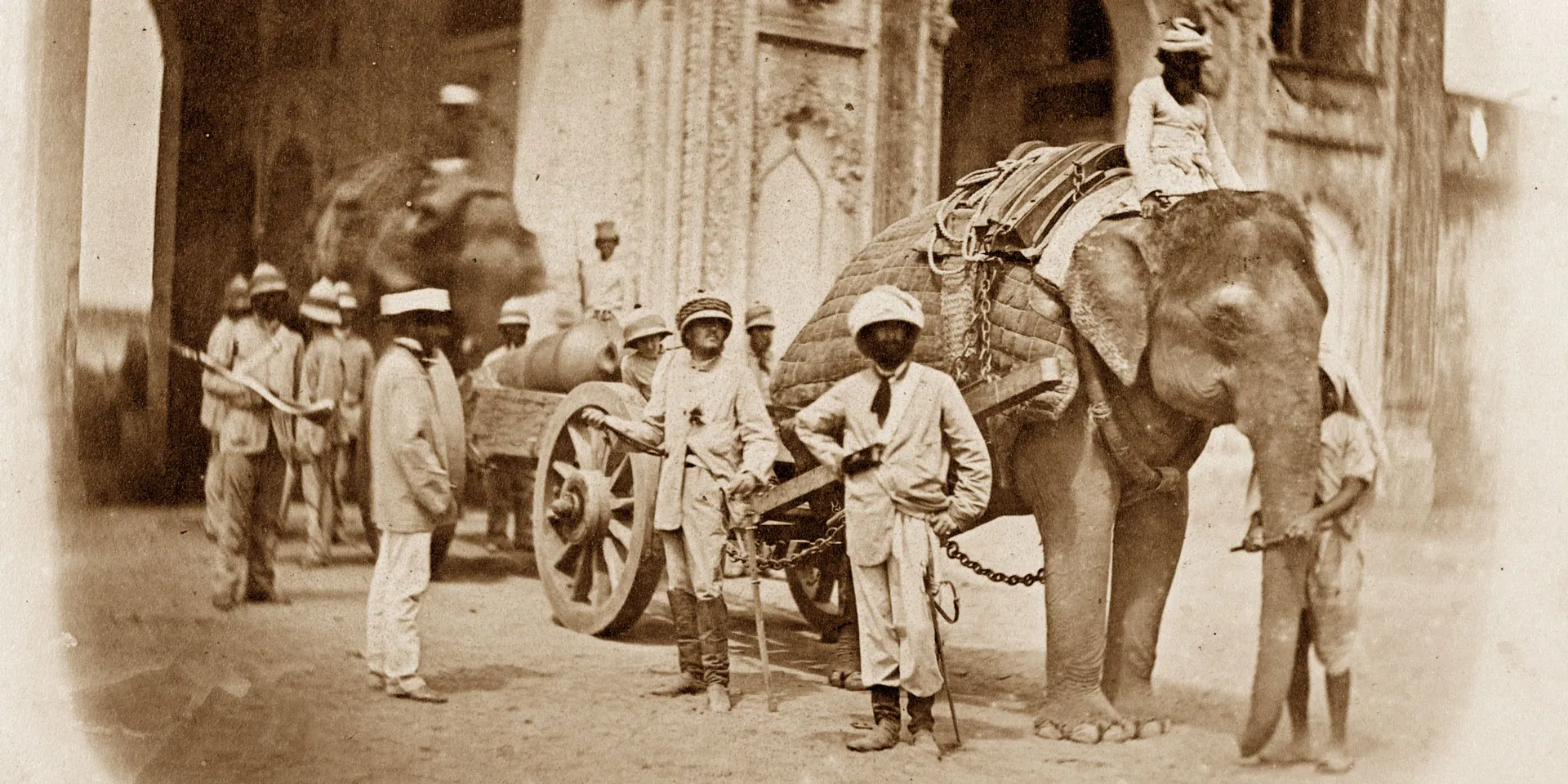

Reinforcements arrived from the Punjab, including a siege train of 32 guns and 2,000 men under Brigadier-General John Nicholson. En route, Nicholson had executed without trial hundreds of mutineers and innocent civilians.

14 September 1857

By September, the British had 9,000 men before Delhi. A third were British, the rest were Sikhs, Punjabi Muslims and Gurkhas. Their assault began when artillery breached the walls and blew in the Kashmir Gate.

14-21 September 1857

After a week of vicious street fighting, Delhi was taken. It was then ransacked in an orgy of looting and killing. The city’s recapture proved the decisive factor in the suppression of the revolt.

Cawnpore

Cawnpore was a major crossing point on the River Ganges, and an important junction, where the Grand Trunk Road and the road from Jhansi to Lucknow crossed. In June 1857 the sepoys there rebelled and laid siege to Major-General Sir Hugh Wheeler’s garrison.

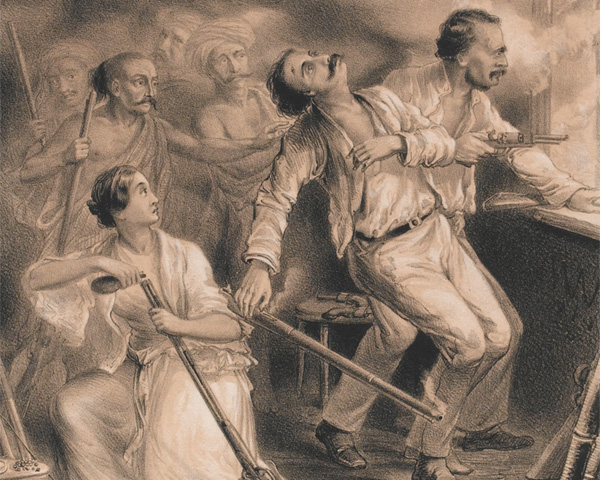

Wheeler had retreated to an entrenchment outside the city. Nana Sahib, a local ruler who had suffered from the British seizure of his estate, led the rebels. For nearly three weeks, under constant fire and a burning sun, 1,000 Britons awaited rescue.

25 June 1857

Nana Sahib learnt that a British relief force was approaching Cawnpore and offered Wheeler’s garrison safe passage downstream to Allahabad (now Prayagraj). The British boarded waiting boats and were then fired upon. Any men who survived the ambush were immediately killed.

15 July 1857

The surviving 120 women and children were imprisoned. When it was heard that the British were near, the prisoners were murdered and their bodies thrown down a well.

16 July 1857

Major-General Sir Henry Havelock's relief force reached Cawnpore a day later. After carrying out indiscriminate reprisals against both the guilty and innocent, Havelock marched northwards towards Lucknow, but was forced to turn back.

November 1857

Cawnpore was held from July until November, when Lieutenant-General Sir Colin Campbell marched most of its garrison to Lucknow. He left behind a small detachment under Brigadier Charles Windham.

26 November 1857

Nana Sahib's general, Tantya Tope, had gathered an army to recapture the city. On 26 November, Windham drove off Tantya's advance guard, but was forced back to Wheeler's old lines. Campbell then returned from Lucknow and found Windham surrounded and Cawnpore in rebel hands.

6 December 1857

Windham's opening bombardment deceived the rebels that Campbell was about to attack their left. His real attack was made on the right. Campbell's heavy naval guns were the decisive factor. As Tantya’s troops broke and fled, Nana Sahib's men were defeated north of the city.

'The place was literally running ankle deep in blood, ladies' hair torn from their heads was lying about the floor; poor little children's shoes lying here and there, gowns, frocks and bonnets belonging to these poor creatures scattered everywhere. But to crown all horrors, after they had been killed, and even some alive, all were thrown down a deep well in the compound. I looked down and saw them lying in heaps. I very much fear there are some of my friends included in this most atrocious fiendish of murders.’Major George Bingham at Cawnpore — 1857

The Devil's Wind

The Cawnpore massacre inflamed British feelings. They left the site untouched as a reminder to newly arrived troops. News of the atrocity, and others like it elsewhere, installed a desire for revenge.

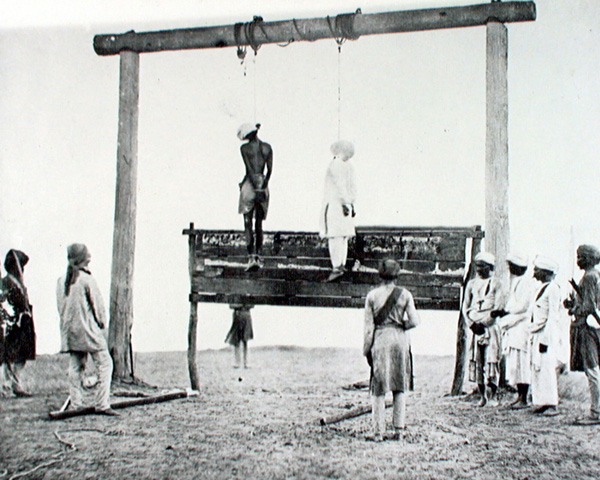

In the early months of the British recovery, few mutineers were captured alive. Thousands were indiscriminately hanged and many innocent civilians killed.

When trials were held, those convicted of mutiny were blown from cannon. It was a cruel punishment with a religious dimension. By blowing the body to pieces the victim lost hope of entering paradise. The people of northern India called the long period of reprisals ‘the Devil’s Wind’.

Situation in Oudh

When news of the rising reached Sir Henry Lawrence, the Chief Commissioner of Oudh, he fortified his Lucknow Residency, and stockpiled supplies, ready for a siege.

Lucknow was the capital of Oudh, a state annexed the year before in a move that had caused great resentment. The sepoys rebelled on 30 May 1857 and this was followed by riots in the city.

30 June 1857

Lawrence’s initial expedition against the rebels at Chinhut was defeated and his men retreated in disorder. The rebels now besieged the Lucknow Residency. Lawrence had about 1,600 troops - half of them loyal sepoys - to defend the compound, and a similar number of civilians to protect.

4 July 1857

Lawrence was killed when a shell exploded in his room. Command passed to Colonel John Inglis of the 32nd Regiment.

26 September 1857

A relief force of 2,500 soldiers under Major-General Sir Henry Havelock left Cawnpore and fought its way into Lucknow. But, after sustaining heavy casualties, it was too weak to evacuate the defenders.

16 November 1857

Sir Colin Campbell’s relief force of 4,500 men arrived. They stormed the Secundra Bagh, a walled enclosure that barred the way to the Residency. The British artillery opened a breach and the infantry stormed inside. In fierce fighting, they killed around 2,500 rebels.

22 November 1857

Campbell was finally able to evacuate the Residency. He left behind a small garrison under Sir James Outram at the Alumbagh, a large enclosure outside the city, to stop the rebels undertaking offensive operations.

1 March 1858

Campbell returned to Lucknow and his reinforced army joined Outram’s 4,000 men.

5 March 1858

Campbell attacked Lucknow in set-piece fashion, moving forward from position to position, after his engineers had constructed bridges across the River Gumti. Over the following days, his gunners blasted their way through the city’s buildings, while the infantry engaged in bitter hand-to-hand fighting.

14 March 1858

The Nawab of Oudh's palace was captured and looted, but many of its defenders escaped into the countryside to fight on. Two days later, the Residency was secured and Campbell beat off counter-attacks on the Alumbagh and his positions north of the Gumti.

'Inch by inch they were forced back to the pavilion... where they were all shot or bayoneted. There they lay in a heap as high as my head, a heaving mass of dead and dying inextricably entangled. It was a sickening site, one of those which even in the excitement of battle and the flush of victory, make one feel strongly what a horrible side there is to war. The wounded could not get clear of their dead comrades, however great their struggles... and vented their rage and determination on every British officer who approached, by showering upon him abuse of the foulest description.'Field Marshal Lord Roberts recalling the assault on Secundra Bagh — 1897

Central India

Resistance to British control of central India centred on Jhansi, where Rani Lakshmi Bai opposed the annexation of her state.

In June 1857, the Bengal Army regiments stationed in central India mutinied. They were joined by the Gwalior Contingent, a force in the service of the pro-British Maharajah Sindia.

On 5 June, British officers, civilians and Indian servants who were taking refuge in the fort at Jhansi, were killed by the Rani’s men. The rebels had offered to spare their lives if they surrendered, and it was believed that the Rani had guaranteed their safety.

December 1857

Major-General Sir Hugh Rose’s Central India Field Force advanced from Bombay.

5 February 1858

Rose relieved Saugor (now Sagar), where a small European garrison was besieged, and then advanced on Jhansi.

24 March 1858

Rose’s army besieged Jhansi before defeating Tantya Tope’s relief force a week later.

3 April 1858

Jhansi was stormed and looted. At least 5,000 defenders died. But, after personally leading a counter-attack, the Rani escaped.

May 1858

Rose then advanced on Kalpi, winning battles at Kunch on 1 May and Kalpi itself on 16 May.

June 1858

The rebels took their remaining forces into Gwalior, hoping to defeat its pro-British ruler. At Morar, east of Gwalior, Sindia's troops defected to the rebels on 1 June.

17 June 1858

Leaving Kalpi, Rose marched through the summer heat to Gwalior. He recaptured Morar and then defeated the rebels at Kotah-ke-Serai on 17 June. The Rani was killed in this action.

19 June 1858

Two days later, the British recaptured Gwalior. Most rebels surrendered or went into hiding. But Tantya managed to evade the British until April 1859, when he was betrayed and then hanged.

Political changes

The rebel defeat in Gwalior effectively ended the rising. The British quickly took steps to prevent any further unrest. The East India Company was abolished and the government of India transferred to the British Crown. A secretary of state for India was appointed and the Crown's viceroy became head of the government.

Bahadur Shah was tried for treason and sentenced to exile in Burma (now Myanmar). He died there in 1862, bringing the Mughal dynasty to an end. In 1877, Queen Victoria was crowned Empress of India in his place.

The British also began to employ higher-caste Indians and rulers in the government. More Indians were recruited to the civil service. The British also stopped taking rulers' lands and no longer interfered with local religious practice.

Coat worn by the Viceroy's heralds at the Delhi assembly that proclaimed Queen Victoria as Empress of India

Military reform

To safeguard British rule, the ratio of European to Indian soldiers was increased. The army was also reorganised so that it needed its British components to function effectively.

Indian soldiers were issued with a rifle that was inferior to that of their British counterparts and given limited logistical support. Control of artillery - crucial to the rising’s outcome - remained in British hands. In effect, the Indian sepoys became auxiliaries to British soldiers.

There were also changes in recruitment. Punjabi Muslims, Sikhs, Gurkhas, Baluchis and Pathans replaced high-caste Hindus from the Ganges Valley, who were no longer trusted owing to their role in the rebellion. It was believed that a more diverse army would be less likely to unite and rebel.